The original Chrysler V8 engines didn’t need a code—they were “the V8.” (Before that, they were simply “the eight,” when the company relied on straight-eights, or inline eight-cylinders).

Chrysler’s first V8 engines had been a technical success and a commercial failure. The engineers used hemispherical heads with dual rockers because they were the most efficient at turning fuel into power; despite Ford’s pre-war success with an inefficient V8, the engineers did not predict that V8 engines would soon be needed to sell their mass-market Plymouths, or that making bigger engines would replace of efficiency. They were driven by their technical skill and research, not by the markets.

It did not take long for Chrysler leaders to realize that hemispherical-head engines were too wide, too slow to make, and too costly. Their first response was switching to “nearly as good” polyspherical-chamber heads in some cars; later, they redesigned the blocks and swapped in wedge-type heads, creating the A engines, which solved the mass production problem and made a V8 small enough to be in the little Valiant.

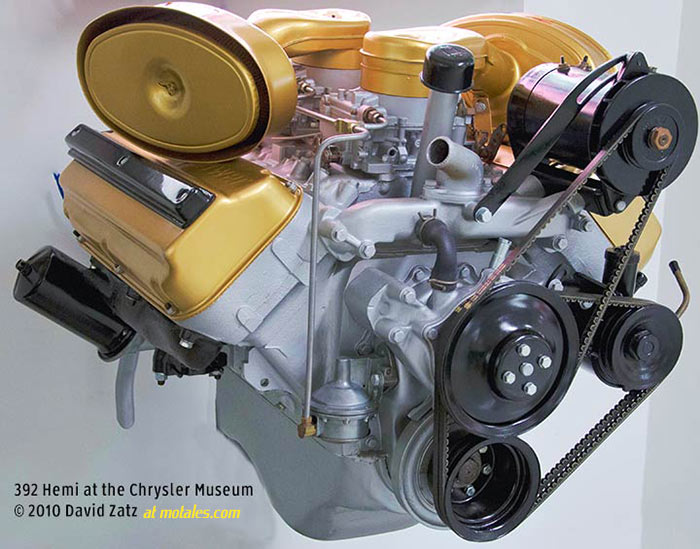

Now there was another problem: size. The first series of V8s maxed out at 392 cubic inches, and something bigger was clearly going to be needed. It was time for a brand new series of engines.

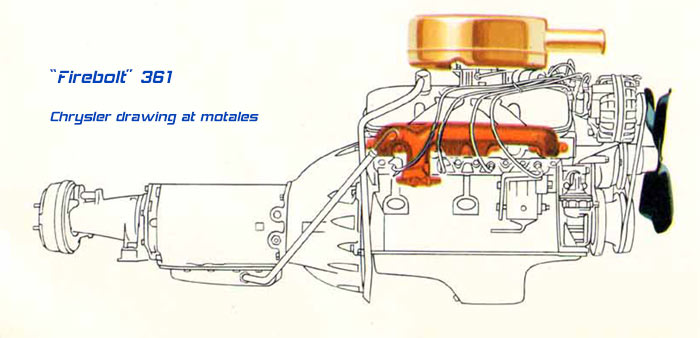

B-engine development was led by Robert S. Rarey, who later lead the creation of the slant six; Rarey had been a test engineer for the Hemi aircraft engine in World War II, and had been a Plymouth engine engineer. Legendary engine designer Willem Weertman wrote in his book Chrysler Engines (SAE), “Rarey rose to the challenge, directing his highly regarded overall engineering acumen to the task, along with his customery personal vigor.”

Unlike the prior V8s, these were made by a corporate engine group, and were shared between brands—no longer would quite similar designs have many different parts depending on what nameplate was on the car. This made a good deal of sense for a company with relatively small sales spread across five brands (Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler, and sometimes Imperial).

Lead designer Fred Shrimton and advance engine design supervisor Ray Latham created a large block, with 4.8 inches between the cylinder centers—the largest of any engine ever made by Chrysler—to support larger bores in the future. A deep skirt went three inches below the crank centerline, for stiffness under heavy loads. In case longer strokes would be needed, the team decided on two different versions—one with a 9.98 inch high top deck, and one with a 10.725 inch top deck; the first would have a 3.38-inch stroke, and the second would have a 3.75-inch stroke. The two variations were dubbed B (technically, LB, for low B) and RB (Raised B.) Eventually, the Trenton Engine plant would build four B and four RB engines (not all at the same time, though; they would make two B engines and up to three RB engines at once).

| 350 | 361 | 383 | 400 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bore | 4.06 | 4.12 | 4.25 | 4.34 |

The team chose wedge heads, as they had with the A engines; in this, they were not just copying Chevrolet. The engineers had returned to their labs and found out that the two designs had nearly the same performance in this application; but the wedge chambers, with in-line valves, were lighter, more compact, and cheaper to make than either the Poly or Hemi, with their divergent valves. The slight added performance was not worth the cost in money or weight for production cars—though, eventually, it would be needed for racing.

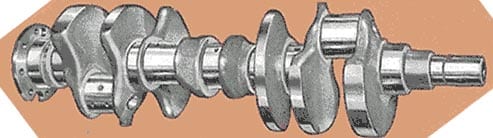

The B engines were developed quickly—Rarey started after 1955, and the engines were ready in late 1957 for the 1958 cars (almost immediately, the team pivoted to creating the slant six). Still, they designed in many clever features, including a horizontal roof in the water jacket to avoid steam pockets; below that was the antifreeze, and above it was oil from the valve rockers, which could flow into the tappet chamber and then the sump. To cut weight, they used short exhaust ports (so the exhaust manifolds were close to the heads), side-by-side intake ports, and a single embossed sheet-metal gasket to seal the joints between the heads and intake. Planning ahead for larger bores and greater power, they went from 10 to 17 bolts to attach the heads; they also used drop-forged steel connecting rods and a forged crank.

Rarey’s team moved the oil pump and distributor from the left/rear (where it was on the Hemi) to the front bottom left of the block, and put the distributor on the front top right. The goal was to move the distributor away from the ventilation equipment at the firewall, and to use shaped oil pan sumps to clear the tie rods (the pump’s aluminum cover was also the oil filter mount). New stamped steel rocker arms replaced the machined arms, saving time and money—though it relied on a supplier to do the research and tool up in time.

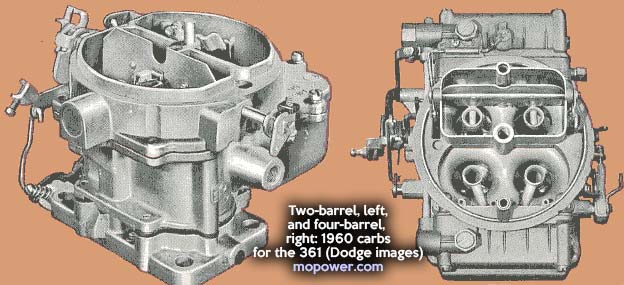

The 1958 B-engines were made in two versions, at 350 and 361 cubic inch versions (the 350 would be fine for winning bets with Chevy people). The 350 was a single-year engine, while the 361 would be made for many years, for trucks and motor homes. Both had relatively large bores and short strokes, with 10:1 compression. DeSoto had two-barrel and four-barrel versions, while Plymouth added had a uniquely-cammed dual-four-barrel 361 which powered the aptly-named Plymouth Fury.

DeSoto sold a two-barrel 350 which was rated at 280 horsepower and 380 pound-feet of torque. To achieve roughly that much power, the 1957 Plymouth Fury’s 318 cubic inch A-engine had needed twin four-barrel carburetors. The B-engine had a clear advantage; the Plymouth 350 four-barrel generated 305 horsepower, the DeSoto Turboflash produced 295, and the Dodge D-500 made 320. Meanwhile, the 361 produced 305 horsepower and 400 pound-feet of torque with a four-barrel carburetor.

Chrysler offered an optional Bendix electronic fuel injection system for the 350 and 361, too; it was incredibly advanced but materials technology could not support the system, and Chrysler ended up swapping in carburetors on nearly all of them (one or two were rebuilt, and work well). These 1958 systems were remarkably similar to the factory systems of the 1980s.

The engines were identical, but each brand gave them unique names. Plymouth used Golden Commando and, later, Sonoramic Commando; Dodge chose Super Red Ram and D-500, confusingly re-using old Hemi names; in 1959, DeSoto belatedly went with TurboFlash. The names were sometimes put onto the valve covers, sometimes not.

As with other Chrysler engines, trucks were beefed up with induction-hardened crankshaft journals, hydraulic valve lifters, rotating sodium-filled exhaust valves, a chrome-alloy cast-iron block, and special rod bearings.

It took very little time—one year—for Chrysler to design its most common performance engine of the 1960s: the 383, a bored-out 361; the higher bore made space for 2.08-inch intake valves. Cam timing was the same as the 1958 350 and 361 (except for the Fury). The 383’s two-barrel carburetor provided 305 horsepower and 410 pound-feet (nearly identical to the 361) while its four-barrel provided 320 horsepower on the Dodge and 325 horsepower on the DeSoto Fireflight.

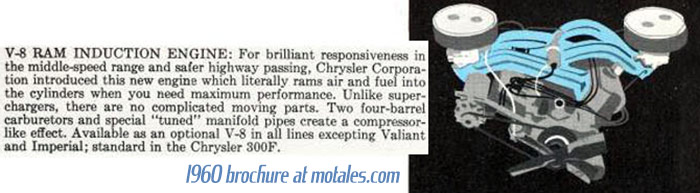

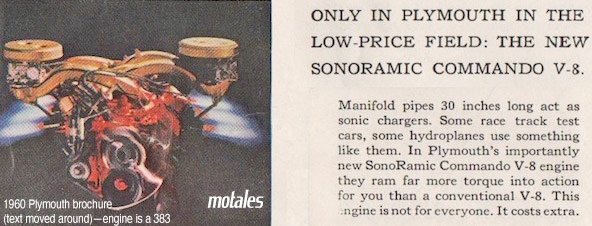

Chrysler engineers had discovered a supercharging effect as air ran raced through intake tubes, bounced off closed valves, and was rammed back in at higher pressure. By changing the length of the valves, they could get a performance boost in some rpm ranges—some engine speeds. (This effect had been discovered when tuning for a 1952 Indy race.) The engineers set the length of the manifold tubes to 30 inches long on special 383 and 413 engines to add power during highway acceleration; to get that length, they had two carburetors, each feeding the cylinders on the opposite side of the engine.

The sweeping curves of the intake were beautiful and unique. People dubbed it the Cross-Ram Wedge, because of the crossing the intake manifold tubes, the ram effect, and the wedge combustion chamber. Regardless, it brought Dodge 330 horsepower and 460 pound-feet of torque. It may have hurt more than helped in racing, where the revs were usually higher

The big change for two-barrel engines in 1960 was a three-stage metering rod for their Stromberg WWC carburetors.

A new feature for the 1961 cars was limited to California: a tube allowed crankcase vapors to be drawn into the carburetor, where they were burned, reducing smog. This closed crankcase ventilation system would later become standard on all cars, cutting emissions without any drawbacks other than another couple of parts. Dodge called their four-barrel performance 383 the D-500 (330 bhp), Polara D-500 (325 bhp), and Dart D-500; they used two-barrel versions as well, without the D-500 name.

For the 1961 cars, the 361’s compression dropped to 9:1 so buyers could use regular-octane gasoline; the 1962 model year was the last one for the 361 four-barrel in cars (it remained in trucks). The 361 stayed on as the low-end two-barrel B engine until the end of 1966, when it was replaced by the 360 cubic inch A-engine. The company did the same trick on the 383 in the 1965 cars—dropping compression on the two-barrel to 9.2:1 so it would run regular fuel.

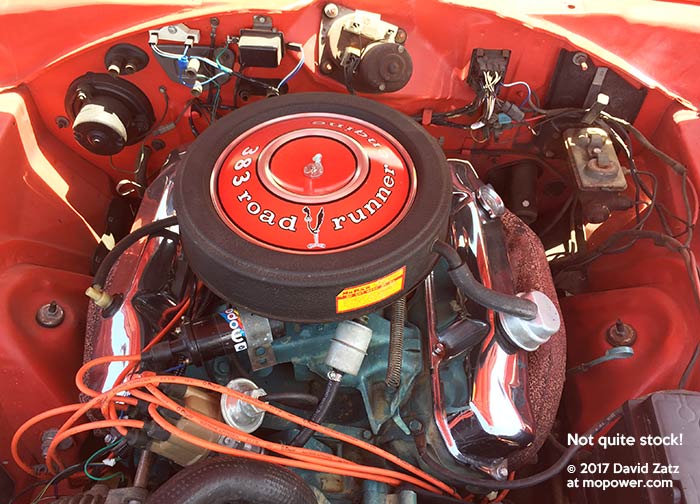

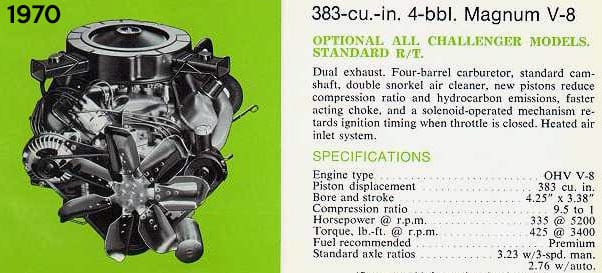

The biggest performance improvement to the B-engines was likely in 1963, when Chrysler restored hemispherical heads to a racing version of the RB 440—but that’s another article. The next big news was the 1968 Plymouth Road Runner; needing an inexpensive engine with higher performance, Plymouth’s Jack Smith asked Engineering to use the 440’s heads, cam, and manifolds on a special Road Runner 383. This special 383 produced 335 horsepower and 425 pound-feet of torque with its single four-barrel carburetor; it was unique to the 1968 Road Runner for one year, as the car’s base engine (three-carb 440s and 426 Hemis were optional). After that, with the 1969 cars, the “hot” 383 was optional elsewhere.

Several forces were gathering to shut down the first muscle-car era. Insurance companies were connecting the dots between crash claims and hot engines, and even Congress was learning century-old facts about lead and carbon monoxide poisoning. The 1965 Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Act authorized regulations on emissions starting with the 1968 cars (trucks were largely ignored).

The 1970 cars were the first to feel the impact, slight though it was at the time. The 383 dropped in compression to 8.7:1 for 1970 cars, and again to 8.5:1 for the 1971s. The two-barrel 383 was still rated at 290 horsepower (4400 rpm) and 390 pound-feet of torque (2800 rpm), well above the four-barrel 340 V8; the four-barrel was rated at 330 hp and 425 pound-feet, on premium; and the 383 Magnum added just five horsepower to the total. (The RB 440 engine turned in 375 horsepower and 480 pound-feet of torque, also running premium fuel.) The 1971 Road Runner’s base 383 four-barrel now output 300 horsepower with 410 lb-ft of torque.

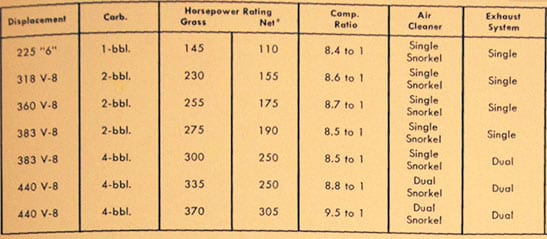

Adopting net horsepower made the drop look far larger and would confuse people for decades to come: it factored in the effects of things like water, oil, and fuel pumps, which are needed for engines to run but which rob engines of some of their power. In the 1971 Road Runner 383, for example, these accessories dropped output from 300 to 250 horsepower—so the net rating was 250, and the gross rating was 300. The engine’s 410 pound-feet of torque dropped to 325. A person could be forgiven for thinking that clean air rules had cost 50 horses and 85 pound-feet of torque—but it was a change in the reporting.

The chart above shows gross and net figures for most of the 1971 Chrysler engines—excluding the triple two-barrel engines.

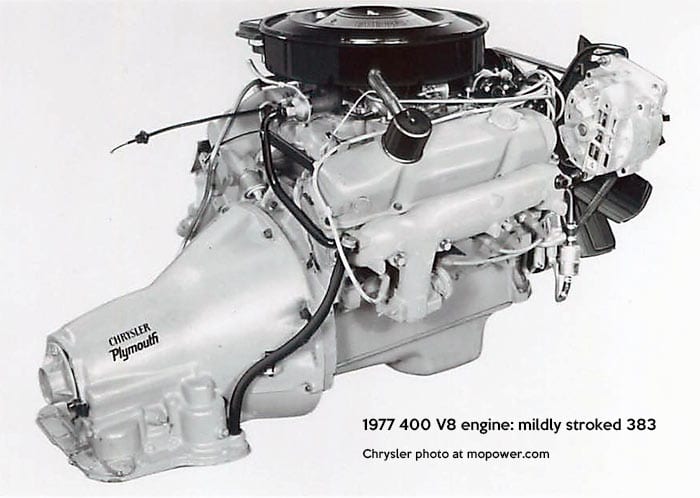

The B engines had different bore sizes, which cost time and money in the Trenton Engine factory which made them. The engineers finally standardized on 4.34” bores for every B engines, which pushed the 383 to 400 cubic inches. (Rick Ehrenberg wrote in Mopar Action that they were going to standardize on a 4.32 inch bore for both the B and RB engines, which would be even more efficient; but marketers didn’t want to stop at 396 cubic inches when they could so easily reach 400.)

The increase in cubic inches countered another drop in compression. The 1972 400 had a net horsepower rating of 190 hp and 310 lb-ft with a two-barrel carburetor, and a healthy 255 hp and 340 lb-ft with the four-barrel. Both versions were thus able to beat their 1971 net ratings, even with the compression drop.

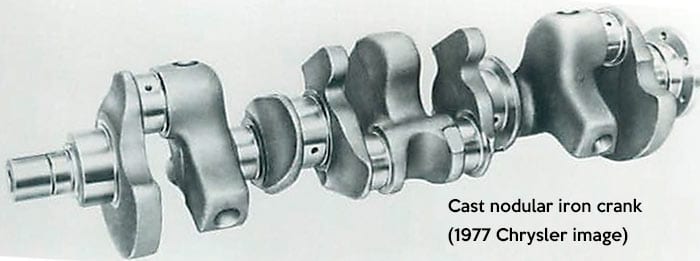

The 400 has generally not gotten the respect of other Mopar engines. It didn’t help that the engineers swithced from the forged steel crank to ductile iron, which required external balancing through a weight in the harmonic balancer. The new cam was durable enough, though.

Electronic ignition came with some of the 1972 cars, and would quickly reach every car and truck; it was a major advance, providing more efficiency at little cost, while eliminating the need to set or replace ignition points.

The 1973 cars had induction-hardened exhaust valve seats, readying the big engines for unleaded fuel. Induction hardening was a simple process of heating the seats to 1700°F, then letting them cool down.

Chrysler engineers worked on avoiding the air pumps adopted by GM and Ford to burn any hydrocarbons the engine didn’t already get to. Tuning engineer Pete Hagenbuch made repeated requests to add fuel injection, which the executives deemed as being too expensive; instead, the Lean Burn system, the world’s first computer-controlled spark advance system, was created and installed on the B engines, and as often as not, removed shortly afterwards.

In 1975, the two-barrel 400 was producing 175 horsepower and 300 pound-feet of torque, which was close the the smaller and lighter 360; they were dropped entirely in 1976. For 1978, the 400 was given twin concentric throttle return springs in addition to the existing torsion-based spring; and every Chrysler engine gained an adapter so their techs could set the timing with the aid of a magnetic probe. By this time, relatively few cars were using the big engines; they were, though, popular in trucks and mobile homes.

Finally, in August 1978, the last B or RB engine—and Chrysler’s very last big block—left the assembly line. The last Dodge truck using one of these massive engines was built in 1979; but a large inventory made them available in mobile homes for years afterwards.

The company had made over three million 383 engines, along with numerous 361s and 400s. It was not bad for a design that took less than two years to create from nothing, without computers.

Books by MoTales writer David Zatz

Copyright © 2021-2024 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.