When Chrysler created its first V8 engines, which debuted in 1951, they chose hemispherical heads for efficiency. The design was the most efficient, but the heads were massive, the assemblies were heavy, and production was slow. That didn’t matter as long as V8s were sold in small numbers, but as demand skyrocketed, the engineers made their engines lighter, cheaper, and faster to build (first using polyspherical heads, then wedge heads). There was one problem they could not fix as easily: competitors were outpacing Chrysler in displacement. Company leaders decided to add a completely new design to their V8 selection; Robert S. Rarey led development, and Fred Shrimton and Ray Latham designed the block..

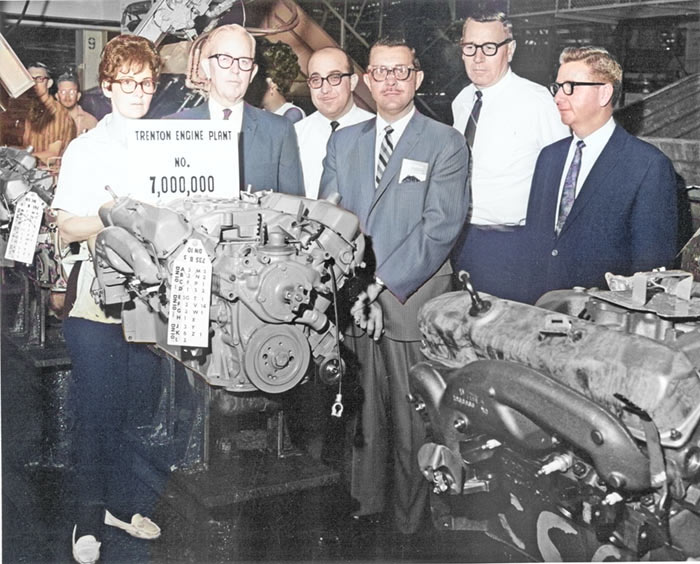

The engines were coded as the “B” series, with the wedge-head versions of the original V8s dubbed “A” engines. The coding was a little more complicated than that: they had two versions of the “B” V8, support 3.38 and 3.75 inch strokes (with top decks 9.98 and 10.725 inches tall). These were designated LB (low B) and RB (raised B). Both were made at the Trenton Engine plant, both had 4.8 inches between cylinder centers, and each series, over the years, spawned exactly four different displacements. Oddly, only two ever shared the same bore.

| LB | 350 | 361 | 383 | 400 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bore | 4.06 | 4.12 | 4.25 | 4.34 |

| RB | 383 | 413 | 426 | 440 |

| Bore | 4.03 | 4.18 | 4.25 | 4.32 |

The project began in 1956; the LB engines were ready in late 1957 for the 1958 cars (most people just called them “B,” as we will from here on). Despite the speed of development, the engines had clever features such as a water jacket whose design avoided steam pockets while saving weight. Other weight-cutting measures were short exhaust ports (so the exhaust manifolds were close to the heads), side-by-side intake ports, and an innovative single embossed sheet-metal gasket to seal the joints between the heads and intake. To handle the power, engineers specified drop-forged steel connecting rods and a forged crank; and attached each head with 17 bolts, up from ten per head on the original V8s. New “tuned” air cleaners were quieter by using the chambers as resonators and by experimenting with snorkel length, using a tape recorder to test various lengths.

The oil pump was on the front bottom left of the block, and the distributor was on the front top right to keep it away from cabin ventilation structures; shaped oil pan sumps were created to make room for the suspension’s tie rods. Stamped steel rocker arms replaced the machined arms of older engines, saving time and money. The cam had a slipper-type grind, with aluminum pistons having steel bands and three rings each. Valves were silicon chromium steel, sodium-filled when used in truck engines. The big V8 was originally paired with a dual exhaust with twin mufflers and resonators, topped by a four-barrel carburetor with an automatic choke. From the start, the RB engines had hydraulic lifters, which did not need adjustment, for the inline overhead valves.

Chrysler’s president, Tex Colbert, was focused on cutting Chrysler’s oversized costs, so all five brands (Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler, and sometimes Imperial) shared the same engines (other than the RB, in its first few years).

The RB engines rolled out a year after the B engines, and were first used in Chrysler’s 1959 cars, but there was a problem. The factory had just two assembly lines, one for the B and one for the RB, and demand for the B engine was far stronger than demand for the RB, which was only used in the company’s most expensive cars. To balance production, the engineers created a 383 cubic inch RB engine, deliberately made the same size as the B-type 383; this balanced out supply until Trenton engineers figured out how to quickly switch a line between B and RB engine production. Thus, there was a unique Chrysler 383 from 1959 to 1960.

| Carb | 2V | 4V |

|---|---|---|

| Car | Windsor | Saratoga |

| bhp | 305 | 325 |

| Torque | 410 | 425 |

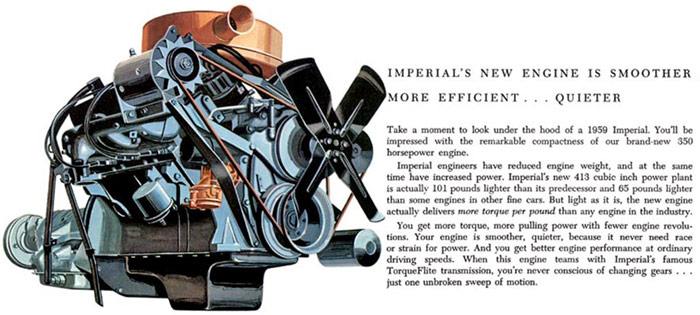

The new 413’s longer stroke was good for strong torque at low engine speeds, making it suitable for luxury cars, while the large displacement bode well for performance cars; in its first year, the 413 powered a car that was a mix of both, the 1959 Chrysler 300E, the first “letter car” to come with anything but a Hemi. With twin four-barrel carburetors, the 300E boasted 380 brake horsepower at 5000 rpm and 450 lb-ft at 3600 rpm (the New Yorker and Imperial were rated at 350 hp and 470 lb-ft). The single-carburetor 413 quickly replaced the expensive Hemi V8 in the Imperial and Chrysler New Yorker; its strong low-end torque was probably better suited to those luxury cars.

| Imperial New Yorker |

300E | |

|---|---|---|

| Compression | 10.1:1 | 10.1:1 |

| bhp | 350 @ 4600 | 380 @ 5,000 |

| Torque | 470 | 450 @ 2,800 |

| Carbs | Four-barrel | Twin four-barrel |

| Valves | Intake: 2.08”; Exhaust: 1.60”; 0.430” lift. 48° overlap |

|

Chrysler’s press release (September 5, 1958) emphasized the increase in displacement first—from the original 350 and 361 cubic inch B-engines to 361 and 383 cubic inches; from the 354 Hemi to the 383 B-engine; and from the 392 Hemi to the 413. Vice president of engineering Paul Ackerman claimed that V8 fuel economy had been increased by up to 10% as well, though that was through gearing, carburetion, manifolds, and aerodynamics. The new B and RB engines, Ackerman said, were also more durable and weighed up to 100 pounds less than the outgoing Hemi V8s, while the oil filter and electrical parts were easier to replace. Valve seats used a better steel alloy, tappet chamber baffles cut oil use, and a stronger oil pump provided greater oil pressure. Finally, a new cooling system cut antifreeze from 25 to 16 quarts from the Hemi designs; this cut warmup time.

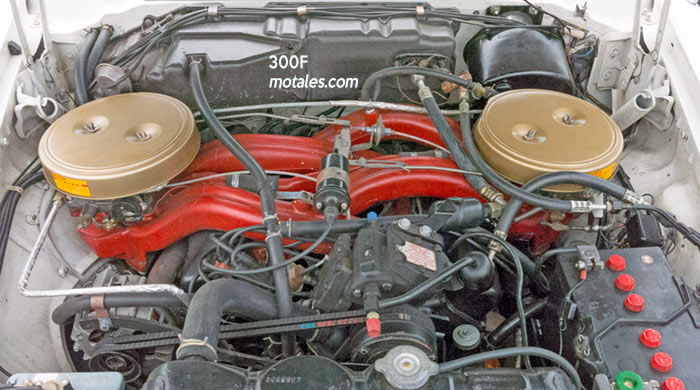

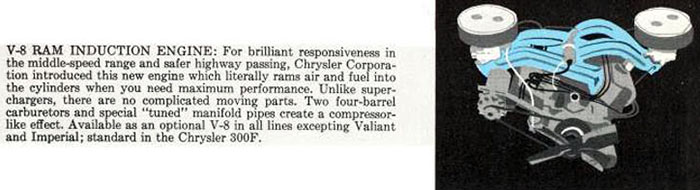

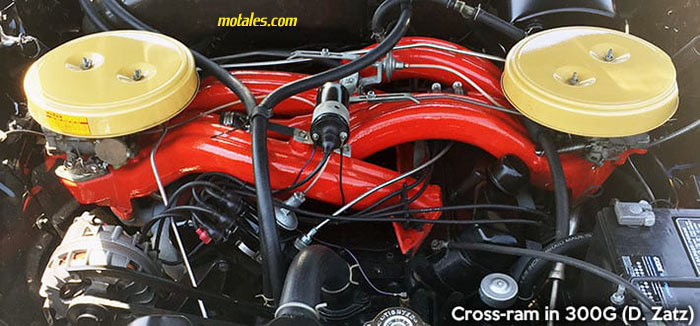

The 1960 cross-ram engines were based on a Chrysler discovery from its racing efforts. The air coming into the carburetor is mixed with fuel, then sent through a tube to the cylinders, on any engine; but when the intake valve was closed, the air/fuel mixture would bounce back into the intake tube for a moment, returning at higher pressure when the valve was open. That created a supercharging effect which could be tuned by changing the length of the intake tubes.

It turned out that 30 inches was a good length for increasing midrange torque (for passing). To get to that 30-inch length, Chrysler created new intakes which put the carburetors on opposite sides of the engine from the cylinders they were feeding. The system was standard only on the 300F, but optional on other cars; torque reached a stunning 495 pound-feet.

The sweeping curves of the intake were beautiful and unique. People dubbed it the Cross-Ram Wedge, because of the crossing the intake manifold tubes, the ram effect, and the wedge combustion chamber. In racing, it was less than a perfect solution, because it did maximize midrange torque but at the expense of high-rev power; the qualities that made it highly effective on the road hurt it in all-out races. What’s more, the peak horsepower rating was slightly lower, for the same reason.

The 1960 300F had two engine options. The cross-ram engine with 30 inch long tubes was standard; an optional engine with shorter, 15-inch tubes had lower torque but more horsepower. The 1961 300G followed the same formula, while the 1962 300H returned to the simpler 1959 setup, dropping the cross ram manifolds entirely.

| Imperial New Yorker |

300F/300G | 300F/300G | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression | 10.1:1 | 10.1:1 | 10.1:1 |

| bhp | 350 | 375 @ 5,000 | 400 @ 5,200 |

| Torque | 470 | 495 @ 2,800 | 465 @ 3,600 |

| Carbs | Four-barrel | Twin four-barrel | |

| Valves | Intake: 2.08”; Exhaust: 1.60”; 0.430” lift. 48° overlap |

||

Other cars continued to run the 413 with single carburetors, a two-barrel or a four-barrel. The big change for the 1960 two-barrel engines was a three-stage metering rod for their Stromberg WWC carburetors. Superduckie pointed out, “There were 413s with two-barrel carburetors, for school buses and dump trucks. There were six blocks, five cylinder-head variations, four camshafts, three timing chains, four flywheels, four torque converters, five different oil pans, and many different linkage brackets.” At that, it was still easier to manage than the Hemi V8s had been, with separate displacements and internal parts for Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler, and Imperial.

| Production by Year | 1959 | 1960 |

|---|---|---|

| Windsor, Saratoga (RB 383) | 47,219 | 52,349 |

| New Yorker, 300E/300F | 17,025 | 20,602 |

| Imperial | 17,262 | 17,719 |

Trucks used special versions of these engines fitted with induction-hardened crankshaft journals, hydraulic valve lifters, rotating sodium-filled exhaust valves, chrome-alloy cast-iron blocks, and special rod bearings for durability.

| Firing Order | 1, 8, 4, 3, 6, 5, 7, 2 | |

| Valves | Overhead, in-line, hydraulic valves. | |

| Piston and Rings | Aluminum alloy pistol with three rings | |

| Crankshaft | Drop forged steel | |

The 1961 cars sold in California had a tube which drew crankcase vapors into the carburetor, where they were burned; this positive crankcase ventilation system later became standard on all cars, because it cut emissions without any drawbacks. The RB-383 engine was no longer needed, so the only RB engine was the 413.

Police could outfit their Plymouths or Dodges with the 413, producing 375 hp and 450 lb-ft with four-barrels, or 350 hp and 470 lb-ft with two-barrels. This was a fairly unusual case of the police getting more power than civilians (who had to pony up for a Chrysler to get that much power).

Limited edition 1962 Dodge Ramcharger and Plymouth Super Stock cars had a 413 Max Wedge option; sold for drag racing, these boasted an official 410 bhp. These cars were street legal, and optional in sedans, hardtops, and convertibles, but were not tuned for street use. With a high compression ratio, new aluminum short-tube (15-inch) ram intake, dual four-barrels, and a high velocity exhaust, they set four class records in 1962 NHRA racing, with common mid-twelve-second quarter-mile runs. Port areas were 25% larger than standard. Dealers were told not to sell them to anyone but “a dedicated competitor” because of the rough and high idle; it would “not produce a smooth or satisfactory performance under normal city or traffic driving conditions...” At least one engineer who drove a Super Stock car agreed; it ran very poorly when cold and was not set up for bad weather.

Normal 1962 production cars saw a slight change in compression (to 10.0:1) and a 10 bhp drop, without any change in torque. Chrysler now advertised both the 383 and 413 as the “Firepower” engines with their horsepower (the original V8, with hemispherical heads, was introduced as the FirePower V8, so this could be confusing). The “Firepower 340” was 340 bhp, for example. The Firepower 380 (dual four-barrel carburetors), was standard on 300H and New Yorker, optional on other Chryslers. The lowly Newport had to make due with the “Firebolt” (a B-type 361 rated at 265 bhp) or “Firepower 305” (a B-type 383). A 405-bhp version 413 was optional for the 300H. At Dodge, the Ramcharger 413 (11:1 compression) produced 410 bhp; a 13.5:1 compression version produced 420 bhp. Each had dual Carter carburetors—the 410 bhp version using AFB 3859S, the 420 bhp version using the AFB 3084S. Plymouth had the same options but under different names.

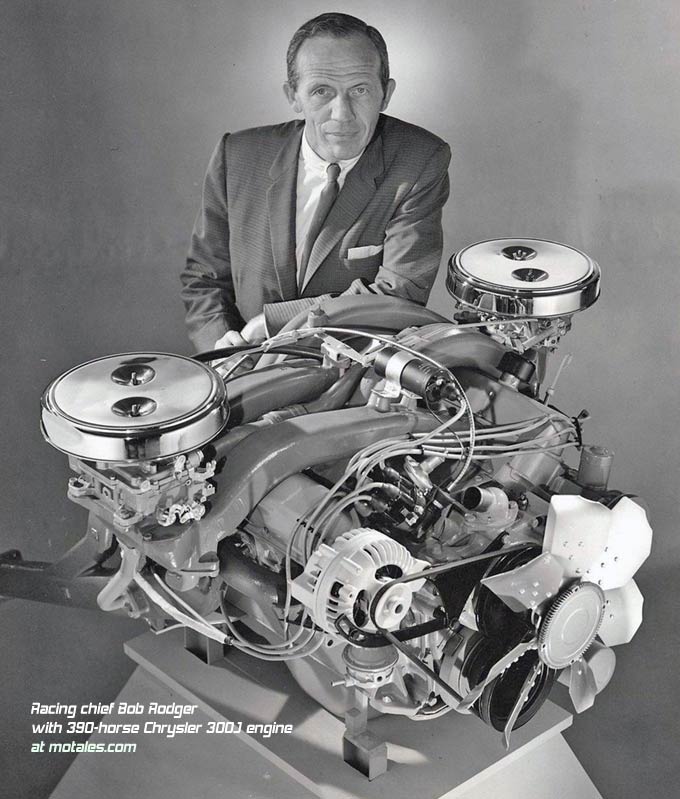

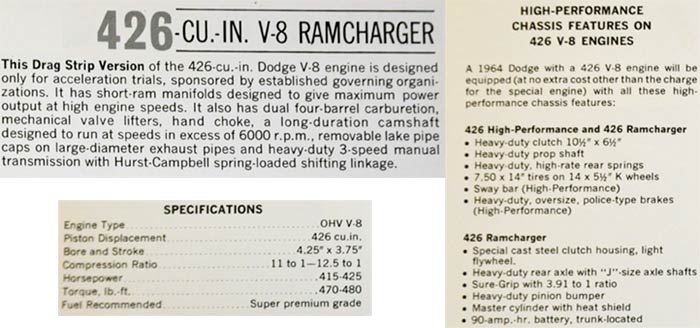

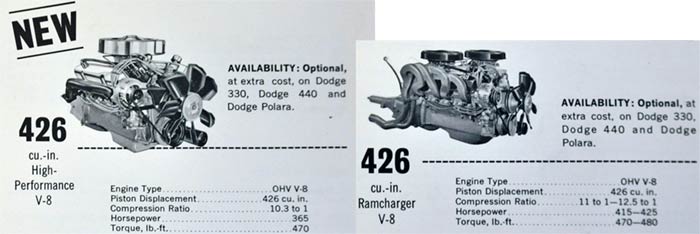

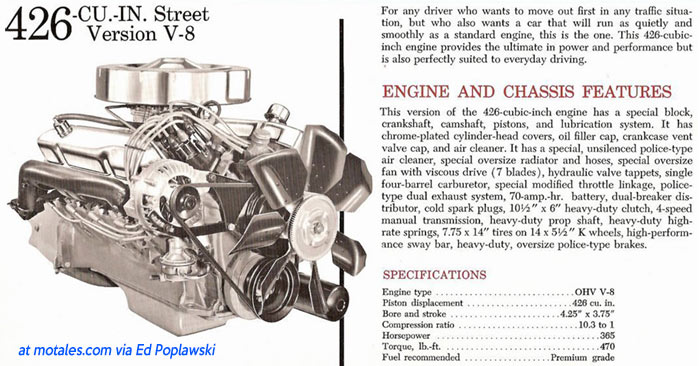

Chrysler released four new engine versions for the 1963 cars; these 426 cubic inch engines were created by increasing the bore. They were coupled with high-performing 300J heads or normal-performance 516 heads, topped by a single four-barrel carburetor; the 11.1:1 compression engine was rated at 370 bhp, while the 13.5:1 compression option brought 375 bhp. The Chrysler 300J had a choice of a 390-bhp 413 or a 415-425-bhp 426—but only 400 300Js were made, and it’s hard to say if any really had a 426 Max Wedge in their 300J. Regardless, the base 300J engine returned to the cross-ram wedge design, even though the 300H had used conventional manifolds.

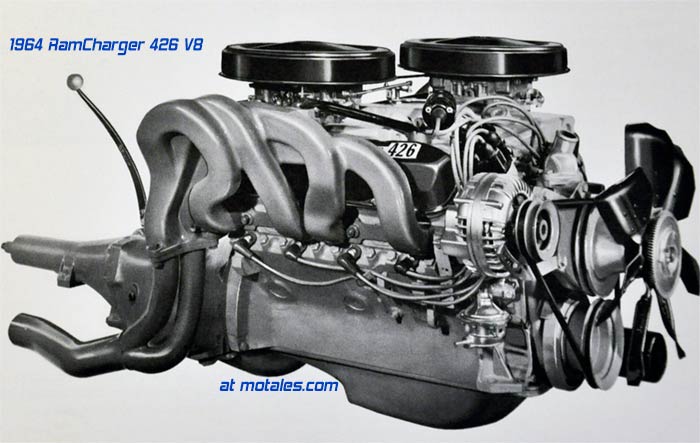

The 413 Max Wedge was replaced by a 426 Max Wedge (not to be confused with the 426 Hemi), still meant for racing only. It was rated by Dodge at 415-425 gross horsepower and 470-480 lb-ft of torque; the 413, at 410-420 hp and 460-470 lb-ft. The new 426 Max Wedge engines dominated NHRA’s Super Stock class and the Stage II motors boosted NASCAR racing wins. Ronnie Sox won Top Stock Eliminator.

Some of the changes involved in making a Max Wedge were:

Dodge’s 1963 brochure mentioned the special optional 426: “This is our maximum performance engine, so maximum it can be recommended for all-out performance specialists only.”

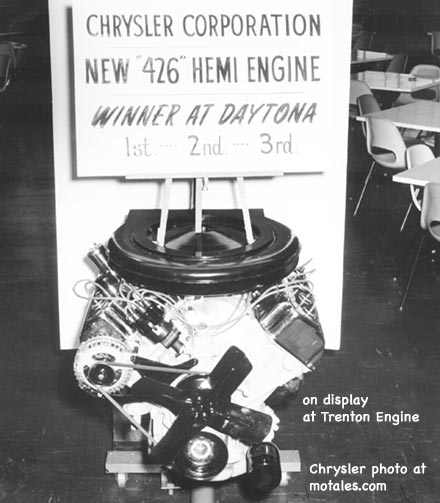

For racing only, Chrysler topped the 426 Wedge with hemispherical heads—but that’s another article. The A-864 Hemi was a professional-racing-only engine in the 1964 Plymouth and Dodge cars.

Dodge Ramcharger drivers continued to pile up records with the 426 Wedge, now using Carter AFB-3705S carburetors; the Ramcharger package included special air horns, primary riser openers in the intake manifold, cams, combustion chambers, intake valve ports, head gaskets, fans, and optional aluminum front-end packages that cut nearly 150 pounds. In the 1964 brochure (above), Dodge called it both the “special competition engine” and the Ramcharger V8; and the sale was again limited to “recognized and qualified” racers only.

The 1964 cars had an optional dual-carb, 10.3:1-compression 426 with hydraulic tappets and an aggressive cam (268-268-48) dubbed either Commando 426 (Plymouth) or Ramcharger (Dodge). It came from the factory with chrome-plated valve covers and air cleaners; Dodge noted it could be retrofitted into other cars by modifying the lower hood panel. On the other side, Chrysler had the 361 and 383 B-engines with two-barrel carbs on its lower cars; the base four-barrel 413 in New Yorker and Imperial ran 340 bhp, the base four-barrel 413 in the 300K (with a dual exhaust) was 360 bhp, and an optional dual-carb 300K engine was 390 bhp.

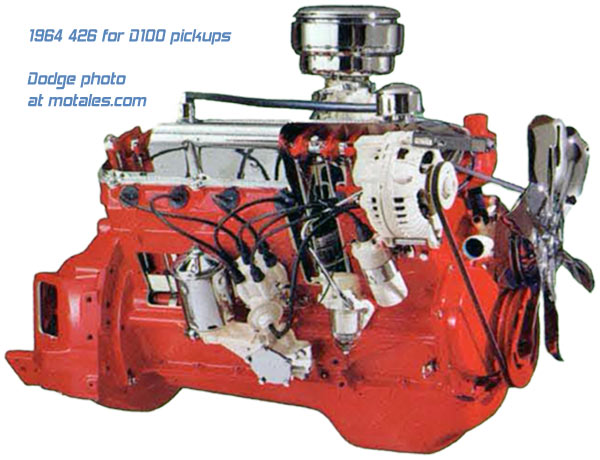

The Dodge D100 Custom Sports Special pickup truck, a full-size light-duty pickup, started with the extremely tame (140 bhp) slant six; but buyers could opt for a 200 bhp small-block V8 or the 426 Wedge (365 bhp version). It used the “hot” cam with a single four-barrel carburetor and had the same power ratings and chrome treatment as the Commando 426/Ramcharger V8.

It’s hard to imagine the rationale for keeping the 413 around while making the 426, given how close they were in design and displacement; perhaps they felt the 426 cubic inch size was a “performance brand” of its own, especially given the publicity around the racing-only 426 Hemi.

In 1965, Dodge made the 340-bhp 413 and the 365-bhp 426 optional in selected cars, allowing buyers to pair the 413 with two axle ratios (2.76 and 3.23) and with or without SureGrip differentials, but only with automatic transmissions. The 426 could be paired with a four-speed manual or three-speed automatic, with or without SureGrip, and only with a 3.23 ratio. The situation at Plymouth was similar.

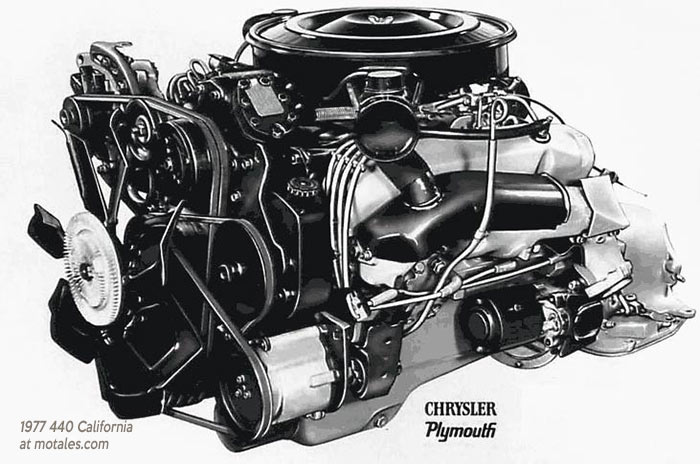

With new casting techniques, Chrysler increased the bore to 4.32 inches, resulting in the 440, Chrysler’s largest ever V8 and the final permutation of the RB engines (not counting the Street Hemi, which was a retuned version of the race Hemi). The 440 replaced both the 426 Wedge and the 413 in cars; the 413 would continue to be used in medium and heavy duty trucks until 1979.

The basic 440 had 350 bhp, 480 lb-ft, and 10.1:1 compression and was standard on the New Yorker and Imperial. A more powerful version, with a hotter cam and other performance measures, produced 365 hp with the same compression; torque was unchanged. Chrysler dubbed the higher performance version the “TNT” and made it optional on the 1966 New Yorker, Newport, 300, and Town & Country wagon; Dodge made it optional on the Dodge Polara and Monaco (the Coronet 440, a trim level created before the engine was made, was not available with a 440). Plymouth dubbed the high-power 440 the Commando—the same name they used for the 383 in both two and four barrel form—and made it an option on their big cars. The rollout had some points of interest:

The cam, shared with 383 cubic inch “B” engines, had more aggressive timing and higher lift:

| Valve Lift | Standard | High Perf. |

|---|---|---|

| Intake | 0.425” | 0.450” |

| Exhaust | 0.437” | 0.465” |

| Hemi | 0.480” |

(426 “Street Hemi” valve lift would be 0.490” intake, 0.480” exhaust.)

Valve diameter was the same for both engines—2.08” intake, 1.74” exhaust, compared with 2.25” and 1.94” on the later 426 Hemi. The valve opening on the “hot” cam was also aggressive, though not quite as aggressive as the Hemi:

| Valve Opening | Intake | Exhaust |

|---|---|---|

| 383/440 (standard) | 256° | 260° |

| 383/440 (high perf.) | 268° | 284° |

| Street Hemi (1970) | 284° | 284° |

In addition, as one might expect, high-performance versions for racing replaced the 426 Wedge; now, 426 cubic inches were reserved for the (RB-based) Hemi.

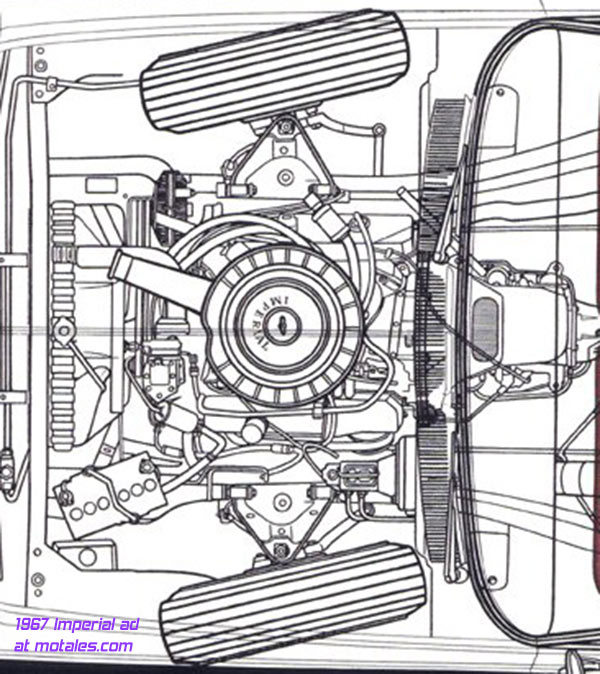

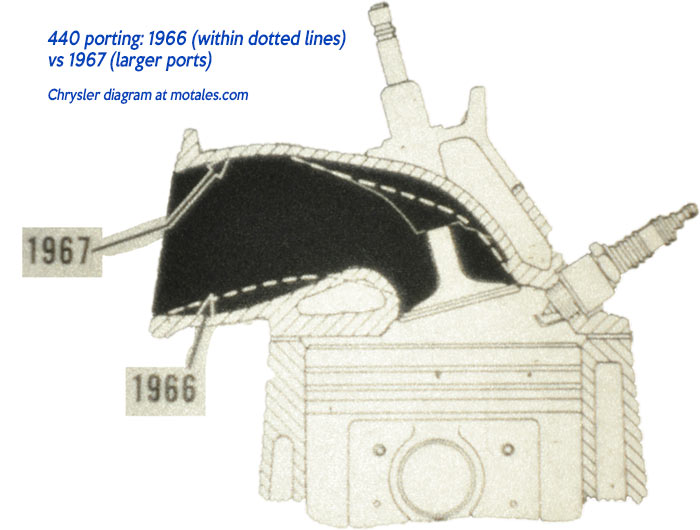

For the 1967 cars and trucks, Chrysler engineers optimized the 440’s port shapes and sizes. This did not change the rated power, but as the diagram below shows, should have increased air volume at high engine speeds. The company also enlarged the manifold passages for better breathing.

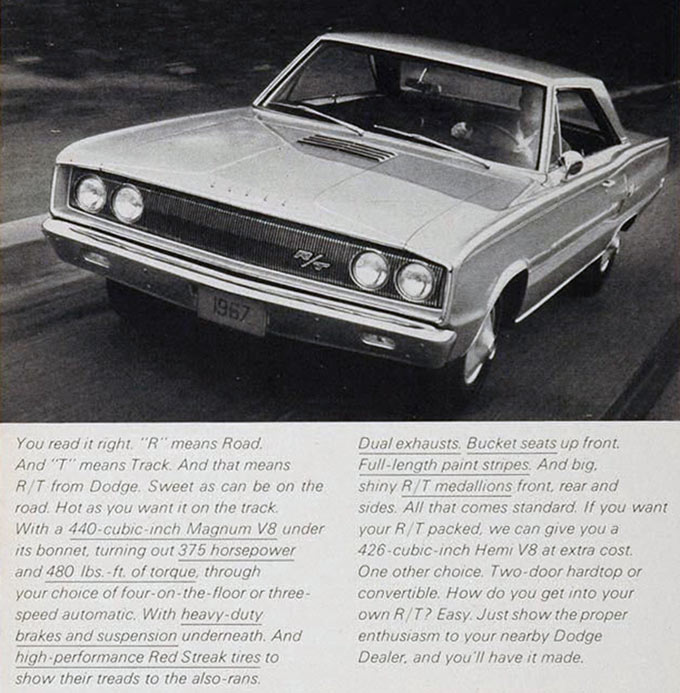

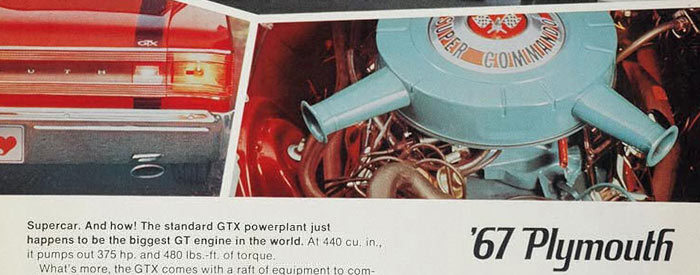

Dubbed Super Commando 440 by Plymouth; Magnum by Dodge; and TNT by Chrysler, 1967’s high-performance, hot-cam 440 had twin-snorkel air cleaners, dual exhausts, and larger exhaust valves; while the standard engine used a Holley four-barrel, the high-performance version had a Carter AFB four-barrel. The new cam increased both valve opening duration and valve lift.

Optional on some 1967 cars, and standard on the GTX, Coronet R/T, and Charger R/T, the new high performance 440’s output was 375 bhp, with the same 480 lb-ft of torque. Road & Track measured a 1967 Coronet R/T’s 0-60 mph as 8.6 seconds; 0-100 as 28.5 seconds; and the quarter mile as 16.6 seconds at 83 mph. The car weighed 4,230 lb as tested.

The 1968 model year saw some Clean Air Act responses, including a CAP valve to advance spark timing under certain conditions (which did not make it to the 1969 cars, at least in the B and RB—it remained on the 170 slant six and 426 Hemi, Mopar’s polar opposites). Initial spark retarding was changed, only, again, to be changed back for the 1969 models.

Select 1969 cars had a new and potent option: the 440 Six Barrel / Six Pack (names used by Plymouth and Dodge, respectively). After three months of production, Chrysler started using heavier connecting rods, which required new crankshafts, vibration dampers, and flywheels; the parts should not be mixed between generations. (The heavy connecting rods were used on all 440 high-performance engines starting with the 1970 model year, and continuing until 1975.) From midyear 1969 to early 1970, the triple-carburetor setup used a high-rise Edelbrock manifold.

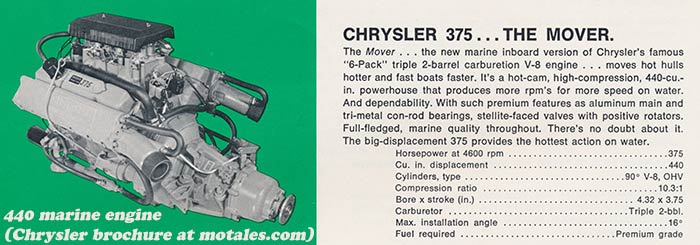

It didn’t take long for the company to issue truck and marine versions of their engines, with changes to adapt them to their new roles. One unexpected result was the Chrysler 375 marine engine—a 440 “6-Pack,” and a bar-bet winner since “6-Pack” was nominally a Dodge name (Chrysler also used it on Australian Valiant Chargers with straight-six engines). The truck 440 did not have a triple-carburetor option.

The triple-carb 440 car engine was rated at 390 bhp and 490 pound-feet of torque, and included a long-duration 268-284-46° camshaft (shared with the four-barrel high performance 383 and 440) and a 10.5:1 compression ratio. Ronnie Sox tested an unprepared Road Runner with this setup and a four-speed manual transmission at the Cecil County Dragway; he ran quarter miles at an average of 13.1 seconds at 111 mph (an amateur driver clocked in at 13.5 seconds at 109 mph). The 440 with three carbs could give a 426 Hemi a run for its money.

The specimen below, from a 1970 car, had a “Shaker” hood—actually an air-cleaner-sized hole in the hood (the rubber around the air cleaner connected with the hood), through which the actual air cleaner popped out, vibrating as the engine did.

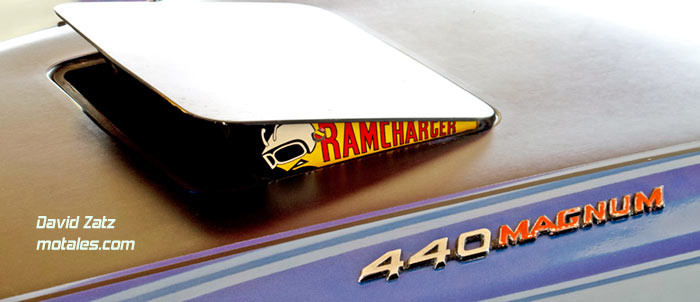

Customers could also opt for an Air Grabber hood with their 1969 Dodge or Plymouth (depending on the model). This was a cold air intake in the hood which the driver could open or close at will; in theory the reason for closing the door was to prevent water from getting in on rainy or snowy days, though it was also handy when pulling up next to a police car or trying to have a low profile before street racing.

Clean Air Act accommodations for 1969 were increasing idle speed by 50 rpm to improve fuel distribution; refining choke modulation (rebalancing thermostatic and vacuum control); and flow-testing carburetors at eight different points to keep variation low. The Imperial gained a solid state voltage regulator.

For 1969, the 440 was standard on the Imperials and the Chrysler New Yorker, 300, and Town & Country; the hot-cam version was standard on the GTX, Charger R/T, Charger Daytona, Coronet R/T, and optional on all Chryslers other than the wagons. On some vehicles it was sold with an optional Super Track Pac, including a four-speed manual transmission, 3.55 axle ratio, viscous fan drive, dual-breaker distributor, and Sure-Grip differential; or, optionally, disc front brakes and a 4.10:1 axle. The standard transmission with either 440 was the A-727 TorqueFlite three-speed automatic. Power ratings were still 375 bhp/480 lb-ft.

These engines were efficient for their time; from 1960 to 1968, the B and RB engines powered class winners in the annual Mobil Economy Runs. The RB 413 and 440 (and the LB 361) did well powering the Chrysler New Yorker, 300, and Newport, as well as the Imperial.

Clouds were gathering, though. Insurance companies were belatedly realizing that high-power cars with primitive brakes and handling resulted in more crashes. Stricter rules to handle lead (a poison put into gasoline to increase octane) and carbon monoxide were being developed. Finally, car company executives were likely less than overjoyed about spending heavily on largely low-volume cars, such as anything with a Hemi. These would all combine in 1972 to reduce the 440’s potency and, coupled with gasoline crises from 1973 on, to eliminate it entirely before the end of the decade.

For 1970, the 440’s compression fall from 10:1 down to 9.7:1, but output ratings did not change: 375 horsepower and 480 pound-feet of torque. For 1971, the drop was more severe—from 9.7:1 down to 8.8:1—dropping the normal 440 by 15 bhp, to 335, and the hot-cam version by just 5 hp, to 370.

| BHP | Normal 440 | Hi-po 440 |

|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 350 | 375 |

| 1970 | 350 | 375 |

| 1971 | 335 | 370 |

Confusingly, the 1971 model year was also a transition from gross (brake) horsepower to net horsepower; both were listed for 1971 and only for 1971. Brake horsepower was measured with no air cleaner, alternator, water or fuel pump, muffler, and tailpipe; net horsepower tested an engine as it would run inside a car. While this provided a better picture of real performance, it came just as engines were getting lower compression, and even today some think that emissions equipment was causing, say, the 440 to fall from 375 horsepower in 1970 to 250 horsepower in 1971—a fallacy, to say the least.

| 1971 | Gross (bhp) | Net (hp) |

|---|---|---|

| 440 Std | 335 | 250 |

| 440 HO | 370 | 305 |

| 440 6V | 390 | 330 |

Chrysler’s 1971 filing with the auto manufacturers’ association recorded these specifications, as well:

| 1971 | Normal | Hi-po | Triple Carb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horsepower | 335 @ 4400 | 370 @ 4600 | 385 @ 4700 |

| Torque | 460 @ 3200 | 480 @ 3200 | 490 @ 3200 |

| Cam | 260-268-38 | 268-284-46 | 268-284-46 |

| Compression | 9.0 | 9.7 | 10.5 |

| Exhaust | Single | Dual | Dual |

| Fuel | Regular | Premium | Premium |

In 1971, Chrysler cut costs by switching the B and RB engines to a cast iron crankshaft on automatic-transmission cars. This was the swan song for the Hemi, which did not make it to 1972. On July 4, 1971, four cars with 426 cubic inch engines and ported 440 heads were entered in the Daytona Grand National race, finishing 1-2-3-4.

Electronic ignition arrived on some 1972 cars (with the 340, 400 four-barrel, 440 four-barrel, and 440 triple-carb), adding efficiency and cutting maintenance. Electronic ignition, based on company literature, appears to have been standard on all RB car engines for the 1972 model year, with varying availability on lesser V8s. This advance was unfortunately accompanied by a drop in compression on the RB engine to 8.2:1, so that net ratings were now 225 hp (single exhaust/single snorkel), 230 hp (single exhaust/dual snorkel), or 245 hp (dual exhaust/hot cam). Torque ranged from 345 to 360 lb-ft depending on the air cleaner (single/dual snorkel) and exhaust. On the high performance version, ratings were 280 hp/375 lb-ft normal, 290 hp/380 lb-ft with the Cold Air Pak.

The triple-carb 440 enjoyed its final year with the 1972 cars, with a drop to 10.3:1 compression ratio still yielding a respectable 330 hp and 410 lb-ft of torque—net. That makes it roughly the equivalent of today’s highly optimized and fuel-injected 5.7 Hemi (Charger figures shown below), except that it generated a great deal of torque at low engine speeds; it would likely outrun a 5.7 Hemi, but not by a large margin.

| 440 6V | 5.7 Hemi | |

|---|---|---|

| Horsepower | 330 |

370 |

| Torque | 410 | 395 |

The Hemi was not the only casualty from 1971 to 1972; the Coronet R/T, Charger R/T, Charger Daytona, and Coronet R/T were all gone, too. The 1972 Charger Rallye and SE could still be ordered with the 440 four-barrel, and Rallye could be ordered with the still-quite-powerful Six Pack; but the biggest standard Plymouth or Dodge engine was now the “LA” series 360 V8. Imperial and all Chryslers but Newport kept their standard 440s. The 440 was available in trucks and SUVs (such as the Trail Duster) but we are only listing car use for now.

Another engine changed from 1971 to 1972: the last 383 was used in the 1971 cars. To save money, leaders decided to standardize the B and RB engine bore sizes—and then decided that it would be nicer to expand the old 383 to 400 cubic inches, instead of stopping at 396 (which is what it would be if it used the 440’s bore). That meant they did not actually save any money, but they did have a nice even 400 cubic inch B-engine.

New for 1973 were across-the-board electronic ignition, exhaust gas recirculation, and electric-assist chokes; the latter cut the choke out more quickly (sometimes too quickly) to save fuel and reduce emissions. The standard 440 was down to 215 or 230 horsepower (with single and dual exhaust, respectively) and 345 pound-feet of torque—still respectable—with an 8.2:1 compression ratio, so drivers could use regular octane fuel. 1973 police cars still got the high-performance version, rated at 280 hp and 380 lb-ft of torque, with the same 8.2:1 compression and regular fuel requirement.

| net HP |

Normal 440 | Hi-po 440 |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 250 | 305 |

| 1972 | 225-245 | 280-290 |

| 1973 | 215-230 | 280 |

| 1974 | 230 | 275 |

| 1975 | 215 | 260 |

| 1976 | 205 | 255 |

| 1977-78 | 195 | 245* |

* 1978 high performance 440 shows up in some literature but might not have been produced.

Starting with the 1973 model year, Chrysler engines had hardened exhaust valve seats to they would be ready for unleaded fuel; and new radiator overflow reservoirs kept antifreeze in use, rather than dumping it on the ground when the engine heated up. However, the company started using nodular cast iron cranks instead of forged steel parts, to save money.

In the 1974 cars, 440 availability was the same: standard on Imperial and Chrysler (except Newport), optional on Newport, big Dodge and Plymouth cars, Charger, Road Runner, and most police cars. By now, all RB engines had electronic voltage regulators. As in the past, California cars took a hit—in this case, they were rated at 220 hp vs the federal engines’ 230 hp on the ordinary engine. The “hot cam” version continued, with 275 horsepower.

The hot-cam 440 was dropped from civilian brochures for 1975 cars, but police could still get it, with a 260 hp rating (with 355 lb-ft of torque). Standard 440 availability carried forward, with 215 hp (lower in California). EPA gas mileage figures were, for four-barrel cars (Charger and Chrysler New Yorker figures were the same):

| Engine | city/highway mpg |

|---|---|

| 360 | 11/18 |

| 400 | 11/15 |

| 440 | 10/16 |

The standard version of the 1976 440 V8 was rated at 205 hp (200 in California) and 320 lb-ft of torque. The higher performance variant appears in the 1976 police pursuit car brochure, rated at 255 horsepower and 355 lb-ft of torque, and the Standard Catalog cites a figure of 250 hp in California. We do not know if any were actually sold.

Chrysler engineers, trying to avoid the use of air pumps, created the world’s first computer-controlled spark advance system—calling it Lean Burn. Launched on B and RB engines, it would advance in scope, efficiency, and durability nearly every year until the last Chrysler engine with a carburetor left the assembly lines.

Lean Burn was standard in all B and RB engines in 1977 cars; a year later, in the 1978 cars, twin concentric throttle return springs joined the existing torsion-based spring, and a magnetic probe adapter was added to make it easier to set the timing. 440 engines were installed in two pre-production Dodge Li’l Red Express Trucks created for Canadian car shows—at least one of these was sold to a person. (The production Li’l Red Express was 360-powered.) For both 1978 and 1979, ratings were:

Finally, in August 1978, the last B and RB engines, Chrysler’s only big blocks, left the assembly line; the 400 and 440 were the last of their lines. The engines had been kept in production for big cars and for trucks; and the last of the biggest Chrysler Corporation cars, the C-bodies, were made in late 1978. Truck and RV production did not justify continued B/RB production. Rear wheel drive cars, from this point until their end in 1989, would have just two V8 engines—the 318 V8 and the 360 V8 (the latter becoming truck-only well before 1989). Both of these, destined to be the final Chrysler Corporation V8 engines, were distant descendants of the very first Chrysler V8s, the old “double rocker” Hemis.

The last Dodge truck using a Mopar big block was built in 1979; more engines were taken out of inventory and put into RVs until the supply ran out.

Chrysler Corporation had made enormous numbers of B and RB engines. They had powered luxury cars, garnered racing victories and street credibility, and helped with the creation of a major RV business. Overall, they did quite well for a design that took less than two years to create—a testimony to the ingenuity of Chrysler Engineering.

Books by MoTales writer David Zatz

Copyright © 2021-2024 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.