The Daytona is famously a Dodge—either the Dodge Charger Daytona that set a long-standing speed record, or the Dodge Daytona front-drive sports car with its optional turbo engines. But there may have been a Plymouth Belvedere Daytona to homologate an FIA 1965 Plymouth Belvedere in the Daytona Continental Road Race, which Chrysler was interested in due to NASCAR’s (phony) ban on factory supported racing.

Product planners intended for their Daytona Continental racing car to be homologated (have a street-legal version for the general public); it’s unlikely the street version would have been called the Plymouth Daytona Continental, but may have been launched as, say, the Plymouth Belvedere Daytona. (Lincoln may have had something to say about using the Continental name.)

The Daytona Continental Road Race was a 1240-mile (2,000 km) race for GT cars and factory prototypes. Product planners considered making an early Plymouth B-body car as a GT car, running a super stock version in the race. The prototype was Car 023, weighing in, in final form, at 3,850 pounds with all liquids but no driver. It was quite large compared to the typical cars running in the field, generally European or European-style cars such as Ferraris, Corvettes, and AC Cobras. The first race, in 1962, was won in a Lotus; Ferraris took the next two races. And then Plymouth stepped in.

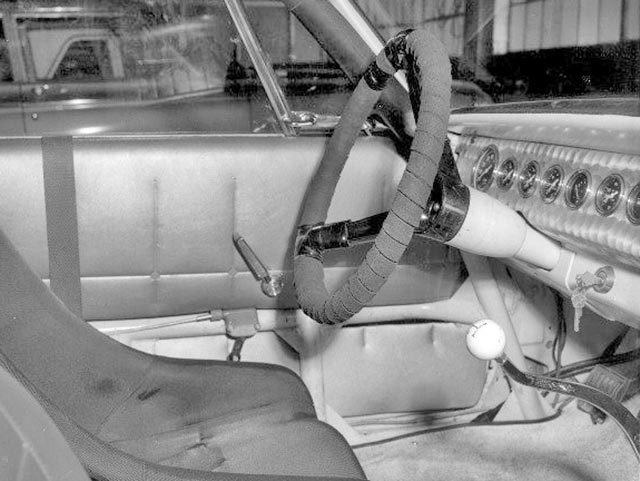

Modifications to the Plymouth included a revised hood, so the super stock engine, with twin four-barrel carburetors, would fit; moving the battery to the trunk and mounting a spare tire in the rear; and adding fuel capacity. The lights were protected by bulbous covers which may have been meant as an aerodynamic touch, but maybe not. Kept in place were the stock door handles, vent windows, and such.

The car, thus modified (and fitted with a 426 Hemi V8 racing engine), was brought to the track at Sebring for three full days of testing and brake evaluation. Fuel economy during these trials was around 3.5 mpg at first; they were able to increase it to 4 mpg by leaning the part-throttle mixture and reducing the accelerator pump stroke.

The engineers on the project found that the brakes used in NASCAR and USAC road races were not ready for GT racing, despite extra brake cooling; there was just not enough time to cool down the brakes. The engineers recommended adding more positive air ducting.

The A-833 four-speed manual transmission itself performed well, aided by a Harrison cooler and Stewart-Warner pumps; but the shift linkage had some issues, fixed by intentionally misadjusting it and adding a heavier reverse crossover spring. Then it was discovered that the synchronizer bands had rotated after a hundred miles; pinning the bands fixed that.

The throttle linkage opened too quickly, but before the race, they added linear linkage so the driver could match engine revs. Other changes based on the test included higher windshield-wiper tension, a driver ventilation setup, and a windshield defroster; they also added a remote brake booster and new roller bearing axle assembly. Then it was time to prepare the car for the race: magna-fluxing key parts, adding the air ducts for the brakes, and reinforcing both fuel tanks.

Renamed to car #30, the Plymouth went to Daytona for three days of practice before the race. That gave the racers (Scott Harvey and Pete Hutchinson) and engineers time to work on the tire compound, brake linings, oil and fuel economy, spark plug tuning, and suspension setup; lap times were managed so they could run the full race without changing brake pads. Overall, they ran 102 laps during practice, with 3.8 miles per lap. That created a leak in the axle assembly, so a new one was fitted.

Because of the lack of time, they ran with the practice engine after replacing the exhaust rocker arms. It qualified #11, with a lap time of 2:23.

An unscheduled lap 18 pit stop revealed that a Champion N57R plug had gone bad because the side wire had lost its press fit to the body. They also realized they didn't need to change tires until 80 laps (though due to a misunderstanding the driver pulled in for tire replacement at 40 laps).

At 50 laps, the driver saw a low oil pressure indicator in turns; then, at 52 laps, the engine failed, due to a connecting rod bearing failure.

What happened to Chrysler’s efforts in the Daytona Continental race? Sanity re-appeared in Highland Park; they decided to step out and leave the race to the small, low-slung sports cars.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky