In 1927, Chrysler started selling its first marine engine; and for decades, it would make special versions of its car engines for the marine and industrial uses. But Chrysler did not really get into the boat business until its 1965 purchases of sailboat maker Lonestar and West Bend Outboard.

West Bend made 29% of marine engines sold in the United States from its 590,000 square foot factory in Hartford, Wisconsin (northwest of Milwaukee). The company’s outboards were also sold under the Elgin and Sears labels. Regardless, West Bend’s attractive styling housed motors with a poor reputation for quality, and which were noisier than competitors’ outboards. Chrysler marine engines were the opposite, known for running well. In any case, in 1965, West Bend became the Chrysler Outboard Corporation, and the outboards were re-engineered to solve their noise and reliability problems.

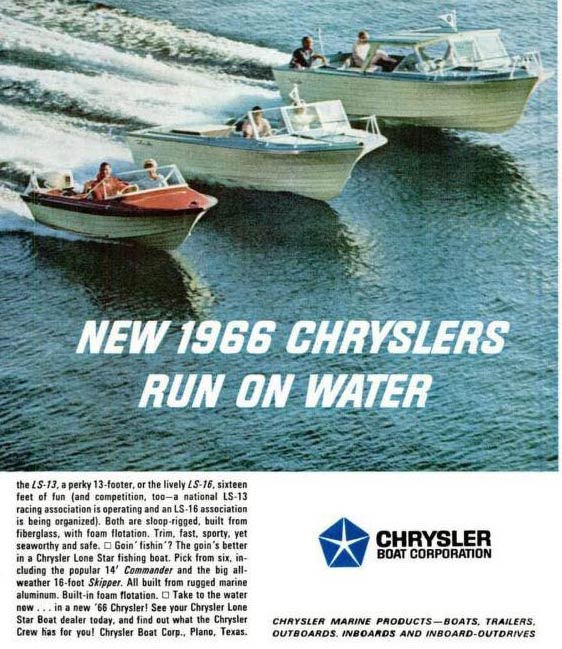

Lonestar Boat was in Plano, Texas, and became the Chrysler Boat Corporation. The company’s sales shot up when they were purchased by Chrysler, partly due to name recognition; their products were, for a time, sold under the “Chrysler Lone Star” label. The acquisition was likely unrelated to Lonestar’s new boat for 1964—named, as Chrysler’s new 1964 Plymouth, Barracuda (the boat was a 13-footer). Together, the companies were integrated into the new Marine and Industrial Products Operations division, which was in turn part of Chrysler’s Diversified Products Group.

Why did Chrysler decide to splash out into boats? A new company president, Lynn Townsend, was trying to increase the company’s global footprint and expand outside of the fashion-driven, roller-coaster-like automotive business; he pushed for expansion into Europe, with the purchase of part of Rootes and SIMCA (later, all of both), and the boating industry was, if no less recession-prone, at least not quite as fashion-crazed as the auto trade.

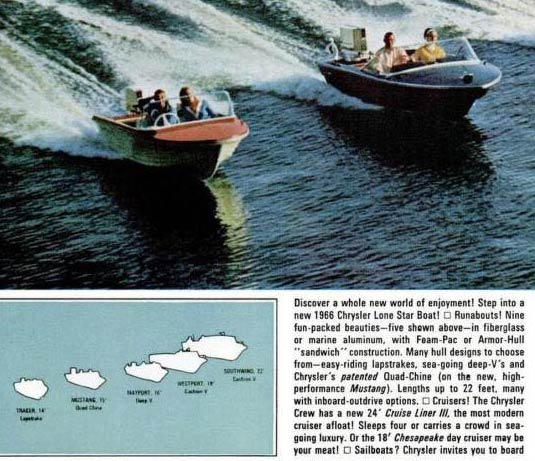

Lonestar was the real key to Chrysler’s new boat business. The company made fiberglass and aluminum boats; the aluminum ones were formed on a thousand-ton press, with smooth seams created by using strippet-punching and heli-arc welders. The exterior was coated, and polyurethane foam was poured into the gap between the floor and hull. Likewise, most of Lonestar’s fiberglass boats used a process they called “Foam-Pac,” which included rigid polyurethane foam between the floor and hull, which in both cases made the boats nearly unsinkable as well as quieter and stronger. The fiberglass boats used both rivets and sealants for strength and durability; the surfaces were coated with UV blockers and gelcoat.

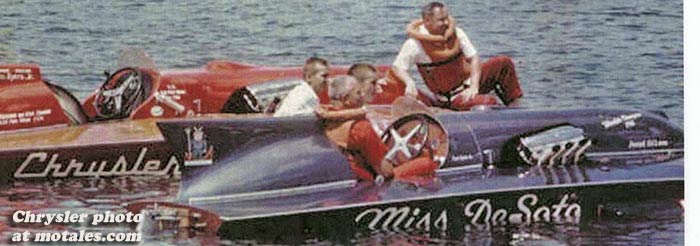

Trailers followed in 1966; they were engineered for each boat. Chrysler also went racing with boats including the Miss Chrysler Crew, a dual, supercharged 426 Hemi-powered hydroplane; the engines were made by Keith Black and had around a thousand horsepower each. Owner/pilot Bill Sterett won the World Championship race in Detroit, his average speed topping 100 mph.

The company’s new “Hydro-Vee” hull design was a deep V hull, using sponsons for lateral stability; it was Chrysler’s first hull, and they made it in six versions from 14 to 23 feet long. The new hull, along with far more attention to electrical wiring and engineering than any other major boat maker, helped Chrysler to achieve a stunning 45.5% of the marine market. The company’s skilled boat designers included Halsey Herreshoff (design engineer for sailboats), Rod Macalpine-Downey, and Dick Gibbs; Macalpine-Downey and Gibbs created smaller sailboats with pirate names (Privateer, Dagger, Mutineer, and Buccaneer).

Hot Boat listed the $1,495 Chrysler Charger (16 foot Hydro-Vee) as having 183 cubic feet of interior space, with a hull weight of 820 pounds. The boat’s steering wheel came from the Dodge Charger. Hot Boat found excellent fit and finish, with fine noise reduction. 0-42 mph came in less than ten seconds; it achieved 5.5 mpg at 2,500 rpm. They called the boat “a well executed and beautifully conceived job” and praised the acceleration from its 96.5 cubic inch engine, while noting that the gas mileage was acceptable. Chrysler boats were far ahead of their time; the foam treatment would not be required by the Coast Guard for years, but did become mandatory.

In 1967, Chrysler brought out Dick Anderson’s Cathedral Hull, which spawned a new full line of boats—all named after cars. Covered in metallic vinyl, these boats included the 16-foot Fury and Sport Fury runabout and bowrider; the best seller, unlike the car world, was the 15 foot Sport Satellite bowrider. In 1968 they added a Buccaneer 18-foot sailboat and a Hydro-Vee based Commando 151, with steering on a fiberglass console; it was targeted at fishermen, with a light 665-pound weight, 15 foot length, and 90-horsepower outboard capacity. A Lone Star 16-footer followed a year later, named after the company they had purchased just a few years ago.

Popular Mechanics praised the Sport Fury’s smooth lines and rounded gunwales, crediting the boat to designer Jack Gampel. The magazine wrote that while it was only 16 feet long, it had the interior space and stability of a 20-footer. The writer tried to get the boat to soak him with lake water, but failed; it was too stable. The test boat was fitted with a Chrysler three-cylinder outboard generating 85 horsepower, which also came in for praise. The only complaints were the steering wheel feel (the wheel itself) and knee space under the console. Perhaps the Buccaneer was more important; also launched in 1968, it was followed by the 15-foot Mutineer. Both were used in One Design Class racing into the 21st century; the Buccaneer was made continuously until 2007 or later, outlasting Chrysler Marine by quite a few years.

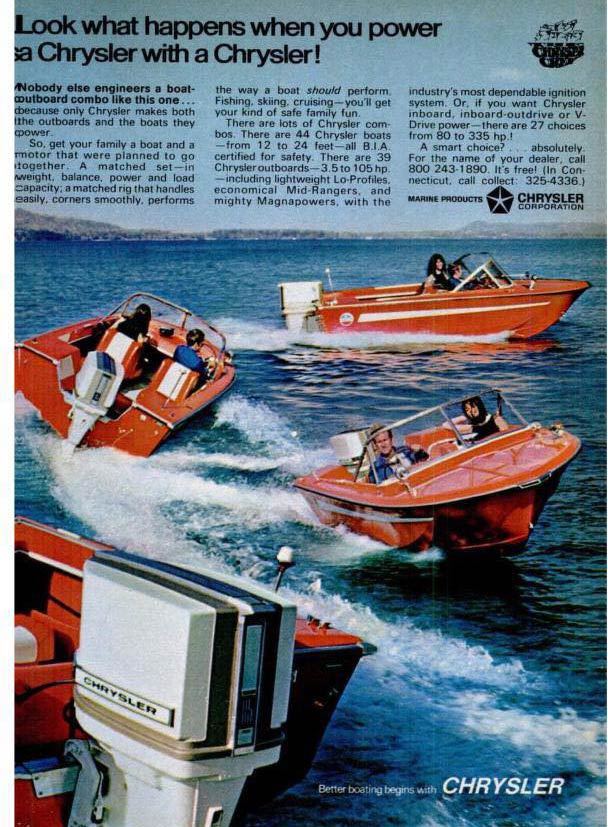

In 1969, Chrysler Boat Corporation had a full lineup of 46 models. They went from 12-foot fishing boats to a 24-foot cruiser, using a modified Nissan diesel as well as their own engines. By this time they had started to add the hull capacity to the boat name, e.g. Chrysler Charger 183 with a capacity of 183 cubic feet; and Chrysler Outboard (the former West Bend) was pumping out 40 different engines, starting at 3.5 horses and ending at 135. Chrysler Canada Outboard Ltd., meanwhile, had a 34,000 square foot outboard plant and a 67,500 square foot boat factory in Barrie, Ontario. Chrysler outboards were sold in 125 countries; the Marine and Industrial Products Operations group had 2,300 employees.

What made a marine engine different? Drop-forged, high-carbon-steel crankshafts; tin-plated, balanced aluminum alloy pistons; forged manganese alloy connecting rods; Stellite-faced valves with positive rotators; alloy cams; special cooling systems; marine alternators; water-jacketed exhaust manifolds; and water-cooled exhaust outlets.

A new hull design for 1969 was “Chrysler Cathedrals,” based on the hydro-vee but with a shorter freeboard and smoother curve from the keel up; side sponsons used cushions of foam for stability and a softer ride. The brochure claimed that the Chrysler Cathedrals “travel on top of the water, gliding over a bow-to-stern cushion of air and water. Her high transom and deep splashwell are ‘dry,’ safety features. And she responds almost instantly to power, planing fast and easily — like a high-powered racing boat. She’s stable and low, with a big, deep splashwell that means storage aplenty.”

Some may have had their doubts about Chrysler’s sudden splash into marine markets, but from buying Lonestar in 1965 to 1969, Chrysler’s market share in the boat industry quadrupled; in 1968 alone, Chrysler Outboard sales increased by 30%, while Chrysler Boat sales went up 23% and the Marine Division overall reported a sales increase of 62%.

Marine sales were handled by three separate subsidiaries, making sailboats and powerboats; inboard engines (typically car engines adapted for marine use); and outboard engines (the former West Bend). Within the boat making subsidiary, power boats and sailboats were different and largely independent entities; it was as though Chrysler had four different boat companies, with three sales-and-service outlets. Dealers would get called on by three different sales reps.

The now-moribund Chrysler Sailing Lizards site claimed that 13 different sailboat models were made in the 1960s and 70s, with several hulls. Factory workers reported that Chrysler put much more care into boat construction than most competitors.

There were several new boats for 1970, with lightweight models from six to 45 horsepower and larger boats in the 16 and 17 foot size (Bass Runner, Conquerer, Courier 231)—and four sailboats to be classic designs, created by Halsey Herreshoff: the C20, C22, C26, and C30. The lineup was now four sailboats (13-18 feet) and 44 power boats (14 to 24 feet). New to the engine lineup were three gasoline V8s and two diesels, a 65-hp four cylinder and a 100-hp six. The new Super Bee engine, based on the car V8, was a 318 cubic inch inboard-outdrive model.

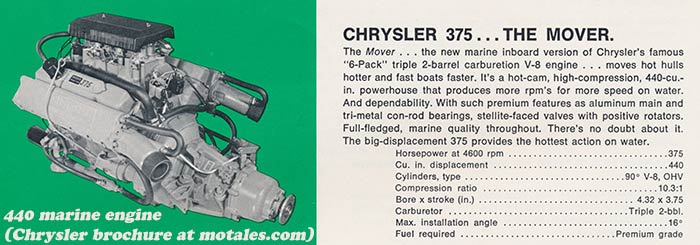

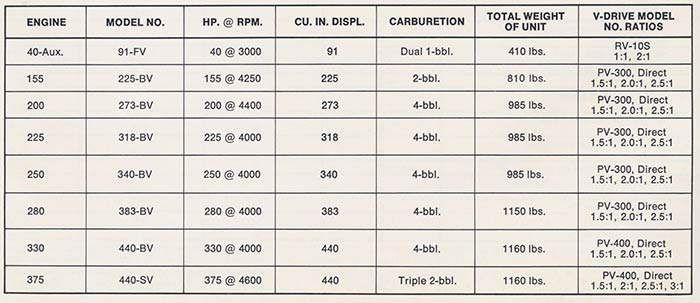

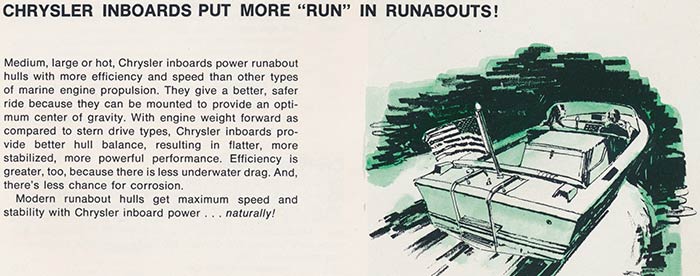

Chrysler advertised their stern-drive inboard/outboard engines as being “Unitized V-Drive;” they moved output from the back to the forward end, transmitting power under the engine to the stern of the boat. Compared against traditional inboard/outboard engines, the company claimed lower pricing and easier installation—with more living space, because the middle of the deck didn’t have to be raised. The unit had less vibration and no vertical leg under water causing drag. The company sold these from 40 to 375 horsepower, in sizes from just 91 to 440 cubic inches; even the 91 cubic inch version had dual one-barrel carburetors, and the slant six version had a two-barrel with 155 horsepower (unlike the ones they were putting in American cars at the time—South American slant six cars had a 155-horsepower two-barrel as well). Note: horsepower figures are gross, not net. The chart below is from a 1971 brochure.

The expansion continued into 1971, with four new fiberglass sport boats, two outboards, and another inboard-outboard; but some older models were dropped, so the offering was 43 powerboats from 12 to 24 feet and three day-sailors from 15 to 18 feet. The new boats were a Courier (154), two Chargers (154 and 186), and a Mutineer. New engines were a 130-horse high end model and a 150-horse racing engine. To address pollution, which was becoming a fairly popular issue among the general public, Chrysler started taking excess fuel, atomizing it, and feeding it back into the engine to end fuel spillage.

In 1971, there was 10 inboard-outboard engines, ranging from 130 to 330 horsepower, 9 inboards, ranging from 40 to 375 horsepower, and 6, two and four-cycle diesels, ranging from 65 to 325 horsepower. The division did well in 1971; but they had another record year in 1972, with an 18% sales increase over 1971.

Next, Chrysler redesigned its 14 to 16 foot cathedral-hull boats, while launching a high-performance sport boat, 18.5 feet long, with a choice of jet drive and inboard/outboard power. A new Professional version of the 16-foot Bass Runner was launched for inland water fishermen, too; this had side-console steering, a cushioned seat with a live well, long port-side locking compartment (set up with fishing rod mounts), adjustable swivel fishing chairs with armrests, and pile carpeting.

The company now had 28 fiberglass boats from 14 to 23 feet in length, and three sailboats from 15 to 18 feet. There was also news on the outboard front, with eight new engines from 25 to 30 horsepower for fishing and cruising; the outboard range had 57 models with up to 150 horsepower, including a new jet propulsion setup, while the Marine Division had 22 engines—15 gasoline powered (40-375 hp) and 7 diesels (65-275 hp).

In 1973, buyers could get a new 14-foot Valiant runabout on a raised-deck cathedral hull, with a longer, deeper cockpit. A new Conqueror S-III sport boat had an 18.5 foot hull—and buyers could get the 340 cubic inch Super Bee III jet or an inside-out V8 engine; these boats could beat 50 mph, aided by full-length lifting strakes. The Marine group posted yet another record year, with revenue rising by 8.2% from 1972.

1974 saw a new deep-V Conquerer 105, which Chrysler claimed was the only boat designed for a specific outboard (the Chrysler 105). A shallow-V Conquerer and hydro-V Carvel III joined the roster as well. For 1975, building on the most popular Chrysler boat of 1974—the Conquerer 105—the company launched the 17-foot Conquerer 135, and in 1976, the same name adorned a 21-footer which could have jet power or a V8 stern drive.

The outboard line was restyled in 1977; the company also launched a new deep-V cruiser and 20-foot sailboat, but troubles in Chrysler’s main business, automotive, led the executives to consolidate the group in 1978. Likewise, because cars had already lost their 440 engines, the marine division couldn’t sell them; they stocked up to work with existing demand, which would last until 1981, but that was the end of their highest-performance engines.

In this year, as well, Chrysler put two new Sea-Vee premium boats into production, 22 and 25 footers. They also created a 16-foot performance hull boat (“Fin & Fun”) and a trio of Funster boats. The Marine and Industrial division offices moved to Beaver Dam, Wisconsin.

The 1978 reorganization coincided with Lee Iacocca’s arrival at Chrysler. He told executives how much the company was losing every day. Many of the people in sales and engineering were laid off (and many of them were eagerly snatched up by other companies); many projects were scrapped to save cash. Those who stayed loyal to Chrysler, resisting the headhunters’ calls, could have their salary cut and their benefits slashed. The consolation for many was that the cuts, which may have been p to 50% of costs, ran all the way to the executive offices; everyone was sacrificing.

The final year of Chrysler Marine was 1979; in this year, the first fully-rigged bowrider was launched, with a color coordinated boat and motor; and a new 15-foot Fin & Fun joined the 16-footer. All the boats used rack and pinion steering.

During these final years, 1978 and 1979, the general public knew Chrysler was in trouble and might not survive. The independent dealerships and distributors took over advertising and marketing, even splitting up attendance at boat shows so the public would see Chrysler there. Even so, the division appears to have been profitable (no information was provided in annual reports; in 1978, non-automotive posted a $40 million gain, but that included M-1 tanks) and may have kept going indefinitely, with advanced boats and a loyal following.

Under orders from the US government (as part of loan guarantees), Chrysler had to sell off the boat business. A group of former Chrysler executives created Texas Marine International (TMI) and bought the boat business in January 1980; but the company failed fairly quickly, due more to a crashing boat market than anything else. Wellcraft bought some of their sailboats and some of the power boats; the rest of the sailboats went to six other companies. One, Sportco, made Chrysler sailboats at least as far as 1992; at least one boat stayed in production into 2007.

With the sale of the actual boat building business, the outboards division became part of Amplex, Chrysler’s longstanding chemical and sintered-metal division.

The stern drives went to Bayliner Boats in 1983; the outboards went to Force Outboards (part of U.S. Marine) in 1984, and eventually ended up as part of Mercury Marine parent Brunswick Corporation. The outboard division, the former West Bend, was still coining cash, and was particularly attractive because the Hartford plant, dealer setup, engineering team, and such were all one unit, easy to split from Chrysler itself. It may have been sold even earlier, but there was a question of whether to sell the inboard business as well.

That left inboard marine engines as Chrysler’s sole marine product, made and sold by the Marine/Industrial Engines Group. The company unveiled a 340 horsepower marine V8 at the 1986 New York Boat Show, but chances are that boat builders did not want to rely on Chrysler for engines.

According to J.P. Joans, Chrysler sold most of its inboard engine business to Canadian firm Indmar in 1989 or 1990. The company continued to sell the marine-fitted 340 V8, and in May 1991, started jointly developing a two-stroke engine with Mercury Marine.

Chrysler had been trying to develop a two-stroke engine for cars, and had been looking at valved, ported, and hybrid valved-and-ported designs, hoping to have something for a future city car. Mercury, on the other hand, needed to upgrade their own engines to meet new pollution standards. The project did not last long, and in the end, the two companies parted ways; Chrysler had discovered they could not get emissions of oxides of nitrogen to the legal limits, ending their interest. They also shut down the remains of their marine engine business, including the 340, in 1993, as they focused on rebuilding all of their car lines.

Eventually, the company went back into the business of selling engines for boats, with the aluminum V-10 Viper engine; its torque was similar to that of a light truck diesel. Ilmor Marine, which was helping to update the V10 in the Dodge Viper, started working on a marine variant, dubbed the MV-10. This was released, with 550 horsepower, in 2005, as the MV10 625; and in 2006, as the MV7-10; followed by two 2009 engines which met EU and California emissions regs, the MV10 650 and 725. Using these engines, Ilmor won five world powerboat racing championships.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos