Through the 1980s, it became increasingly obvious that Chrysler had fallen behind Japanese automakers in many ways that had nothing to do with car engineering. Using American workers, and in some cases former trouble-prone American factories, Japanese companies were able to have much higher quality and lower costs. One team at Chrysler was sent out to discover why—and they came back with, among other ideas, flexible manufacturing.

Flexible manufacturing, pioneered by Chrysler in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, was a set of practices in engineering and manufacturing meant to allow the same assembly line to make different vehicles, without changing tooling. By 1995, Chrysler could make completely different vehicles on the same line, without delays. They could pilot one vehicle while producing three others.

The Chrysler team visited Mitsubishi factories, which they had full access to as a part owner of the company, and sought and read literature on Toyota, Honda, and others. When they reported back in late 1989, they focused on why Japanese companies easily shifted from one generation of a car to the next while American automakers stumbled. There were a few differences:

The end result was that Chrysler’s changeovers took a great deal of time, and older equipment could hurt quality or productivity long before a new model came around. They did have some gains from prior process changes and modular framing, including a two-week downtime when they added the Y-body to the C-body at the Belvidere plant. The flex manufacturing approach, imbued with long-term thinking and systems design, first launched with the Grand Cherokee at Jefferson North (a mid-1992 model); it was then part of every new car launch. When assembly lines for existing vehicles stopped, the factories were stripped out, and the extra stations, flexible robots, and such were added. The new carriers were “pallets” or platforms on which the bodies rested, so the actual dimensions of the vehicle were less important; a Fiat 500 could follow a Dodge Journey.

Chrysler’s setup, like those of Toyota and Mitsubishi, used special robots and computers. Robots generally had tooling or spot welders on the end of their “arms;” with flex, they could quickly swap the tooling or welders between cars, or simply apply their arms with different motions, welding in different places. In paint shops, the same robot arms were acted differently to match the vehicle in front of them.

The main requirement was simply that both types of car fit on the line and within the space envelope needed by the equipment. Chrysler plants were built to make two completely different cars at once, interchangeably, with a third different vehicle being piloted as well; later they went to being able to make four different cars at once, though this was never done.

The setup required flexible robots and computer networks, which is one reason it took so long to arrive. Before that, flexible plants did exist, but they had humans making various types of cars, and mistakes were fairly common, e.g. having Dodge name badges on Plymouths, or mismatching mirrors. By the 1990s, Chrysler was able to tap fast computer networks, as well as computer readable barcodes and even radio identification (RFID) tags.

Vehicles were moved from station to station by carriers, which usually had four points supporting the body as it was built (once the tires were installed, the vehicles tended to go onto a flat track). Keeping the same points on different bodies allowed for a good deal of variation.

The flexible body shops had no huge fixtures and jigs engineered to create a single part or vehicle. In the Belvidere plant, which made the related Compass, Patriot, and Caliber—based on the same essentials, but in very different forms, as a sedan, wagon, and boxy-like SUV—the same robot could easily assembly and weld a part for each of the three, one after the other... and a fourth part for a completely different vehicle as well.

Chrysler photo: building a 2013 Dodge Dart on the same line as the old Jeep Patriot

They could change to a completely different model in a week or less, without dropping production by more than half in either model. The company estimated all this would cut a new model’s capital expenses by 20% to 40%, and cut future changeovers by half—or 70-80% for completely different models—while increasing quality. They would, though, need a more disciplined engineering process; engineering without process changes; and a smaller, core group of more-included suppliers.

Platforms were redefined as dimensions shared between different “top hats” (upper bodies) and collections of hard chassis parts. That provided the opportunity to have far more variation between cars made on the same line, again without having to stop to retool. While earlier platforms had been defined by some possibly odd measures, like the tilt of the windshield, they now only represented hard points and space.

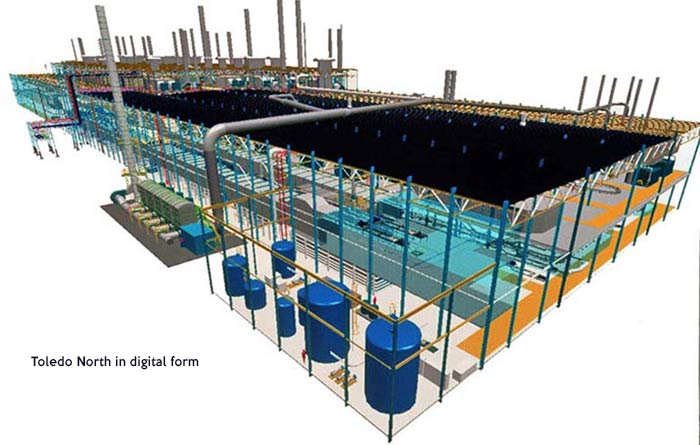

Any changes or new models could be set up by downloading new software to the robots, without fixture rework and replacement. Robot motions were simulated before this step; the company even had digital models of its lines to test for interactions between machines.

Flex manufacturing was never fully used by Chrysler, but they did have a few examples—the Charger and 300 sedans, Challenger coupe, and Magnum wagon were all made on the same lines. The Grand Cherokee and Commander shared an assembly line, too. So did the aforementioned Compass, Patriot, and Caliber. And, later on, the Pacifica crossover shared a line with the Caravan and Town & Country minivans.

In theory, this meant that the company could make many different versions of the same car without production line delays—and at much lower tooling costs. This made it easier to reach the magic 100,000 breakeven point on the same basic car, by having different variants. The Compass, Caliber, and Patriot were a decent example of this—while none were especially popular, as the years went on, one model or another would tend to be far more popular. Before flex, it would not have been practical to make all three versions; and they couldn’t have easily switched from one to the other with sales. They certainly couldn’t have started building Dodge Darts on the same line.

Vehicles could (like the 300M, LHS, and other LH cars) have different wheelbases; they could have different numbers of doors; they could have different forms.

The investment in this technology took place over many years, and was pushed by Chrysler after its first uses to be more and more flexible—even if Daimler, and then Fiat, never chose to take full advantage of it, because it would have meant engineering more variants of each vehicle (as a Mazda 3, for example, is sold as a compact sedan, a compact hatch, and two sizes of crossover). Neither Daimler, nor Fiat, nor Stellantis wanted to make those investments, though by 2026 they may come to fruition.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos