Chrysler had a fairly simple strategy from the 1950s into the late 1970s. Plymouth and Dodge both competed with Chevrolet, even though Dodge sold at a premium to Plymouth; when they had similar bodies, Dodge usually had a couple of extra (and very costly) inches of wheelbase to support the price increase. Ordinary buyers were confused by this; most who know Dodge was a premium brand (compared with Plymouth) think it was meant to compete against Pontiac.

Once DeSoto was gone, Chrysler itself went up against Buick, Oldsmobile, and Pontiac. Imperial didn’t really compete, Burt said, but “was a car for dealers’ wives and their wealthy friends.” (It may well have continued largely because executives liked to drive it, too, and it tended to get excellent reviews in the automotive press.)

The Imperial’s profit margin in manufacturing must have been immense, but it was swamped by engineering and tooling costs which were distributed across a small number of cars each year—a few thousand would be a good year.

Young accountant Lynn Townsend was put in control of Chrysler in 1962; he set up the model of Plymouth competing with Chevrolet and Ford, Dodge competing with Pontiac, and Chrysler going up against Buick and Oldsmobile, with Imperial at the Cadillac/Lincoln level. When Burt Bouwkamp was appointed head of product planning for Dodge cars in 1964, Townsend met him one-on-one and told him to “think Pontiac.”

Dealers didn’t buy it. Dodge dealers (and executives) still wanted to go against Chevrolet, where the volume was. That positioning didn’t give Dodge high profits, but did hurt their own sibling, Plymouth. Dodge had even argued for its own version of the Valiant, originally seen as a brand below Plymouth.

Whether Dodge was paired against Chevrolet or Pontiac, their competitor, GM, set their standards and decided what cars they would sell and how much they would charge. The strategy was the complete opposite of the one which had made Chrysler successful in the first place: ignoring existing classes. Chrysler and Plymouth had both combined the technology (in Chrysler’s case, the performance) found on luxury cars with a relatively downmarket body. Both had been successful by being a bit pricier than direct competitors, while delivering far more.

Starting in 1973-74, designers and planners worked on making minivans; but the program was rejected by upper management because GM and Ford didn’t have one. That confirmed Burt Bouwkamp’s view, which remained firm till his death in 2022, that Chrysler’s “strategy” was “to get 15 to 20% of market segments established by GM and Ford.”

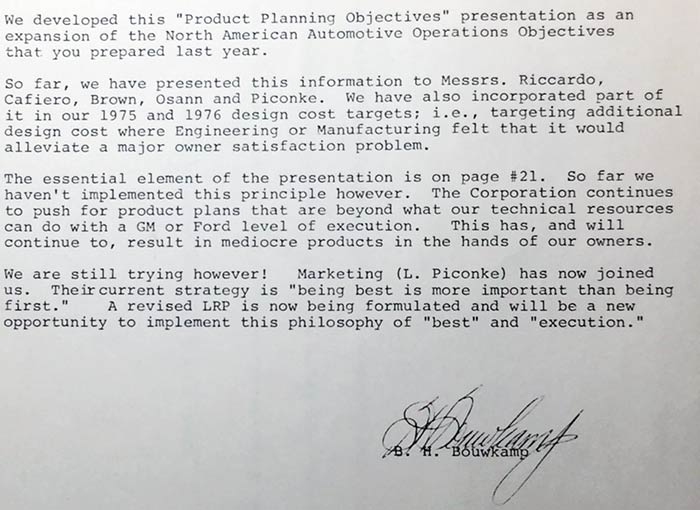

Product planners, engineers, and designers tried to convince Chrysler leaders to focus on producing fewer but better cars. They meant to combine their compact and midsized sedans, which were not far apart in size, into one series, for example. That means that the still-unstarted Aspen and Volare would replace the Coronet, Belvedere, Valiant, Duster, Dart, and such. Burt Bouwkamp, as head of product planning, wrote the introductory memo to the report and presentation, dated April 9, 1973.

They set a new long-range goal: producing cars with a “level of appearance and functional execution that will result in competitive and profitable products that meet owner expectations for quality, reliability, and cost of ownership.” This would attack Chrysler’s lower-than-average owner loyalty of the time, provide economies of scale, and recognize the company’s smaller resources.

This group’s strategy recognized future mandates—more engineering would be needed as safety and emissions rules took effect—as well as internal resources, and the inability for a smaller company to match the giant GM car-for-car, truck-for-truck.

Sales Management objected, though, insisting that Chrysler had to have both compact and midsized models to directly compete with Chevrolet and Ford. In a company that once prided itself on putting engineering first, the combination of dealerships and Sales Management was enough to stop Boukwamp’s strategic plan from taking effect. Some of the issue may also have been some instability and personality conflicts in the executive offices, and despite the company’s roller-coaster past, some degree of complacency.

Bouwkamp and his group turned out to be right, in retrospect. Fuel crises dropped large car sales to almost zero; buyers flocked to compact cars (such as the Volare) and imported subcompacts. Chrysler leaders still led the salespeople push them forward, creating the R bodies, which were just slightly larger than the midsized B bodies, to replace their biggest cars. That move wasted a great deal of money, the rush job hurt the company’s reputation, and the R bodies quickly disappeared. They may well have bankrupted the company, spending resources they didn’t have and distracting from serious solutions—the L and K bodies.

Before long, Chrysler ended up selling just one kind of rear wheel drive car—based on the Aspen and Volare.

New chief executive Lee Iacocca finally swept away the sales group’s insistence on matching GM and Ford car-for-car. He arbitrarily decreed Dodge the sporty brand, though Plymouth had great success not long before with the Duster and Road Runner. Hence Dodge got the Daytona, the sportiest Mitsubishi (Stealth), and exclusive use of the hottest engines of the day (the 2.2 Turbo III and Turbo IV). When the time came to do an all-out sports car, despite being barebones, it went to Dodge. Chrysler and Plymouth essentially shared a softer ride, but Chrysler got more features and chrome, and Plymouth sometimes only had the lower-end engines.

Had the leaders of Chrysler Corporation listened to Burt Bouwkamp and a large number of memo co-signers, they may well have avoided bankruptcy and kept control of SIMCA. It would be a very different company today—but it may still have faltered and fallen, and would probably not have purchased AMC. That road of history is full of possibilities we can never know.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos