Today, and for the past few decades, Dodge has been associated in the public mind with trucks—even though Ram is no longer part of Dodge, and the Dodge Brothers themselves never built a truck.

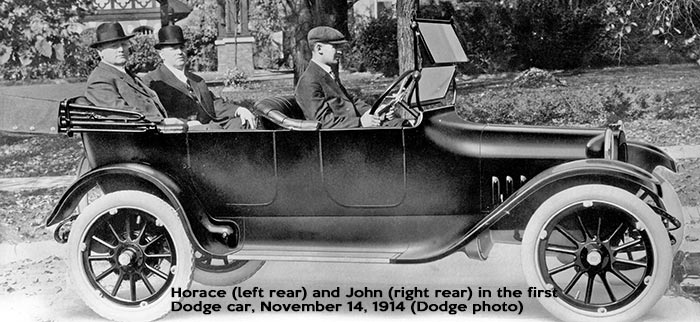

There were two Dodge brothers, John and Horace. They were highly successful even before entering the auto trade; their first major automotive contract was with Random Olds, for the first truly mass-produced (assembly line) car. Their fortune was multiplied by working with Henry Ford, financing Ford’s third attempt at making a car (and re-engineering it quite a bit to make it work properly). They provided their labor and expertise, along with the services of their plant, in exchange for money and a hefty chunk of the new company.

Eventually, disgusted by Ford’s greed, low engineering standards, and abusive industrial practices—not to mention the likelihood that Ford would build his own facilities and leave Dodge Brothers out of the picutre—the Dodges left Ford to build their own car. The Dodge Brothers car was well-engineered; it sold at a premium, and was made by workers who were well paid and, by the standards of the day, very well treated. The only things Ford and Dodge Brothers had in common were mass production and (rather different) four-cylinder engines.

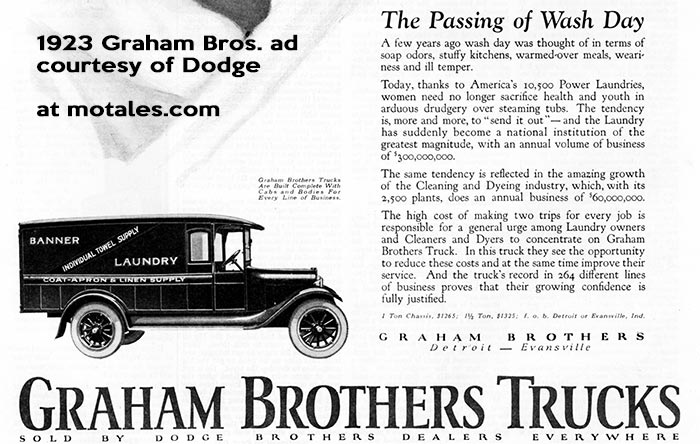

Meanwhile, the three Graham brothers—Ray, Robert, and Joseph—had started a glass factory in Evansville, Indiana, eventually selling it to Ford. They started making truck bodies in 1916; their major innovation came in 1919, with the “Truck-builder.” This was a frame, body, cab, and gear drive, on top of which customers could build their own trucks. This developed into their own fully built truck, which was, like the Truck-builder, a hit.

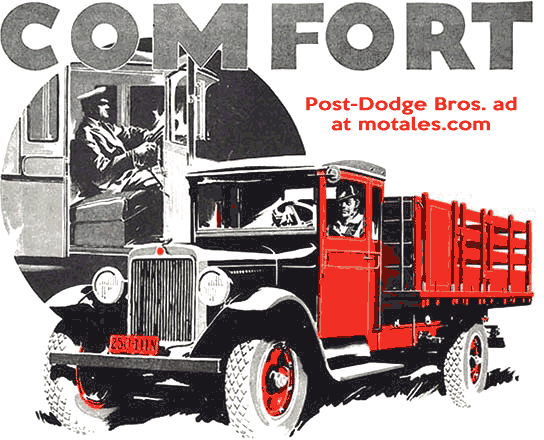

After the Dodge brothers died, Frederick Haynes was put in charge of their company. He reached out to Graham Brothers Trucks, seeking to have Graham make trucks with Dodge Bros. powertrains, for sale through Dodge Bros. dealers. They sold one-ton and one-and-a-half-ton pickups first, using Dodge Brothers four-cylinder engines. Graham now had plants in both Evansville (where they had founded their glass factory) and Stockton, California.

Graham Brothers started selling the trucks in 1921, using a 13,000 square foot facility; in 1925 they bought a 250,000 square foot plant (purchased from Dodge), with a conveyor-type assembly line.

In 1925, Dodge Bros. bought a majority interest in Graham; the next year, they bought the rest. As a result, Robert Graham was put in charge of sales for all of Dodge Brothers; Ray Graham was made general manager; and Joseph Graham was put in charge of manufacturing. The Grahams got their new jobs in 1926 and left them in 1927, before Chrysler bought Dodge Brothers (1928).

One may ask why the Graham brothers left Dodge Brothers so quickly; the answer would be the Paige Company of Indiana, which they bought in 1927 for $840,000, along with the Paige-Detroit Company for $3.5 million. They changed the name to Graham-Paige with the 1928 cars, made with six and eight cylinder in-line engines; cars made after 1930 used the Graham name. They kept the Paige name for the company itself and, ironically, for commercial trucks. (Joseph was the president, Robert was executive vice president, and Ray was the treasurer.)

The first new cars were in the middle of the market, priced low enough to be popular but high enough to be far away from Ford. Graham-Paige was quite a success at first, selling 73,195 cars in 1928 and 77,000 cars in 1929. An example of their product line was the Model 827, which featured a 120-bhp straight-eight, using a 127 inch wheelbase and a coupe body. A Special Eight Sedan version was released the next year, cutting the power a bit to favor gas mileage.

The brothers chose to expand at perhaps the wrong time, building new plants in Michigan and Florida in 1929; the Depression slammed their sales, but they kept going, dropping prices as needed to keep sales going.

The early days of Graham-Paige were impressive, even if they had a hard time competing for sales during the Depression; their styling was beautiful and copied by other companies, and their expertise in engineering was almost a match for industry leader Chrysler Corporation. Their lineup ran from economy car to supercharged luxury cars with custom bodies—which were somehow reasonably priced; they pioneered the streamlining look and made it seem natural, which the later Airflow failed to do.

Most of the 1930 Grahams had aluminum pistons, four-speed transmissions, and rubber-cushioned chassis, an impressive set of features; they had two six-cylinder cars with the straight-eights, starting at $695. They also set a world record for endurance with a straight-eight model. 1931 cars had new all-steel frames (eights only). Superchargers came to the six-cylinders in 1934; they were driven by the water pump shaft, producing 116 bhp.

In 1936, they shared the cost of building a new Reo body with Hupp; this was made into 1937, when they turned down an offer to build the Cord 810/812 with Hupp, using tools and dies acquired from Cord by a third party. Hupp chose to go it alone, converting it into the Hupp Skylark, which proved to be disastrous. Their version was converted to rear wheel drive, with a ten inch shorter front end, and other changes. Hupp ran out of money trying to convert it to use a one-piece roof (Cord had a seven-piece roof which required a great deal of labor)—two years after the project started.

Graham and Hupp tried sharing costs to finish the project, using a Hupp six-cylinder and selling it as both the Hupp Skylark and Graham Hollywood. Finally, in 1940, they succeeded, making a small number of Cord-derived cars for $1,250 each—discounted to $1,045 in 1941. This last Graham car included the 116 bhp supercharged six; then Graham stopped making cars and started working through what would become $20 million of defense contracts.

Two years into the war, the sole surviving Graham brother was Joseph. He sold his stock to Joseph W. Frazer and a group of other investors, and Frazer took over as the lead executive.

After the end of the war, Frazer proposed making two lines of cars—a low-priced, rear-engined Graham, and a medium-priced, more-conventional Frazer. Since Graham-Paige did not have the resources for twin carlines, he worked with famed industrialist Henry J. Kaiser; the result was the new Kaiser-Frazer, which purchased Graham’s car business, intellectual property, and plants in 1947. Graham’s Warren Avenue plant in Dearborn went to Chrysler; it made bodies for DeSoto from 1950 to 1959, along with the first Hemi V8 engines, and was then converted to making Imperials, though that only lasted for a couple of years.

Graham-Paige, without any cars or any other reason for existing, dropped the term “Motors” from its name and became an investment corporation. Graham-Paige ran Madison Square Garden and several sports teams, in 1962 changing its name to “Madison Square Garden Corporation.” With that move, its founders’ names joined its cars and trucks in leaving active life and existing solely in museums, books, garages, and the odd web page.

Key sources: Allpar; contemporary advertising; J.L. Beardsley’s Graham: The Might-Have-Been Car, Car Life, December 1966

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky