Maxwell Motors’ 1924 Chrysler car was quite advanced. The 1904 Maxwell had also been fairly advanced, but it was mainly created by a single person and belonged firmly in the brass era. The Chrysler was far more modern, with a self-starter, hydraulic brakes, high compression engine, forced lubrication and cooling, and a top speed of 70 mph—far higher than most cars sold at the time. It was, in short, further ahead of the game than the Maxwell had been.

The new Chrysler car had been created by a team of 18 people from Studebaker who had moved together to Willys in 1920, led by Frederick Zeder, Owen Skelton, and Carl Breer. Tobe Couture, one member of that team, wrote that Zeder ordered a new car that used as much of the tooling for a newly abandoned Willys car as possible. They set up a drafting room at the Beachwood Hotel at Summit, New Jersey and built up the car from there.

Walter P. Chrysler, then leading Willys New Jersey’s turnaround, planned to build the new car under his own name, but John North Willys threw the company into receivership, W.C. Durant bought the Elizabeth plant at auction, and the team from Studebaker set itself up as the Zeder-Skelton-Breer Engineering Company in nearby Newark.

They rented their old engineering facilities at the Elizabeth plant for $100 per month and took in outside jobs, their main client being Durant himself. Couture added, “We thought that [their 25 people] was a large group... at no time did we stop perfecting our ‘Chrysler 6.’ Even though we had lost our original car to Mr. Durant, with all drawings and specifications, we again went to work on another car from the ground up... ”

Walter Chrysler returned to Elizabeth in April 1923 to see the Zeder-Skelton-Breer six-cylinder running on the dynamometer (“dyno,” or power measuring machine). Couture remembered, “He was so impressed with the smoothness and performance that he immediately gave orders to proceed with the final design, as he was almost certain this car would be built in the Chalmers plant in Detroit.” Chrysler also demanded five experimental cars by September 1, 1923—less than five months away.

The engineers settled into the second floor of Chalmers’ old Building Nine on Jefferson Avenue, Detroit, in June 1923, eleven miles from Maxwell’s engineering department in Highland Park. Couture convinced Chrysler to wait until they had four-wheel hydraulic brakes, rather than the usual two-wheel mechanical brakes. Carl Breer and his group had been working to make the Lockheed hydraulic brake design work; as originally concived, it almost worked, and then only under ideal conditions. After Breer’s group changed just about every aspect of it, Chrysler assigned the patents to Lockheed so others would use them; but the 1924 Chrysler was one of the very first cars to have four-wheel hydraulic brakes. It was almost worth the four-year wait for that and the high compression engine, which together helped push the Chrysler past the brass era.

The original 1924 Chrysler started production in January 1924, in six body styles, with three more bodies by the end of the year. Weight ranged from 2,730 to 3,225 lb; all had a three-speed manual transmission, six-cylinder engine, and pricing from $1,335 to $3,725, paralleling Buick. All but two cost less than $1,900.

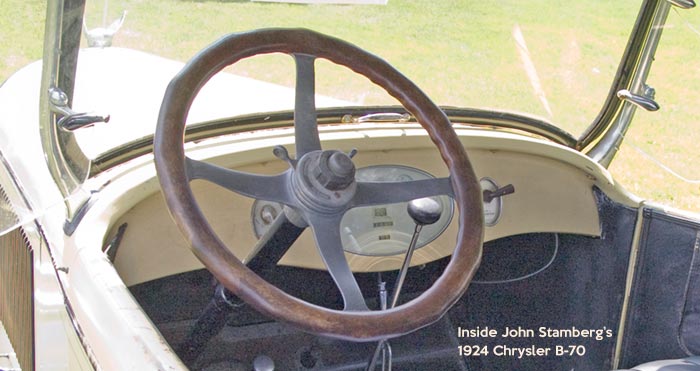

The car was dubbed the model B-70, the model A being the car created at Willys. The 70 referred to the top speed; the car could, from the factory, reach 70-75 mph (the digital speedometer read up to 80). It was a major triumph, and only five mph slower than the eight-cylinder 1924 Packard, a much more expensive car.

| 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Sales # | 79,144 | 137,688 | 170,392 | 192,083 | 360,399 |

| Sales $ | $137 mm | $163 mm | $172 mm | $315 mm | |

| Profit | $17 mm | $15 mm | $19 mm | $31 mm |

Sales above include Maxwell and/or Plymouth where relevant.

The “Good Maxwell,” already dramatically improved by the Zeder-Skelton-Breer team, was already profitable. Reportedly, in 1924, Maxwell made 33,000 Chrysler cars—a record for first-year production—as well as many Maxwells.

In 1925, Chrysler Corporation was created as a holding company; it bought Maxwell, Chalmers, and Zeder-Skelton-Breer. Chrysler reinvested $15 million of its income in 1925, $6 million in 1926, $10 million in 1927, and $19 million in 1928. They ended the Maxwell name at the end of 1926, reintroducing it as the Chrysler Four—which only lasted for two years. With more modifications, it became the 1928 Plymouth. Chrysler also purchased Dodge Brothers, which was three times its size, in 1928. Chrysler was third place in the domestic auto industry in that year.

Aside from the rebadged Maxwells sold in 1927, Chryslers were exclusively straight-sixes until 1930, when a straight-eight was added. That engine was a true achievement—the first eight cylinder under $1,000 in 1933 (they started at $895 F.O.B. Detroit). The top of the line, dubbed Imperial, was just $1,275 in that year.

The 1924 Dodge Brothers car had just made a single rear brake light standard, matching the 1924 Chrysler; but the “Dodge” only had 35 hp four-cylinders, with dual-wheel mechanical brakes which were not especially effective (braking, like acceleration, was largely done with gearing). Dodge Brothers made 193,861 cars in 1924, around two and a half times all the Maxwells and Chryslers made that year; but their prices were far lower, though, at $865 to $1,545 (not counting custom bodies), with most of their cars at roughly $1,000.

The Chrysler’s attractive, functional styling has been credited to Oliver Clark, one of the 18 people in the original team. He also created the Chrysler emblem, set up the Art & Colour Section in 1928, and became Chrysler’s chief body engineer in 1933.

Clark styled the ornamental radiator cap, basing it on a Viking cap, and using Mercury wings to symbolize speed; there was space for a temperature gauge to fit between the wings, as owners of other cars replaced their caps with aftermarket models to add a thermometer. Chrysler, though, added a temperature gauge to the dashboard instead.

All the gauges were clustered in one place, under a reflection-resisting contoured sheet of glass. This was one area where you could see that a Chrysler was not, say, a Packard; the Packard interiors were far more plush, with bigger gauges, nicer woods, and so on.

The choke was a large switch on the right side of the dashboard, within reach and easy to operate with gloves on.

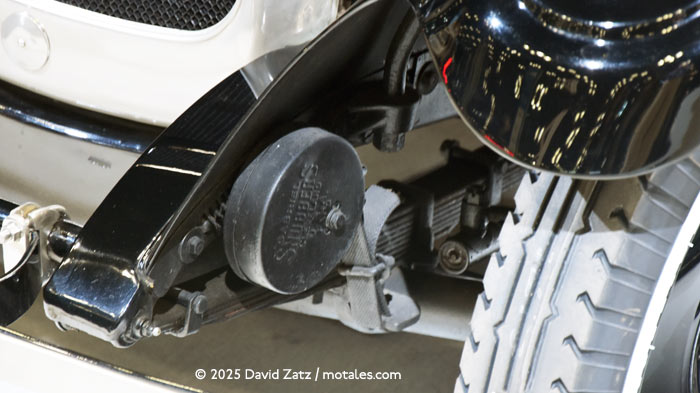

Features like this had never been offered in a mediumpriced car before, and the 32,000 first-year record sales substantiated the tremendous appeal of the first Chrysler car. The main change for 1925 was a new vibration dampener, frictiondriven by a hub on the crankshaft, for smoother performance; in 1925 or 1926, the company leaped forward with rubber engine mountings and rubber spring shackles, which dramatically cut down on vibration passed to the passengers.

The car itself weighed 2,700 lb (touring model), and could come close to 75 miles per hour, quite good for the time. The new Chryslers were not especially large, with a wheelbase just short of 113 inches, but it had a high power-to-weight ratio; styling cleverly made it look like a larger car, with tires scaled down to match the smaller body (the 1924 Chrysler used 29 x 4.5 tires while most competitors used 31 x 4 tires; in 1925, with public acceptance assured, Chrysler switched to 30 x 5.7 tires, which must have improved cornering and braking considerably). The state of the art brakes were far easier to use than the mechanical brakes in most cars — and their superior equalization meant straighter stops.

Chrysler and Maxwell sold 137,666 cars in 1925, from the $895 Maxwell Four Touring to the $2065 Chrysler Six Sedan. In 1926, with the Maxwell Four gone, they sold 170,392 cars; there were now four Chrysler models, the 58, 60, 70, and bored-and-stroked Imperial 80, all named after their top speeds. The Chrysler 58 was essentially an improved Maxwell (which would later be sold as the Plymouth), and sold for $845; the most expensive car was now the Imperial seven-passenger limousine sedan at $3,595. The situation remained similar until 1928, when DeSoto, Dodge Brothers, Plymouth, and Graham Brothers were added.

Front suspension with snubber

For 1925, the price went up by $60, while the weight went down by 150 lb; the tires were bigger and the engine rated slightly differently but the model, Chrysler 70, was unchanged. After 1925, the wheelbase was listed as exactly 112 inches, though whether it was changed or simply rounded down is unclear. For 1927, the Chrysler 60 ran on a 109” wheelbase, barely longer than the Maxwell/Chrysler 50/Plymouth’s 106”, and weighed in at just 2,690 lb - while the 70 went up to 3,090 lb (these figures are for closed cars and are heavier than the 1924-25 figures); the 60 used a 54 horsepower version of the Chrysler Six, with a smaller bore and stroke (3 x 4.25).

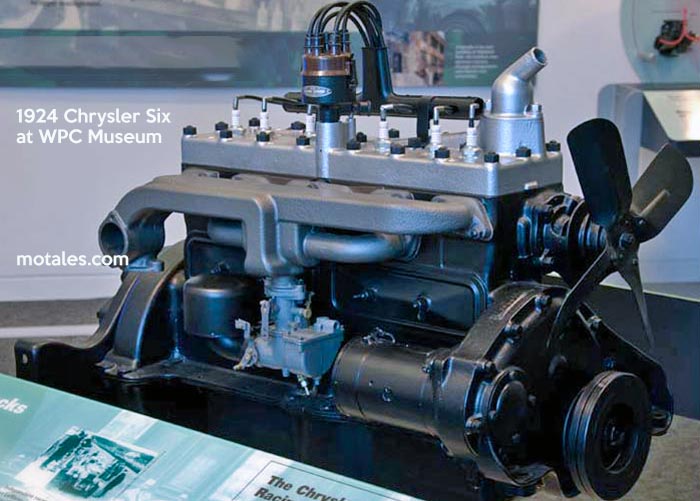

The Chrysler six was fairly revolutionary, the first mass production engine with high compression engine; it also had an intake air cleaner and, an industry first, a replaceable oil filter. This oil filter had a sight feed for a few years, before the engine was a full-flow design. It had been invented by a man named Sweetland. The air cleaner was still a relatively new device; Chrysler used a rotating, self-cleaning dry unit from the United Air Cleaner Company.

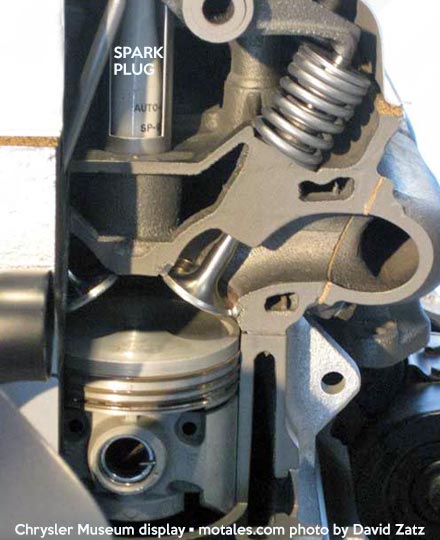

Engineer Pete Hagenbuch said in the 21st century that the Chrysler had two features they advertised quite a bit; one was the brakes, and the other was their 5:1 compression ratio. “That was huge when everybody else had 4:1.” Much of their advance followed Ricardo’s work on L-head combustion chambers. Usually, L-heads had the spark plug on top of the valves, as far out as possible, “making it almost impossible not to have knock.” Chrysler’s team centralized it. Later, Hagenbuch noted, “We found in our wedge chamber overhead valve engines, the squish is very important. It gives you lots of mechanical octane numbers. So, they were way ahead of their time.”

A great deal of thought went into preventing detonation. Breer wrote, “the rapid progression of the flame over the piston area... could be slowed by bringing as much area of the cylinder head down close as possible to the piston at the top of its stroke. Then we would rib the adjacent head surface to offer more cooling area, thus slowing the rapid flame travel...”

They were able to run the engine at full power (3,000 rpm) for fifty hours, then quite a good run—and that was just the start. They adapted an experimental two-piece tappet from Wilcox-Rich to reduce scuffing. Numerous test heads were tried out, before the settled on the flat-head design. The Chrysler had “an authentic 68 hp” at with 50-55 octane fuel and a 4.7:1 compression ratio. (At launch, they listed 70 horsepower at 3,500 rpm; from 1925 to 1927, it was listed at 68 @ 3,000.) That can be compared to the Maxwell’s 28 horsepower. The Imperial was bored out from 4.75 inches to 5.00 inches, yielding 92 hp.

One interesting marketing piece was a 1925 “interview” with Walter Chrysler:

I have been convinced for years that the public has a definite idea of a real quality light car—one not extravagently large and heavy for one or two people, but adequately roomy for five; economical to own and to operate. And, above all, real quality from headlights to tail-light.

My conception of an ideal quality light car, is that of scores of thousands, whose requirements are practical, not visionary. For them, I saw a car with the power of a super-dreadnaught, but with the endurance and speed of a fleet scout cruiser. What these drivers want is, briefly, this —

- A perfectly balanced six-cylinder motor with top speed of over 70 miles an hour—not because they want to drive at that rate,but to insure quick get-away, flashing pick-up, power to conquer any hill, and for the steady pull at low speeds

- A small-bore power plant; first for fine performance, and second for gasoline and oil economy.

- Simplicity and accessibility throughout

- Lots of room. I mean wide doors, deep comfortable seats, ample leg-room.

- Real comfort; long soft springs; extra size tires, deep overstuffed cushions.

- Driving convenience and ease that will let a woman drive in comfort for long distances or through heavy traffic.

- Light weight, so that a single passenger doesn't feel he is paying to haul a private Pullman; yet without squeaks, rattles, or flimsiness.

- Wheelbase built to fit into an ordinary parking space and to insure quick and a well on rutted road or a cobble-stone street.

- Quality materials and workmanship to give long life and constantly good service, instead of a job built to a fit price.

- Beauty that speaks for itself, and good taste that is self-evident

- Complete modern equipment built into the car, not hung on it merely as an after-thought.

The plan has been growing in my mind for years and about four years ago, the car we now offer began to take definite shape. The first step was to get the best engineering force in the country. Fred M. Zeder, Owen R. Skelton, and Carl Breer were the group I wanted. They began with a clean slate, and designed from the ground up. There were none of the usual engineering handicaps—no existing machinery, tools, jigs and dies to be considered; no pre-determined plant capacity or manufacturing lay-out to fit to; no executive fads or whims to be satisfied. We have made no compromises. These engineers of ours have solved scientifically every vexing problem of the past. I placed just one condition on their work—that was, that they used the very best materials adaptable to the work to be done and the strain to be borne by every part.

To make our car truly ideal, I tell you emphatically that anything less than the finest would take years off the life of this car. You know that the best results—in looks, in performance, in economy, in durability—can't be obtained without the design, materials and workmanship.

You can judge as to whether he was laying it on a bit thick; but there’s no question but that the 1924 Chrysler was quite an advanced car for the price, remaining close to the mainstream while laying on features and engineering that were definite boons for the owners. This was the car that made the company’s name; Chrysler himself had made a great name for himself already, but only as a turnaround artist at railroad and auto companies. Zeder, Skelton, and Breer deserve credit for actually creating the car—and for pumping out innovation after innovation for the next quarter century, pushing automotive engineering to new heights.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky