In 1957, Chrysler’s board, likely hearing about Ford’s and Chevrolet’s upcoming compact cars, decided they needed one of their own—but that creating it couldn’t interfere with their regular cars.

With no room at Central Engineering, Chrysler rented out a building on Midland Avenue (now called Midland Street) by Oakland and Davison. It was around 10-15 minutes from the headquarters, giving the aura, later, of being a secret project (which the press release later claimed it was, surprising the people involved.) In any case, the Midland Avenue building was handy because it was big enough for the entire team to work together.

The name Valiant came via Plymouth chief Loofborough’s secretary (who he eventually married), through the contest; she hadn’t been planning to enter, but then she saw Prince Valiant in the comics, made a connection with what a valiant person is, and submitted it.

Before then, it was program A901, while the drawings were QX1—Q-series, car X1. As the drawings were re-released for full production, they changed the designations—but in Australia, the 1960 Valiant was sold as the Model Q.

Few thought they could design the new car with the resources and time they had. This turned out to be an advantage. Al Bosley wrote, “top management didn’t believe they were going to do the car, so they just totally left us alone. We were able to get a few believers in Manufacturing and Purchasing... It wasn’t until the last two or three months of winding down the release process that it really became obvious that we were going to build a car, and the manufacturing guys really came and helped.”

The group followed a common pattern—the skunkworks. Put a relatively small crew into a tight space, with a clear mission, and sometimes the belief that others don’t think they can succeed, and miracles can happen. It worked at the original skunkworks, and, again, it worked at Data General, where an embedded reporter made a book out of it.

Without anyone second-guessing their decisions, and with a tight schedule, the team worked long hours, from early morning (6 to 7) to 6 pm—not after six, because then union rules mandated time-and-a-half. On Saturdays, they worked from eight to one. Some of the people in Body also had jobs at job shops after work; Al Bosley wrote, “every chance they got during their lunch hour, they would climb up on the drafting table and sleep. They brought pads.”

There were gags and practical jokes, and no air conditioning; in the summer, the windows had to be open and the flies came in, and one model maker attached harnesses to them so that a few flies would always be carrying red cellophane banners behind them. When one leader bragged about the gas mileage of his prototype Valiant, others added gallons to his fuel tank so he was getting 80 mpg, then started siphoning fuel away, stopping when he reached 5 mpg.

The spirit of the place was shown during one snowfall, when Chrysler facilities management and the owner both insisted the other one was supposed to plow; the union people stayed behind one Saturday to clean the lot, then started took up a collection to have it plowed. Bosley recalled, “The kind of spirit they had — they could’ve gone on strike, but they didn’t do that. They had enough concern and interest to take it on themselves to get that fixed. I always thought what real Chrysler spirit that was — and I always faulted Chrysler for not being able to deal with that kind of a problem.”

The Chrysler engineering process had the engineers make drawings of parts and assemblies, then send them to Materials Engineering, which specified the materials. This normally took anywhere from four days to two weeks. Al Bosley was concerned about the drawings getting lost, and suggested calling the department instead and noting the specifications on the blueprints without sending them in.

Materials Engineering flatly refused to go along with this idea, and Bosley said the Valiant team would simply recommend materials themselves; that was also rejected. Finally, the director of engineering brought Bosley and the Materials people into his office. Bosley expected to be fired; but the head of engineering told Materials to find a solution. That solution turned out to be sending a materials engineer to the Valiant team, which was an ideal solution—one which likely should have been part of every project.

Likewise, Body and Chassis Engineering were both in the same room. “When we had been in separate buildings, communication between us had been tenuous and difficult.” The Valiant came together far faster with the two department leaders working together daily to make room for the driveline, exhaust, fuel lines, and other undercar gear.

When a body designer drew a “buried” spare tire, they went to a chassis designer to ask if they could still fit a fuel tank. It took five minutes to agree (the body man agreed to move the spare tire as far back as possible)—a discussion which would have taken months going through channels. That brought up another issue, though—the fuel tank maker couldn’t form the shape; over time, they worked it out.

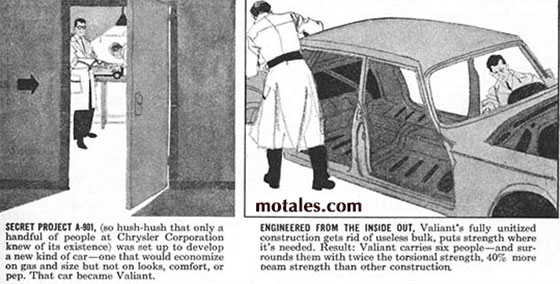

One good thing about the timing was that the terrible rust issues on the 1957 cars had convinced management to switch entirely to unibody designs, which could be pulled through rustproofing baths. That meant the Valiant was designed to be unibody from the beginning, without any stub frame or other workaround.

Chrysler’s first modern compact car, and the vehicle that would bring it a respectable global business, was created by a tightly knit team theoretically led by Bob Sinclair—who was put in charge by the board of directors. Dave Cohoe, Sinclair’s staff assistant, followed him around the world.

Al Bosley, in a later interview, called Bob Sinclair “a great blocking-back who moved obstacles out of the way and got things that we needed.” He didn’t have much technical input, though.

The board had laid out general goals and specifications in the third quarter of 1957. The car was done in 18 months, counting from when the team started working on it.

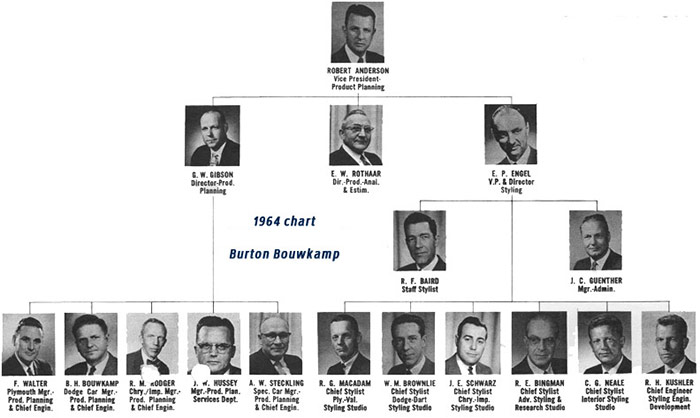

Normally, the mechanical design group would do basic designs and layouts. In this case, the original layout, prototype, and quarter-size work was assigned to Development and Design, a department led by Otto Winkleman. There are some key names who were quite influential in this group:

Winkleman led three engineer-managers: Bill Swan, Bob Bachelor, and Tom Wall. Wall was credited with the Valiant design; Bachelor was known as the father of Chrysler’s torsion bars, and worked on the Valiant with Wall.

Once the basic layout and design was organized, the project was staffed. Dave Toot of Chassis was given authority to choose his staff, given the importance of the new car; he chose John Betti to be assistant chief engineer of chassis, possibly because he was “especially aggressive,” and Ross Cooper to be assistant chief engineer of body engineering; Cooper ran a drafting center of around 150 people, in those days when it was done by hand. Betti went on to become assistant chief engineer for electrical and electronics, then went to Ford.

John Betti, the assistant chief engineer for the program, chose Al Bosley, who chose Bill Shellman, Sherwin Post, Gerry Schwander, and, a few months later, Don McDonald, as an engineering graduate.

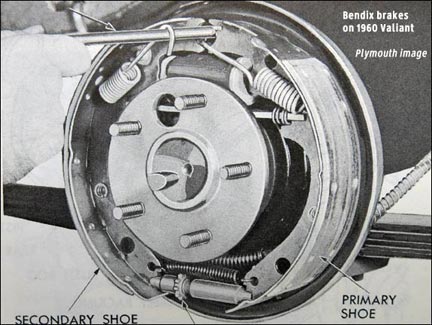

Al Bosley asked for somebody hired from another company who had engine or automotive design experience, to provide a view on how others did it. That person was Jim Rose, from Cadillac; and he did indeed bring over new-to-Chrysler techniques. These included the Bendix brakes, different parking brake setups, and a push-on/step-on parking brake. Jim also pushed for a lab like the one at Cadillac, which had a mock-up of the braking system mounted on plywood to test the systems, including different cable routes.

Chrysler used center-plane brakes then; the team didn’t know how to get center-plane brakes tuned or downsized to be the right size in time for production, and the company wasn’t sure it was worth retooling. The brake group claimed they were unstable and bad in water, but time has proven that view to be wrong.

One of the Engineering groups took product plans and converted them to job orders for the various groups; they'd send out orders for a new engine, axle, bumper, and so forth.

Other key people included:

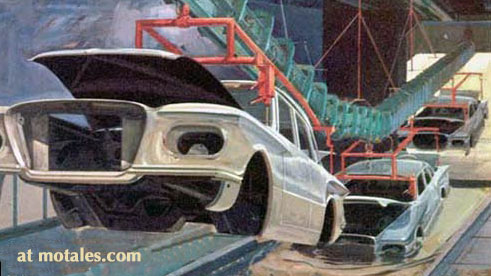

Chassis handled the suspension, exhaust, sheet metal, fender shields, steering, brakes, and such, because those were all part of the chassis on body-on-frame cars, and the company was only then moving to unibody designs. The Valiant was the first full unibody car Chrysler had done—if you eliminate stub frames, which were just used for assembly (because the full car couldn’t make the turns at the plant). The other unibodies in 1960 all had stub frames, as the Airflow had. Welded-on rails ran the length of the car.

Finally, people had to keep the records sorted out; the release system was very complicated, with each drawing marked out with the part’s use, dates, and so on. The person who did this for the Valiant ended up on the task team which re-created engineering and information systems later in the 1960s.

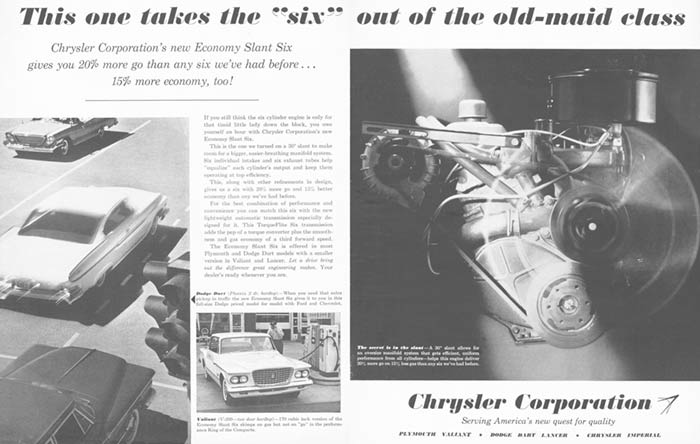

The first draft of the car used a 150 cubic inch (2.5 liter) four-cylinder engine, according to Willem Weertman and Al Bosley—before company leaders heard more about what GM and Ford were planning, and went to a 170 cubic inch six-cylinder. One of the executives realized a bigger version would be handy for their midsized cars and their trucks, and asked for a 225 cubic inch version to be made at the same time; both ended up in the Valiant.

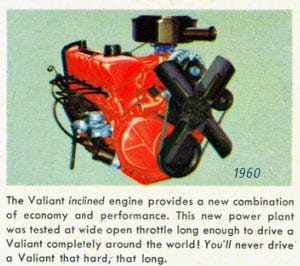

Most American engines then put the water pump on the front of the engine, run by a belt or from the crankshaft. On the Valiant, they ran the alternator and power steering pump and air conditioning and from the belt; space was tight, though. One team member thought of tilting the engine and putting the water pump next to it, instead of on the end, to save space. This avoided using other engine-shortening methods.

Al Bosley was never sure they leaned the engine the right way; the lean went to the passenger side to put the water pump more in the center of the car. Ed Guyer thought it should lean the other way to provide more space to the suspension and provide better access to the starter. They may also have been able to mount the alternator without a big dent in the fender shield. The entire underhood area was tight; leaning the engine the other way could have helped.

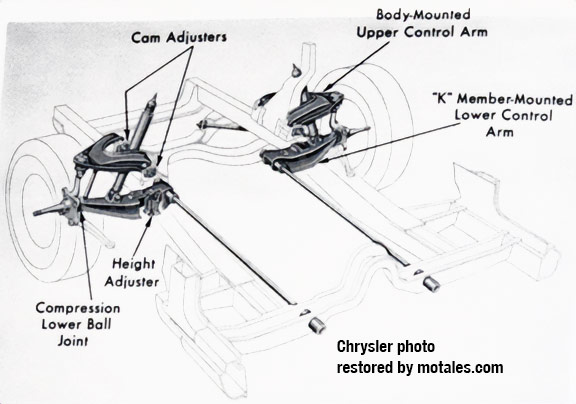

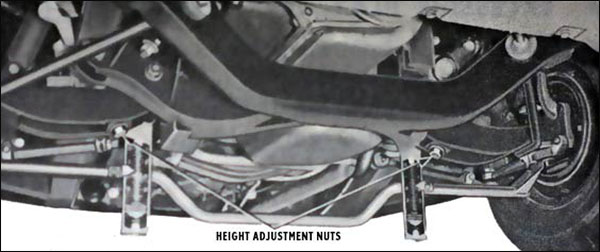

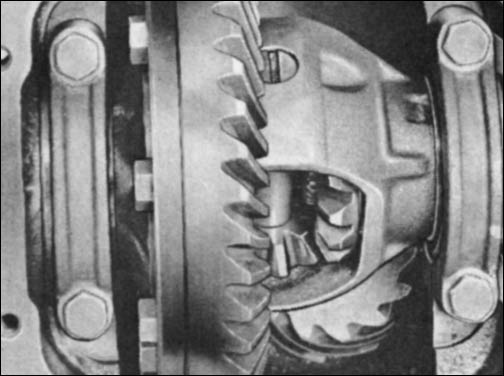

The engineering group tried to use what became failure mode and effect analysis in their work, talking about how things might fail and the results if they did. As a result, they changed Chrysler’s usual torsion bar front suspension design. Normally, these were adjusted using a tension bolt in the cross-member that supported the rear engine mount; the bolt could fail or become hard to adjust over time. The Valiant people changed the setup, making it easier to service and safer if there was a problem.

The early torsion-bar cars used tension lower ball joint, pulled down by the lower control arm. It it wasn’t properly greased or maintained, it could wear out the ball joint housing and pull out the ball, causing major problems. Ed Collier set it up for compression instead; its failure mode was being buried deeper and deeper into the ball joint housing itself.

Ed Collier also created a cam adjustment for caster and camber, replacing the existing shims. (An alternative method was Ford’s use of a bar.) It cost a little more but was far easier to adjust on the line, and in service—unless it rusts early. Certainly the line workers appreciated the easier method.

One minor but key innovation was using aluminum hubcaps instead of wheel covers or steel hubcaps; there weren’t many places to save oney, and this was one of them. While aluminum hubcaps tended to pop off, they avoided polishing or chrome plating; thy could just be bright-anodized. But when the car was nearly done, Styling and Marketing demanded wheel covers. This was a problem, because it takes a long time to get wheel covers tooled up. Al Bosley responded by calling the styling chief for the Valiant, Dick MacAdam, and suggesting trim rings as an alternative. Bosley thought they could roll the trim rings instead of making stamping dies, which cost more. MacAdam and the Marketing people liked the trim rings—they could be installed to taste by dealers.

When the car was nearing completion, another issue came up: where to build it, in the hundreds of thousands per year. Management chose Dodge Main, the huge multiple-floor factory dating back to around 1910. Two brothers ran the plant then, and they “were aghast” about making anything but a Dodge there.

The man in charge of keeping the car’s weight within budget, Pete Dawson, was married to an artist who helped with his “hate weight” campaign by making new posters every week. One solution not unique to the Valiant was punching holes into stampled metal, creating “lightening holes.”

One day, a stamping plant staffer asked them to change the hole sizes, because some of the workers were stamping out holes in the shape of coins for the vending machines. The stamping plant had been trying for years to make the holes elliptical so they wouldn’t work as slugs.

For NASCAR’s only compact-car races, in which Valiants trounced Fords and Chevrolets—winning first through seventh—the engines were individually tuned, built carefully with shot-peened connecting rods and such. It was a team effort, but the complete win led NASCAR to drop the planned series.

Al Bosley recalled that the main complaint about the Valiant, other than build quality, was the gasoline filler tube, which went through the trunk. It was placed there to save trunk space, but he felt they could have spent more time and effort to make it less intrusive. In addition, they wanted to hide the pipe with a metal cover, which in the long run would have saved money—because Chrysler had to go to court more than once about the pipe not being covered. It was far safer than a center-rear pipe, placed as GM had it under the license plate.

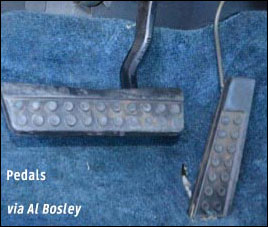

The throttle was controlled with a rod and ball joint; had they leaned the engine the other way, they could have done it with cables. A related issue was the floor-mounted gas pedal, because carpet or other things could be jammed into it. Eventually the Valiant did a hanging pedal, which the original team had fought a losing battle for.

The floor shift was not in the best place; one technician sold little extensions for the gearshift lever to make it easier for people to reach it.

Mainly, Bosley wanted just one more inch of wheelbase in it. When the program was well under way, and it was impractical to make any major changes, company officials told him they needed an extra inch of wheelbase. Their thought was using a longer front hanger on the rear springs and moving the rear axle back. That wouldn’t work because they already had barely enough space for the fuel tank. They suggested moving the front suspension forward, but the parts had already been released for tooling.

Bosley’s team checked the nominal wheelbase at various height positions, and found that with caster and camber, if the car was raised so the wheels were fully lowered but the rear axle was in the normal position, you could put a ruler in there and get a wheelbase of 106.5 inches. AMA specs had no requirement then about the car’s position. What was more, the way cars were built at the time left around a quarter to a half inch variance in the acutal length. The engineers advised the executives they could use 106.5 inches... but the real wheelbase was probably 106 inches.

Early production cars had sloppy assembly causing water leaks and misaligned body panels, which may have led to rust; but quite a few continue to survive.

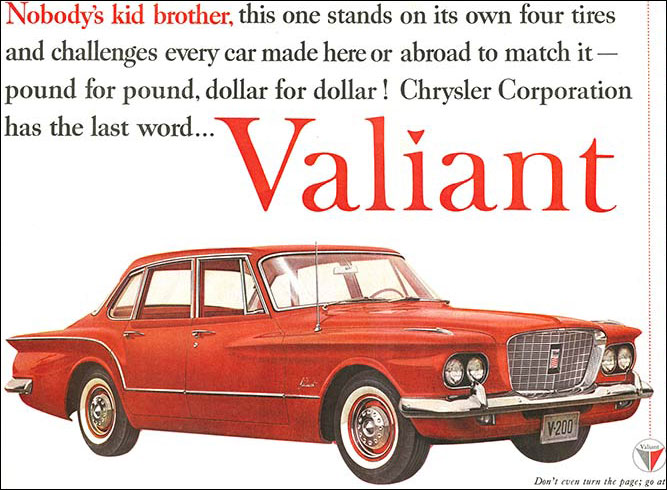

The 1960 Valiant series, created as a unique marque like Plymouth and Dodge, had two models—V-100 and V-200. Both were sold in four-door sedan and wagon form, with wagons having two or three rows of seats. Colors were silver gray, blue, green, white, and black, with the V-200 also available in red. The V-100 had a colorful nylon-faced, acetate-based seat upholstery in a block pattern; the V-200 used similar materials in a brocade-like pattern, with fine metallic threading. The V-200 also had color-keyed carpet rather than rubber mats, and interior trim coordinated with the outside paint; while both trunks had gray rubber floor mats, the V-200 had blue, green, or red interiors, while V-100 buyers had one color for upholstery and doors and the outside-color for other parts. They even had different steering wheels—blue-green with medallion horn, and two-tone with bright horn ring.

Ads of 1960 • Coming soon: the executives’ introductions, and the project leader’s rundown of Valiant engineering.