Henry Ford had every reason to be grateful for the world around him. He was never hungry, out of cash and homeless, despite having two attempts at making cars go bust. When he was ready with a third idea for a new car, the Dodge brothers, through their auto-and-bicycle parts business Dodge Brothers, not only loaned him the money he needed to get started and agreed to make the parts and assemblies he needed, but even went through his car to make it succeed where his past attempts had been dismal failures.

Dodge Brothers cars in a museum (photo: Tom Buss — see the story)

Ford, of all people, had good reason to be happy with people, but seemed quite bitter. Having to give the Dodge brothers a hefty share of his massive profits seems to have hurt, though they were responsible for his success; perhaps the fact that he had not done it on his own, rather than making him feel better about his helpers, stuck in his craw. Eventually, when the Dodge brothers separated, his bitterness was aimed at Jews, who he insisted in his newspaper were responsible for all the world’s ills. He only stopped when a reporter pointed out how many fatal crashes involved Model Ts, due to their abysmal brakes, and threatened to make that headline news unless he cut out his slander of an entire religion. It was a bit too late: Adolph Hitler had already been inspired (according to Hitler’s own writings).

Getting to the point, Henry Ford was an awful employer even by the standards of the pre-safety-rules days. Ford suspected his employees of stealing, not being sufficiently Christian, or, worst of all crimes, talking about joining a union. A worker injured on Ford’s line would be unceremoniously escorted out of the building. One who was overheard mentioning the U-word would be beaten to within an inch of his life. Never mind: by announcing the $5/day wage, then quite high, Ford brought a long line of new applicants to his door every day. (To actually get that wage, you had to already have been an employee, have the right size family, go to the correct church every Sunday, and submit to having your home searched on a regular basis for alcohol and other contraband. Very, very few people qualified for $5 per day.)

At Ford, people worked to the stopwatch. Workers did not get bathroom breaks, lunch breaks, or time to maintain tools. The assembly line was constantly sped up, and every time people adjusted it went faster.

The Dodge brothers, on the other hand, were known as very good employers, despite their multi-story factory. On hot days, they distributed beer to the workers; through the year, they had doctors and nurses on-site to deal with injuries and sickness. Simply tossing out an employee who had been injured was not in the Dodge Brothers menu.

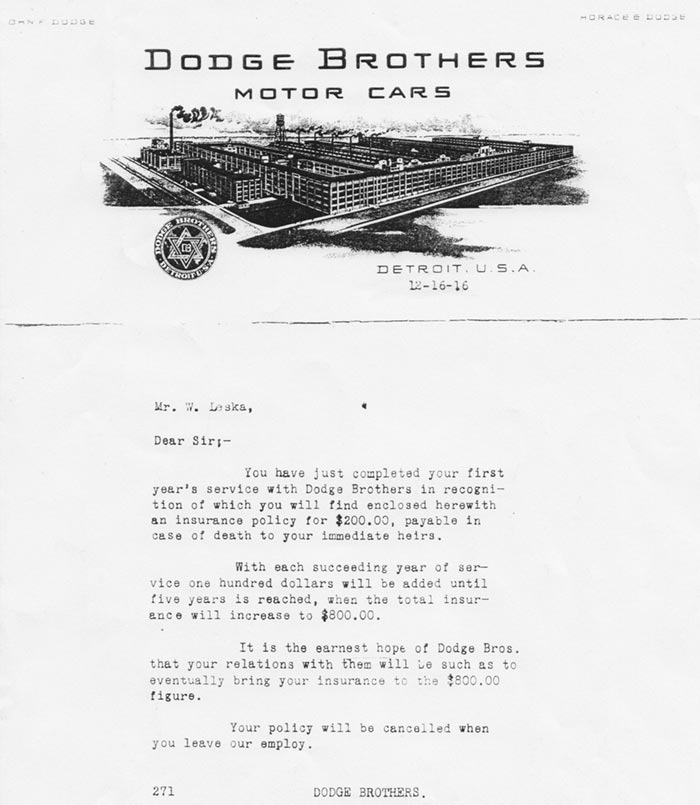

While, today, many employers provide free life insurance, it was not the industry staqndard when the Dodge Brothers did it, as shown in the 1916 letter above. The Dodge Brothers did not have a "Sociological Department" to spy on its workers, as Ford did. While not exactly pro-union, the Dodges did not seem to worry about it much. They had generally been good to their employees, and their employees were generally good to them.

Robert Lacey, in Ford: The Men and Machines (1986), wrote about one worker, Charles Madison, who left Dodge Brothers when the $5 Day was announced to great fanfare. After one week working for Ford, he came back; he’d have to work a grueling six months at Ford to qualify for profit sharing, and the work was far too exhausting to do anything, even reading, after work. He took the Dodges’ $3 a day, remembering, in Lacey’s words, Ford’s “hell on earth that turned human beings into driven robots.” Lacey quoted Madison further:

I resented the thought that Ford publicists had made the company seem beneficent and imaginative [with the $5/day wage] when in fact the firm exploited its employees more ruthlessly than any of the other automobile firms, dominating their lives in ways that deprived them of privacy and individuality.

Dodge Brothers did not grow quite as large as Ford; nor did it make quite as much money. It did make a far better car, moving to an all-steel body early on, and it aimed at selling a premium product for a mainstream price. The Dodge Brothers car was not by any means a Packard or Chalmers; but it was, like the much-later Plymouth, a fairly hefty step above a Ford, for a reasonable price premium. As sales boomed, one can’t help but think the Dodge brothers—known as much for their hard partying as for their hard work—enjoyed themselves much more than the dour, oddly bitter Henry Ford.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos