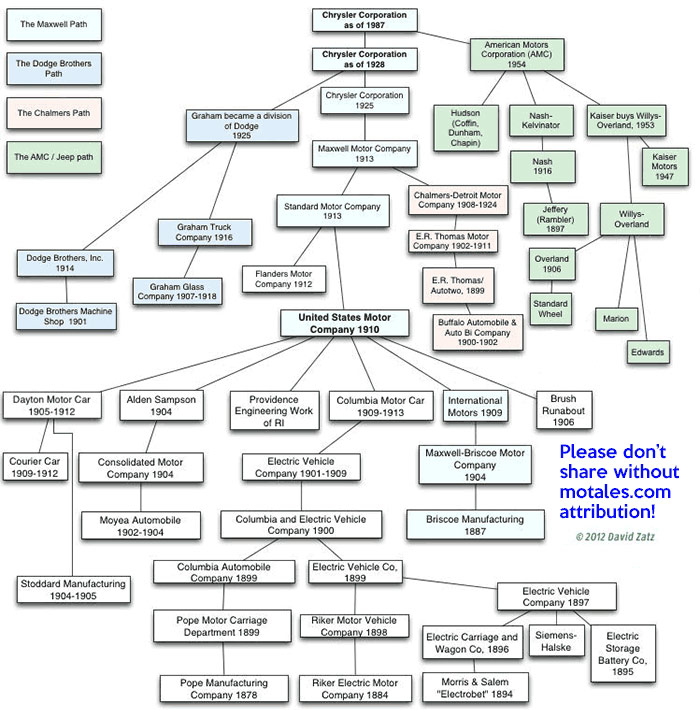

The 1924 Chrysler was a revolutionary car made by Maxwell Motors. Chrysler Corporation was created in 1925, but it was just a legal exercise—which may lead one to ask where Maxwell came from? We won’t go through the full family tree (pictured below), but we will touch on enough even events to give you an essential history of the Chrysler that lasted from 1925 to 1998.

Maxwell is not the oldest automaker on the chart—that was Riker Electric—but it was the main thread which turned into Chrysler. It began in 1904 as the Maxwell-Briscoe Motor Company; financier Benjamin Briscoe had hired away the experienced engineer Jonathan Dixon Maxwell from Ransom Olds, after the pair had developed the Curved Dash Olds, the first car made on an assembly line.

It did not take long for Maxwell to develop his own car—quite a good one, based on contemporary accounts—and they sold an impressive 542 of them in their first six months. One attraction was using a driveshaft, which worked better than the still-standard chain drive. In the car’s second year, 1905, it won a “perfect score” (no repairs needed) on the Glidden Tour from New York to Jacksonville; it also won the “climb to the clouds” contest up Mount Washington, in the class of cars under $2,000. Maxwell then won the Deming Trophy on the Glidden Tour in 1906, also setting an unrelated 3,000-mile nonstop speed record; and in 1907, a Maxwell traveled from New York to Boston without problems despite running on alcohol rather than gasoline.

It’s still not certain who decided that the country should just have one major automaker; but new automakers seemed to arrive every week, and Durant and Briscoe agreed that putting every existing major automaker into one single company would create more stability. They gathered every executive together for talks. Henry Ford refused to take stock in the new company, wanting cash, and as they negotiated the terms, the plan leaked and the bankers (under J.P. Morgan) fled. That ended the talks.

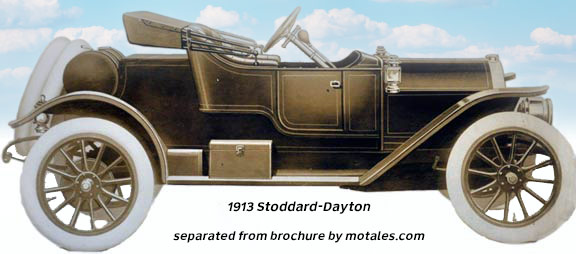

Durant and Briscoe did not merge their companies together, as one would expect; that would have been the easy path. Durant started creating General Motors, and Briscoe started working United States Motor Company. He brought companies together with little respect for whether they were solvent. Brush Motor Car, sponsored by Ben’s brother Frank Briscoe, had a hit car, but it was never updated much, and sales dried up. The other companies brought in during 1909-1910 were Dayton, Courier, Columbia, Stoddard, and Alden Sampson; Brush was the best of this bunch, though Columbia Motor Car collected royalties on the infamous Selden patent on the motor car. Columbia’s obsolete products could not stand on their own. With this collection of largely obsolete or unpopular or niche vehicles in hand, Briscoe converted its huge New Castle plant to making parts in 1911, moving Maxwell production to its new acquisitions since they had spare capacity. In that year, too, Ford won a lawsuit invalidating the Selden patent.

Good news for 1911 was having four Maxwells in the Glidden Tour (one independently entered) run from New York to Jacksonville without any problems (along with an independently entered Maxwell), dominating the $1,201 to $1,600 touring car class. Walter Flanders banked a win for Studebaker in the up-to-$800 class; both Flanders and Studebaker would play a role in Maxwell’s future.

U.S. Motor was overextended and untenable; the next market downturn threatened it with bankruptcy, and Ben Briscoe rapidly dropped all the unprofitable brands—everything but Brush and Maxwell. U.S. Motor went into receivership in 1912, paving the way for the company’s first corporate savior—and its first savior named Walter.

Walter Flanders, who some credit with Ford’s assembly line, had been one of the creators of EMF (the F was for Flanders); after Studebaker bought the company in 1910, he started the Flanders Motor Company. Then he created the Standard Motor Company, a shell, to buy the U.S. Motor Company’s assets out of bankruptcy along with his own car company; Standard was essentially just the old Stoddard factory in Dayton (which had largtely been switched to making Maxwells), the parts plant in New Castle, and the Flanders car and factory.

When the deal was done, Flanders decided to rename his new car to “Maxwell Six” for name recognition, and renamed Standard Motor Company to Maxwell Motor Company for the same reason. Profits followed quickly, and in 1917, Maxwell started making cars in the huge Chalmers plant in Highland Park, Michigan, trading the space in return for selling upscale Chalmers cars at his own dealerships. Despite the new sales outlets, Maxwell ended up owning 90% of the unprofitable Chalmers.

The 1920 recession and Flanders’ earlier departure nearly killed Maxwell; it owed $32 million to creditors at its lowest point, and 26,000 out of 34,000 1920 cars were unsold. (This was, incidentally, the same year Maxwell engineers started using a driveshaft emergency brake, beginning a Chrysler tradition.) Walter Flanders was in ill health which stopped him from taking over; he died in 1923.

In 1921, Maxwell stopped production as engineers patched weak axles and gas tank mounts. A committee sought out the famed Walter Chrysler, who had turned around Willys-Overland and several General Motors companies. He held out for $100,000 per year, plus stock options, which was a record payment—and he got it from a desperate Maxwell, just a little too late. The company was forced into receivership and its creditors had to buy it back for $11 million (bidding against Billy Durant, among otyhers) before Chrysler could fix it. Another new Maxwell Motor Corporation came out of the ashes, with Walter Chrysler elected chair of the board. He immediately bought Chalmers Motor Company for $2 million, presumably to keep its factory.

Chrysler had met three brilliant engineers at Willys-Overland: Fred M. Zeder, Owen R. Skelton, and Carl Breer (shown above as Breer, Zeder, Skelton), dubbed the “Three Musketeers” by friends. They had met at Studebaker—the company which had bought EMF—and moved on to Willys; Chrysler set them up as a consulting firm when he lost control of Willys (to John North Willys) and lost a bidding war for the plant where they had been working (to Billy Durant, who made the Durant there).

The three engineers had two major tasks: fixing the Maxwell and creating another new Chrysler car, the first having been sold to Billy Durant some years ago. The engineers researched the problems of the Maxwell cars to fix root causes rather than doing patch jobs, resulting in the “Good Maxwell”—a vastly improved Maxwell 25. Teams retrofitted already-built cars to match the changes being made on production lines.

At that point, the industry considered blueprints to just be the start; problems, according to Carl Breer, would be found by workers and fixed by supervisors or engineers, but without changes to the original blueprints. The Zeder-Skelton-Breer (ZSB) team laid down the law to Maxwell’s people—changes had to be run by engineers, agreed upon, and put into blueprints (or the original blueprints had to be changed), with records kept.

Their main work was creating the Chrysler Model B (why Model B? Presumably because Durant had the Model A). They did apply their innovations to the 1924 Chalmers as well, including revolutionary new four-wheel hydraulic brakes, which actually made it to the Chalmers before the Chrysler. They were not the first four wheel hydraulic brakes, but they were the most effective and the first on a mainstream car; and Chrysler’s engineers signed the patents for their workable system back to Lockheed, who had brought them an unworkable one. The car was made in two plants, one in Windsor, Canada and one on Jefferson Avenue in Detroit; both made Maxwells as well as Chryslers.

| Car | 1924 | 1925 |

|---|---|---|

| Maxwell | 48,124 | 27,153 |

| Chrysler | 31,020 | 105,190 |

| Plant | Maxwell | Chrysler |

| Detroit | 1,920 | 429 |

| Windsor | 3,593 | 1,613 |

The new Chrysler car was introduced to the public in 1924, during the New York Auto Show. Production of the Chalmers quickly ended. From 79,144 cars in 1924, the new Maxwell-Chrysler combine produced 132,343 cars in 1925. Then Walter Chrysler and Harry Bronner used their massive stock holdings to form a new holding company (Chrylser Corporation) and take over Maxwell. The last Maxwell car left the factory in May 1925, updated somewhat and renamed to Chrysler Four. The company never looked back.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos