GM created its new Saturn brand in early 1985.

When a reporter asked Lee Iacocca if Chrysler had anything similar in the works, Iacocca said they had a program called Liberty; he may have pulled that name from his work to restore the Statue of Liberty. Then, in March 1985, Lee claimed Liberty had already existed when Saturn was announced; and that it, too, was working on a small car, to be launched in 1990. This was apparently news to other people at Chrysler, or perhaps he had already been laying the groundwork for the group.

In any case, the Liberty Group was established in mid-1985, renting part of the Parker Chemical Building on Stephenson Highway and Whitcomb (months later, it moved to Featherstone Road in Auburn Hills). There were later Liberty Groups and multiple projects under the first one, so the story does get confusing. Any errors are mine, not Michael’s.

Under general manager Dick Johnson, Liberty originally had three major programs:

The Truth About Cars’ Corey Lewis tracked Lee Iacocca’s various statements in March and April 1985. In March, Iacocca talked about the composite-based car, showing a working prototype; in April, the story apparently changed, with the small car assigned to Diamond Star Motors (Mitsubishi/Chrysler joint venture), which in reality did not make an inexpensive small car, but a trio of sporty ones. It was in April that Lee claimed Liberty was in the works before Saturn, which, again, may have been true, from a planning perspective.

A year later, Corey wrote, Lee claimed that Liberty had saved up to $2,000 per car; and Liberty was to create new small cars at Belvedere, replacing the Omni and Horizon. This last part was, as noted earlier, true enough; it was the group headed by Jim Lylijnen, a highly regarded manager. Tom Gaynier created coffee cups with “Liberty II” graphics. According to Michael Dougherty, who started at Liberty in May 1985, the Liberty II program used a first-generation Ford Taurus as a mule to disguise their work.

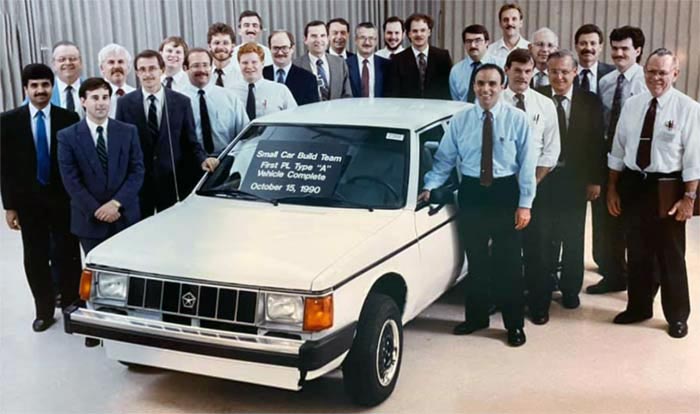

In 1989, Francois Castaing, the new Vice President of Engineering, halted work on the K-car replacement. He wanted to adapt the Eagle Premier architecture to the small car, dropping the more conventional design they had been working on. He also decided that rather than forwarding the project to Advanced Vehicle Engineering as usual, they would continue to develop the car internally. At that point, the group had around a hundred people under Glenn Gardner.

This group, run from Highland Park, was the first large-scale platform team to design a car, according to one account; most accounts say the Viper came first, and certainly the timeline supports that it was Viper, then large car (LH), then Dodge Ram 1500, and finally small-car. (The creation of the Chrysler Technology Center was the first actual cross-platform team within Chrysler since 1960.) In any case, the platform (cross-functional) teams drew people from different disciplines together to create groups of cars.

In 1989, Bob Lutz spurred the creation of a new Liberty Group (later renamed Liberty Technical Affairs) to emulate the famed Lockheed “skunkworks.” The idea was to have a group of free-thinking people who would adapt emerging technologies and systems.

Lutz was impressed by the accomplishments of the original Lockheed skunkworks (named after the smell of their building), and wanted to use their methods. His new Liberty Group, run by Tom Moore, was charged with creating concepts for vehicles that were still at least 15 years away. Their cars, shown at the Detroit Auto Show, got heavy publicity; and they did preliminary work on the electric minivans, as well as the “through-the-road” hybrid system that never saw the light of day.

Liberty and Technical Affairs was first at Stephenson Highway and 13 Mile Road; around 2000, it moved to Rochester Hills.

One example of a Liberty release was the 2002 “MAGIC engine,” which had a series of small changes to the Chrysler 4.7 liter engine. Thomas Moore, head of Liberty and Technical Affairs, claimed that small changes, totaling under $200 per engine in added cost, could make a tremendous impact—in this case increasing fuel efficiency by 14%. The changes included a 4% higher compression ratio, made possible by an intake port air-gap thermal barrier; on-demand piston oil squirting; charge motion control using swirl-control valves; friction reduction via crank offset, lower oil ring tension, and a shortened coolant jacket; more precise cooling; and cutting parasitic losses with a revised oil pump.

Some aspects of the MAGIC engine were used in the Chrysler 3.7 liter V6, according to Tom Moore, including the as-needed squirters and thermal management.

The group had a Durango demonstration vehicle using their Apollo project, which would add $500 per vehicle but increase efficiency by 25%; this used a stop/start system, better cooling, an electric water pump, belly pans, grille shutters, and electro-hydraulic power steering as well as the MAGIC engine. These technologies did come to be used in the Fiat years.

Damon Blumenstein pointed to the JSX project; built on the JS Sebring platform, it had a cast magnesium unibody structure with carbon-fiber body panels and a hybrid low/high voltage electrical system. Power came via dual V-twin coupled engines (see below). He also worked on a version of the Apollo Durango which used twin I-4 engines, paralleled with a dual clutch transmission. He referred to both of these as “sort of the original MDS system on steroids.”

At least two of the V-twins ended up at the Roush Collection; dubbed the Gemini engine, it did not have a common block for the two engines. Roush was a contractor for Chrysler; and as Liberty only had around fifty employees, some aspects of engine development were outsourced. The idea behind using the V-twins was having a modular V-4 engine, coupled by a clutch, which would provide cylinder deactivation without pumping losses by simply disconnecting the second engine when it wasn't needed. They shared coolant and lubrication systems. According to Ronnie Schreiber in The Truth About Cars, who uncovered the information in this paragraph, the engine met its test criteria.

Rumors swirled around the automated manual transmission, which used two clutches to shift as smoothly as a conventional automatic, but with more efficiency due to the lack of a torque converter; patents were issued; but it never came to fruition.

In addition to these, Damon worked on the EPIC minivan fuel-cell program, which would have outfitted the electric minivans with hydrogen fuel cells.

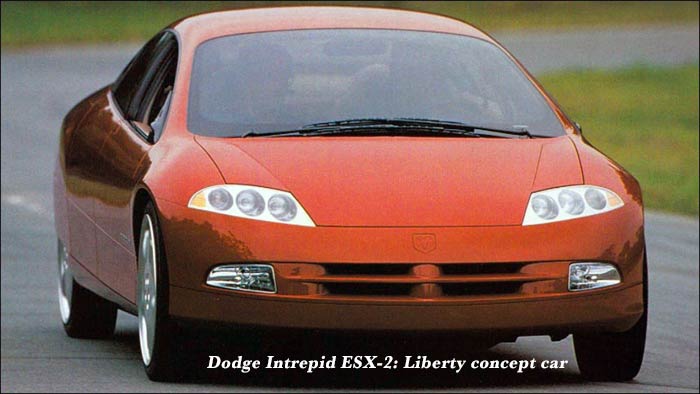

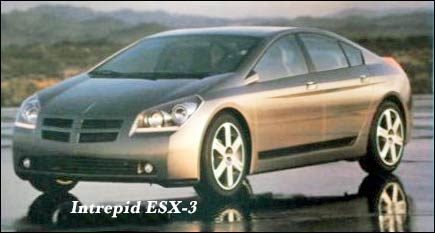

Not all views of Liberty Group and Technical Affairs were positive. Former employee Evan Boberg wrote that some of their presentations were simply made up, complete with concepts’ specifications (particularly in the case of the various Dodge Intrepid ESX hybrid-electric cars, released in 1997 and 1998). His book Common Sense Not Required was harshly critical of the group, as well as both AMC and Chrysler Engineering. There were likely both good and bad people, and good and bad projects, at Liberty Technical Affairs.

Later, Ian Sharp wrote that Liberty “was a good idea, but it was done in a corporate manner, and that limited what it could do ... there also has to be an independent auditing and financial arm, understanding how experimental R&D groups work. We got maybe 20% of the way there with Liberty, but budgeting and purchasing were always under the corporate financial group.” Corporate constraints on Liberty, he wrote at Allpar, spelled a death knell for his advanced hybrid-electric Patriot F1 car.

While there may well have been failures, there were also programs that either bore fruit or came very close. Bob Feldmaier pointed out that the power liftgate idea came from Liberty; Bob got it ready for production. Ron Killen wrote that they “had several good programs that never made it. The all aluminum Neon was ahead of its time. The three-cylinder program had potential as well.”

The two-stroke engine program came close to production. Teelo Berry wrote that this, officially dubbed Alternative Engine Task Force, resulted in working prototypes in Sundance/Shadows and aluminum-body Neons. Teelo, who was part of that team (and then the direct injection team in the 1990s), wrote that it was sponsored by Francois Castaing and Bob Lutz, set up as a joint venture with Mercury Marine, and led by Joe Goulart. The 20-person team worked from 1989 through 1995; Phase 2 engines were 1.2 liters in displacement and tested for 100,000 miles. The Phase 3 engines were 1.5 liters, using a balance shaft, external EGR, and dual plugs per cylinder, with a direct injection system running 1,000 psi. It produced 95 horsepower and 128 pound-feet of torque, more power than export Neons had, with 10% greater gas mileage.

Automotive Industries took a test drive of a car with the two-stroke engine, and praised its smoothness and performance. It was meant to appear in the Neon, but oxides of nitrogen, a controlled pollutant, were too high, because the engine burned so lean; and the EPA wanted on-board diagnostics which were not relevant to the engine. Each problem could have been overcome, but gas mileage was not a priority for most customers, and the company let it drop. A press release pointed out that “Chrysler engineers have gained valuable experience in technologies associated with injecting fuel directly into the combustion chamber, according to Floyd Allen, executive engineer, core powertrain.”

According to Teelo, Liberty was the origin of active grille shutters, belly pans, and other aerodynamics technologies at Chrysler; but Castaing said that the real product of these R&D programs was good engineers.

The group was shut down after Tom Moore retired; by then, Daimler had taken over. Daimler had a similar, much larger department; and Liberty’s work on hybrids was a liability, as Daimler was betting that hydrogen fuel cells were the future. In any case, Liberty Technical Affairs was shut down under Daimler, and did not return.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky