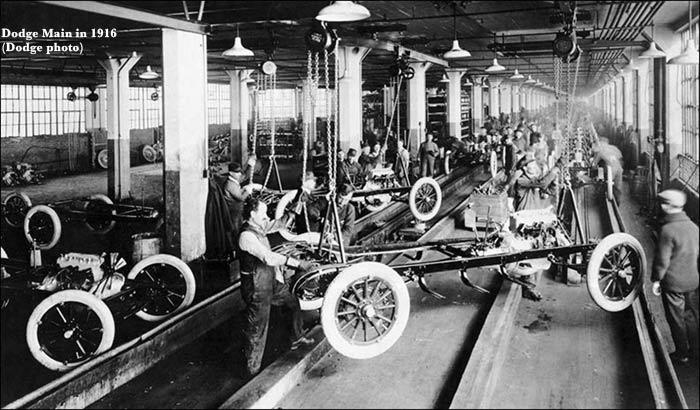

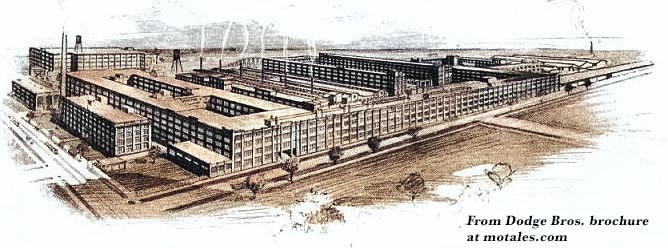

After the turn of the century, John and Horace Dodge needed more space to make components and engines for Ford and other car makers. The brothers decided on Hamtramck, which had been incorporated in 1901, for their factory; it had a rail line to Henry Ford’s assembly plant and room to grow. They bought 176 acres of land and started working.

Hamtramck, surrounded by Detroit on all sides today, was a fairly rural community mostly populated by Germans. As the Dodges’ plant grew, the population density exploded and the demographics tilted towards Poles; later, African-Americans, also attracted by the Dodge complex, moved in, and by the 1980s, it was a well-integrated community.

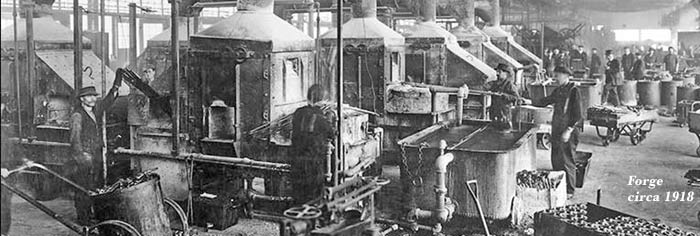

Albert Kahn designed the primary building on East Grand Boulevard, between Joseph Campau Street and Conant Avenue, and construction began in 1910. Other building included a forge to make crankshafts, suspension parts, and such, and a foundry to cast parts camshafts and other parts. Plant 4, separated by a railroad from the rest of the complex, was in Detroit itself; they were connected by an underground tunnel to let trucks get to the receiving dock via Conant Avenue.

The complex had a small hospital, private telephone system, and its own fire department.

The first Dodge Brothers car was sold in 1914. Some time later, Ford dropped its dividend, and the Dodges sold their interest in Ford, gaining a phenomenal $25 million—quite a large amount at the time—though it took a trip to the courts to make Henry Ford live up to his contract.

Workers had a better deal than those in Dearborn; the Dodges were good employers overall, and they tried to make working at Dodge Brothers far more attractive than any other local automaker. They tended to care more about worker safety than Ford, as well, with lower injury rates. As a result, workers at Dodge Brothers tended to stay through their full careers; it helped that the brothers provided free sandwiches and beer in the plant. In the 1950s, observers noted that there were many long-time employees, and a general spirit of teamwork and cooperation.

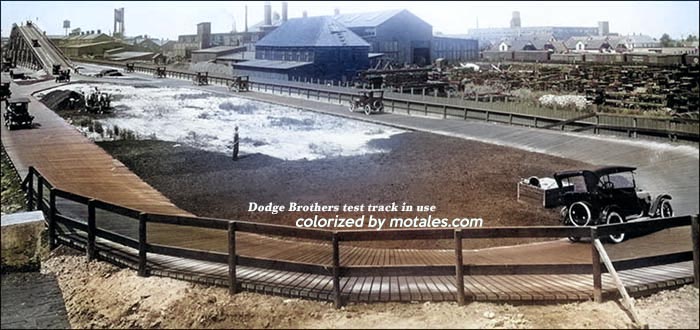

The plant was fed by truck entrances on Joseph Campau Avenue and on Conant; the finished cars left via Joseph Campau. Numerous rail sidings brought raw materials and parts in, and took cars out. Individuals could still buy a Dodge Brothers (or, later, Dodge) car and pick it up at the plant. The company also tested its cars on an internal test track; and built many of its own parts, with forging, casting, and machine shops on-site.

Within the offices were white marble fireplaces, with large brass spittoons; both were still in place in the 1950s, though the fireplaces were never used.

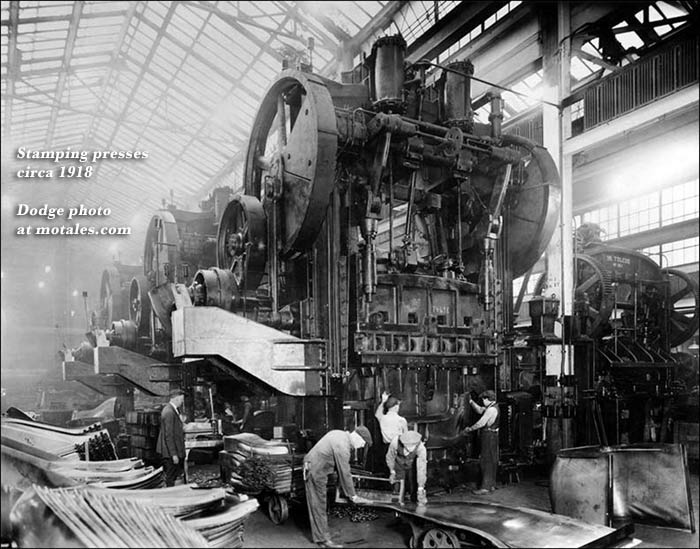

Kahn’s buildings used reinforced concrete structures, usually with concrete columns every 24 feet and 13-foot-high concrete ceilings including steel channel inserts to suspend heavy machinery. The site grew to have 35 ancillary buildings from 1910 through the 1960s, growing gradually, including a five-story maintenance structure with shops for skilled trades. They were often connected by extensions or bridges, and a person could walk across the complex without having to go outside. The assembly line eventually crossed buildings as well. Information would be sent to the various departments via teletypes.

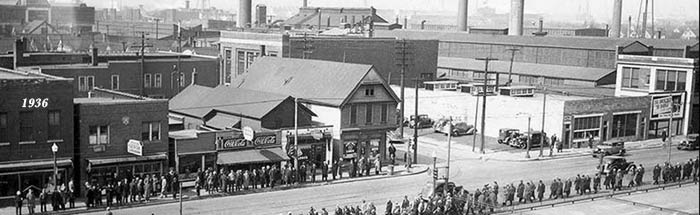

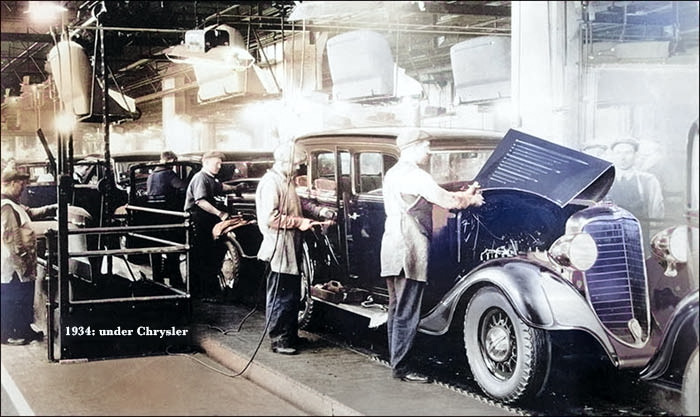

The Dodge brothers died in 1920, and Chrysler bought the Dodge Brothers company in 1928, keeping Dodge cars centered there. The UAW established itself at the plant through a two-week sit-down strike, during which locals brought food and drink to the strikers; in the end Chrysler gave in. The strike had no violence or deaths, which was fairly unusual for the time. The difficulty of auto work in those days should not be understated; those responsible for sanding the body had no protection against dust getting into their lungs, and those in final assembly included some underbody workers, in a pit under the cars. Their bodies took a beating, and at times fluids from the car splashed into their faces. The noise was ever-present, and the assembly line rarely stopped. The job wore people out, and injuries in any auto plant were common.

By World War II, around 45,000 people worked at the Dodge complex, which kept growing long after the Dodge brothers had passed on. In the 1950s, they added a much-photographed pedestrian overpass so workers could cross Joseph Compau Avenue to the parking lots safely. By then, numerous shops and bars and sprung up around the plant; but plant workers still wore the Dodge Brothers six-pointed star on their badges.

Over time, the line was reworked over and over until it became a bit absurd. The late engine designer Pete Hagenbuch told me that he had tried to follow the assembly line across all six floors. It could start on the second floor, go up to the fourth, come down to the first, and so on. “It was like they put in different parts of the line as things came up. ... a couple of guys in the Institute went down one day and tried to spend the whole day following the line, and they got so tired that they quit at lunchtime, and they hadn’t gotten [to the end] yet.”

In the 1950s, most stampings came from the Pressed Steel Building and the Body Building, with more coming by truck and rail. Within the Body Building, stamping was done on the first floor while body assembly started on the eighth floor. The six-story Assembly Building #2, a thousand feet long and just 100 feet wide, did most of the body trim, including sewing up seats and making convertible tops.

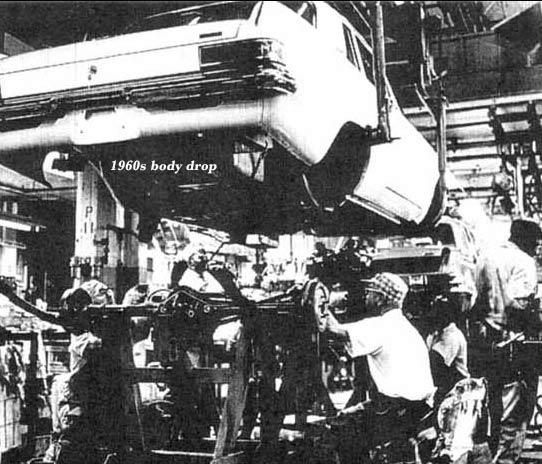

Bodies were carried on unpowered trucks, held up by four casters, two guided by an open-channel track and two moving freely. The line could move at up to sixteen feet per minute, so they could produce sixty bodies per hour on each line—but generally they were not run at their top speed.

Trimmed bodies went from the third floor of Assembly Building #2 to the final assembly lines; there, workers took the bodies off the trucks, turned them by 90°, and pushed them onto the final assembly line, which crossed a bridge to go into Assembly Building One. Then they got their front ends, fenders, hoods, and such, and the body was dropped onto the chassis and fastened down. The chassis were assembled in the main building, put together upside down to make it easier to attach the suspension, brakes, fuel lines, and exhausts. They were flipped just before the body drop. Finally, the car was started and driven from the line.

The Dodge foundry was self-contained; it cast engine blocks, clutch housings, manual transmission cases, and so on. Chips and turnings were put back into the raw materials. Another department heat treated various parts, and other plated fasteners and such. Induction hardeners treated V8 rocker arms; valve inserts were chilled with liquid nitrogen before being put into V8 heads.

Dodge had its own generating station and provided steam for industrial operations and heat; the generators provided 110-volt single-phase power and 220V and 440V three phase, as well as 180V and 360V AC for hand tools. The plant also provided DC power for hoists, elevators, and conveyor drives; the DC power was created by new engines being run in during hot testing. The AC was created from eight coal-fired boilers.

Finally, the plants had an executive dining room, a cafeteria for office and plant employees, and a facility in Plant 4 which made hot food for distribution to the factory areas. The medical facility was still staffed with doctors and nurses, as it had been under the Dodge brothers.

One former worker (whose name is not available at this time) wrote about his time at the plant for the W.P. Chrysler Club; he mentioned a small grocery across the street, along with various bars and restaurants; the Flying Duck bar was at the foot of the employee walkway. Customers were automatically set up with a shot and a half-glass of beer. The restaurants, he recalled, were good and cheap. He added that the workers were “hard working, proud, dedicated people [who] I came to respect.”

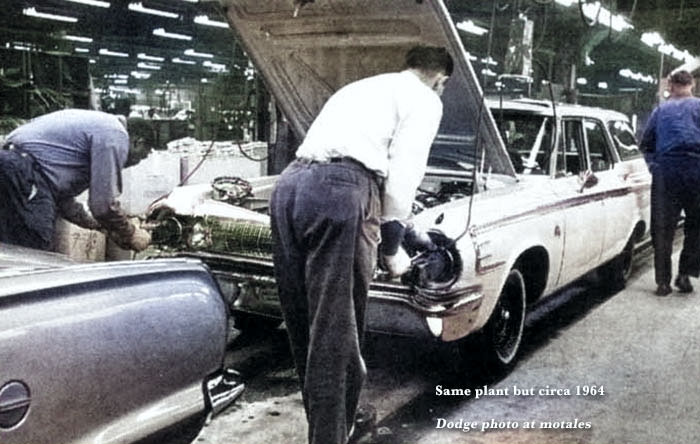

Through the 1960s, Plymouths were built at the plant as well—B-bodies from 1964 to 1966, Barracudas from 1964 to 1974 (the entire run), Volares from 1975 to the end, and (this is disputed) Valiants for most of their run. They made Dodges including the Lancer, Charger, Challenger, and Aspen, as well as all the “standard” Dodges. DeSotos ran through Dodge Main from 1956 to 1959, and Graham Brothers trucks were built in 1928 and 1929.

As time went on, problems grew worse. The complex was inefficient for modern machinery, and had been created for much smaller cars. Conveyor belts went outside because of the much longer size of cars and increases in production; at least one car fell off the conveyors while it traveled outside.

Oil crises hit Chrysler just after it had gambled on large cars, and in 1979, when the plant was only making Volares and Aspens, they announced its closure at the end of F-body production. Chrysler had little choice, but it was rough on the city; the plant was responsible for a quarter of its revenue.

Dodge Main was empty for a year; demolition would have been frightfully expensive for Chrysler, so it stayed up but empty. Then General Motors got heavy subsidies from Detroit and Hamtramck to build a new plant on the site, promising numerous jobs. In Detroit, around 1,500 houses, numerous businesses, two churches, and a hospital were cleared; in Hamtramck, just eight houses and Dodge Main came down. (GM later reneged on their promise of jobs, making the plant highly automated instead.)

Chrysler sold the plant for one dollar, which was likely a good deal compared to spending tens of millions to demolish it. True to Chrysler’s nature, they made no effort to save plant records, leaving them in place during the demolition. Likewise, no systematic effort was made to save any ornamentation; nor was a photographer sent through to get final photos.

Taking down Dodge Main was quite hard because the Dodge brothers made it much stronger than needed for just about any purpose. They played hard, but they worked even harder, and the Dodge Main plant was a testament to their brilliance and work.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky