The year was 1972. Fuel crises were still in the future, but Chrysler was working on putting turbine engines into production cars (they did end up in the Chrysler-engineered Abrams M1 tanks)—and Ward’s had just predicted 10 million Wankel-engined car sales in the United States by 1980.

Companies accounting for three quarters of vehicle sales in the U.S. and Japan, and half of production in Europe, had licenses to build Wankel engines. Should Chrysler follow?

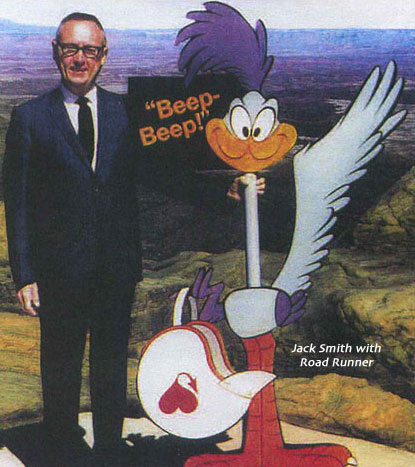

Chrysler’s Jack L. Smith, manager of chassis product planning, was asked to report on the question, reporting to J.W. James (the director of corporate product planning). His report, dated August 31, 1972, was highly skeptical and rather humorous at times.

Smith started out, after establishing the popularity of Wankel licenses, by saying:

Such colorful news has abounded in the Press during the past year, and has frequently included statements by “experts” who have touted the benefits of the Wankel and foretold the decline and fall of the piston. Those forecasts have been inspired almost exclusively by faith in General Motors and by expectations of total success from their dedicated efforts to make the Wankel work. ... The prospect of such a revolution has been affecting the stock market to a remarkable extent; “Wankel” has become a magic word and speculative responses to Wankel “news” have been dramatic.

Smith added that much of the positive press given to the Wankel had been generated by a small number of evangelists—he cited David Cole, Robert Brooks, and auto writer Jim Dunne, referring to their “prophetic opinions” and “gung-ho viewpoints” which (in words which bring Tesla to mind today) “displayed a sameness which brings to mind the word ‘clique’ (if not ‘cult’).”

Mazda Wankel engine (Softeis photo – see the license)

Smith does not seem to have joined the Wankel cult, but he went on to point out that those who did not own licenses to build the engines “are now finding themselves cast as stick-in-the-muds who are missing the boat.” The company had only until September 10 to decide, though he thought they should seek an open-ended extension while they conducted more research.

While skeptical, Smith did give the Wankel a chance. He noted that two cars were made with the engines, one from NSU (Audi)—the RO80, made in West Germany; and at least two from Mazda. The NSU RO80 was launched in 1967, and early cars had numerous problems and recalls; production was around 20-25 per day when the memo was written, with just 30,000 made. The retail price was around $6,000, double the price of a midsized Plymouth of the day. The engine had 25% less fuel economy than equivalent piston engines, and higher cost. However, NSU’s chief development engineer said that Mazda was much more advanced.

Mazda had “intense development activity since early 1961 license date.” Mazda had extremely well optimized “designs, materials, finishes, tolerances, and manufacturing skills.” They had started selling Wankel based cars in 1969, and had built 300,000 so far, believing they would sell 60,000 in the U.S. in 1972.

The new Mazda RX-3 had a 90-horse Wankel, while the new 808 had a 70-horse conventional four-cylinder. The RX-3 cost $550 more (a hefty amount in 1972), though, and had poor fuel economy, shuddering on low-speed coasting, violent backfires, and stalling when cold. When Road & Track compared the RX-3 with the Mercury Capri V6, which cost $100 less, they found that the Capri weighed another 270 pounds but ran 0-60 half a second faster (10.4 vs 10.9 seconds), had about the same quarter mile time (17.7 vs 17.8), and yet achieved an extra 6 mpg over the RX-3 (24 vs 18).

Chrysler bought Mazdas with the Wankel engines, and with just 20,000 miles already found backfiring, short spark plug life, and emissions control issues. They interviewed Mazda owners and found them to be “a special group” happy with their cars but complaining about gas mileage; they expected 25-35 mpg and got 18, with some under 15. While more West Coasters know about Wankel engines (61% vs 31%), they were less interested in them (24% vs 37%, of those aware).

Smith summarized,

In its current (Mazda) state of development, the Wankel engine is finding a significant specialty/enthusiast market which may or may not persist; however, it is not demonstrating an ability to challenge the piston engine in a general market, because its unique qualities are not sufficiently redeeming to offset its current penalties, particularly its high cost and poor fuel economy.

He added parenthetically that Daimler-Benz, which had licensed the design in 1961 and done a great deal of R&D, gaining numerous patents, with three and four rotor prototypes, publicly said that the Wankel would be a curiosity until the penalties of the design could be fixed.

The mighty General Motors, largest automaker in the world, bought a license in 1970. Smith observed that they “plunged into the Wankel pool with little preparation but with supreme confidence in their ability to quickly swim where their predecessors had long struggled to keep afloat. Subsequent events appear to be drifting them to a more realistic attitude.”

Their effort brought in eleven divisions of the company, as well as parts suppliers and machine tool makers; and they sought advice from older license-holders. However, the Vega GT, which had been planned as a Wankel-only car for mid-1973, was pushed back to 1975, and the Wankel engine turned into an option—expected to be an expensive one, produced by the transmission group in Ypsilanti, with an aluminum housing. “The low-cost high-volume Wankel, originally anticipated for an innovative 1975 compact-size model with front-wheel drive, is still an enigma.” The engine plant originally meant for the low-cost Wankel was re-allocated to four-cylinders. Ford, meanwhile, did gain a license, but also gained an exclusive license for Stirling engine development.

Smith did not hold back for his second conclusion:

As for what Chrysler should do, Smith saw two choices; one was simply buying Wankel engines from a licensee, as AMC had agreed to buy Wankels from General Motors for the AMC Pacer (and had to make a small inline-six fit into the space earmarked for a Wankel, which made repairs more complicated). Mitsubishi was working on buying Mazda Wankels, and Toyota was reported to have a contract already. Comotor S.A., a joint venture of Citroën and Audi-NSU, was licensed to make Wankels and sell them to others, and had a 115-horsepower unit slated to start in 1973. These could be used in Rootes or SIMCA cars (both companies were owned by Chrysler) and brought over to the U.S.

However, before any of that was done, Smith warned that Chrysler should have a good view of the competitive picture, specific product and marketing plans, a study of sources of engines, results of license negotiations, and discussion of other future powerplant alternatives and whether they would obsolete the Wankel. GM, for example, saw the Wankel being replaced by gasoline turbines by the 1990s.

Smith also saw pollution standards as an issue that would kill Wankel engines—and piston engines, too, leaving only gasoline turbines and possibly newer technologies: “the Wankel bug has been generating an extraordinary amount of creative endeavor and many able inventive-types have dedicated themselves to the creation of even better mousetraps.” These included the Sarich Rotary Engine from Perth, Australia, and the Karol Rotary Engine from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. “These engines are very unlikely to measure up to such extravagant claims; but on the chance that there may be something new under the sun, we should be taking a look at them. The cost to look would be negligible; the fact that we are unencumbered with a Wankel license would be an advantage; and, the potential payoff could be staggering.”

Finally, he noted that a Wankel program providing 300,000 engines per year could cost over $100 million, and a turbine program for 750,000 turbines a year could run to $300 million. “Obviously, we should take a good look before we leap.”

His final conclusions:

At this point in time, we should not commit to the license proposal offered by Audi-NSU. If we did, our next move would be to field a traveling team of information collectors, who would go calling on the established Wankel club members. They would bring back seeds of design and manufacturing knowledge which would fall on the barren fields of a non-program and, with the passage of time, would slowly grow obsolete. Admittedly, if we pass now, the price of a license might go up, but it also might go down. Let’s take a chance.

On the other hand, we should hedge against a GM Wankel breakthrough by beginning to get ready for the possibility of a make-or-buy decision, as outlined above. And, in addition, we should step up our activities relating to the non-Wankel engine alternatives, particularly the gas turbine engine.

What happened, in the end? Electronic fuel injection pushed piston engines well beyond the needs of any emissions standards foreseen in the 1970s, while boosting fuel economy and power. By 2020, buyers could get a 797 horsepower full-size car that beat the fuel economy of that 90-horsepower Mazda RX-3. Jack Smith had been right again—with style and panache.

Product planner Burt Bouwkamp wrote:

Your recollection about the Wankel engine reminded me that Riney Bright and I met with Curtiss Wright around 1970. Riney arranged the meeting, and I was involved because as Director of Product Planning I reported directly to John Riccardo, who was President then. We did not have a VP of Product Planning until George Butts was promoted to that job.

Riney was exploring getting a license for the Wankel design; I think Curtiss-Wright wanted $50 million for the rights to it. After the meeting, Riney and I recommended to John Riccardo that we do it, but Engineering VP Alan J. Loofbourrow, who was not at the meeting, was strongly opposed. Loof’s reasoning was that the Wankel thermal efficiency could never be as high as a piston engine because of the high surface-to-volume ratio of the combustion chamber.

Loof’s position gave John Riccardo a reason to say “no” to an expensive proposition. In hindsight, Loof was right. A friend of mine (Chuck Woodruff, Mecosta County Prosecuting Attorney) had a Wankel-powered Artic Cat snowmobile; I thought of Loof’s position whenever I saw Chuck’s snowmobile at night because the exhaust manifold was cherry red, even at idle! Chuck was also the first one to need gasoline when we went cross-country.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos