The year was 1929, the economy was booming (until October), and the Chrysler car was well-established, having been brought out in 1924. The old Maxwell-Chalmers had become Chrysler Corporation in 1925; the Maxwell name had been retired that same year. In 1928, the company had added three divisions—creating DeSoto and Plymouth, and buying Dodge Brothers, a much larger company than Chrysler itself. Engineers quickly started upgrading the Dodge Brothers cars, which slotted between Plymouth and DeSoto.

The country’s leading automaker was General Motors, which had been created by a series of mergers under a man who may, in the 1920s, have been the nation’s most extreme combination of lovability and incompetence, Billy Durant (who had also been the force behind the Chevrolet, along with Louis Chevrolet himself).

To help its salesmen, in late 1929, Chrysler Corporation published a confidential comparison of their company’s technologies to those of General Motors’ various brands. This story is a snapshot of 1929-1930, and a summary of that supplement.

Chrysler had a good 1929, as did most automakers, in the boom times just before the stock market crash which kicked off the Great Depression. The company sold a record 450,543 cars, a big boost over 1928—since they had purchasd Dodge Brothers on July 31, 1928. Chrysler killed the four-cylinder Dodge Brothers engine; their engineers increased power in their smaller six cylinder engines, and added shock absorbers to the base cars.

| 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debt (in millions) |

$59 | $50 | $48 | $44 |

| Revenue (in millions) |

$315 | $375 | $208 | $184 |

| Sales | 192,083 | 450,543 | 269,899 | 272,118 |

| Dividends (in millions) |

$12 | $13 | $11 | $4 |

Buying Dodge meant Chrysler took on $59 million of debt, in addition to its existing $1 million. By the end of 1929, Chrysler had $50 million in debt, but given their high profitability, it was manageable, and it’s unlikely anyone at the company regretted the purchase. Steadily, despite diminishing revenues and continued dividends, Chrysler paid down the debt.

Chrysler had also opened up a new engineering building, with laboratories and prototype manufacturing spaces, in July 1928. Walter P. Chrysler was chairman of the board, Fred Zeder was VP in charge of engineering, and Carl Breer and Owen Skelton were executive engineers.

The comparisons highlighted Chrysler’s greater centralization around core technologies, as compared to the diverse General Motors (GM). Chrysler had its core engineering center, and all its divisions shared most of their technologies. The comparison is a bit misleading, because it treats its individual car models to be comparable to GM divisions; Chrysler only had four nameplates (Plymouth, DeSoto, Dodge, Chrysler) but the chart quotes eight, by splitting off the Dodge Six from the Dodge Senior (which seems unnecessary), and by counting the four Chrysler cars (66, 70, 77, and Imperial) as separate brands for this comparison though they shared far more than not.

The comparison was dated August 1929—but referenced the Chrysler 77, which was a 1930 model, and mentioned rubber engine mounts on the Dodge Brothers cars, so it almost certainly referred to 1930 model-year cars. (The Chrysler CJ is not included, coming out in mid-1930—it had four main bearings in its engine, not seven.) The GM models may have changed between August 1929 and the 1930 model year.

| GM | Chrysler | |

|---|---|---|

| L head | Pontiac, Olds, Marquette, Oakland, La Salle, Cadillac | All |

| Valve-in-head | Chevrolet, Buick | |

| Horizontal valve | Viking |

Chrysler also used aluminum alloy pistons in all engines, with the six-cyinders having aluminum-alloy piston struts. At GM, cast iron pistons were the norm, with Oakland using “semi-steel.” Likewise, all but one Chrysler engine used exterior oil filters; GM’s score was six with filters, three without.

| GM | Chrysler | |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum pistons | None | All |

| Cast iron | All but Oakland | |

| Semi-steel | Oakland |

The number of crankshaft bearings varied. At GM, Chevrolet, Pontiac, Viking, La Salle, and Cadillac had three; the other brands had four. Plymouth had three, De Soto had four, and Dodge and Chrysler had seven.

At GM, Chevrolet and Olds had crankshafts without counterweights—as did Plymouth, Dodge, and the Chrysler 66.

Spark control at Chrysler and GM was semi-automatic—except for Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Oakland, where it was fully automatic (arguably, semi-automatic spark control could be handy on steep hills). Every engine used oil pumps except at Chevrolet, which still had old-fashioned “splash” lubrication. Chevrolet, Buick, and Plymouth were the only divisions in this comparison to use gear-type camshaft drives rather than timing chains.

A major advantage for Chrysler was the company’s hydraulic brakes, common to every division. At GM, all cars had mechanical brakes. Chrysler’s handbrakes acted on the driveshaft; at GM, two divisions did the same, two acted on all wheels, and the rest only acted on the rear wheels, with a mix of interior and external mechanisms.

| Hand brake | GM | Chrysler |

|---|---|---|

| Driveshaft | Pontiac, Oakland | All |

| All wheels | Marquette, Viking | |

| Rear wheels | All other GM |

All Chryslers used Timken bearings for the front and rear wheels, and for the differential; at GM, only Cadillac did so, with La Salle having Timken bearings for the differential but not the wheels. Most of the GM cars had ball bearings, with some using Hyatt bearings for the rear wheels only; all GM brands but Cadillac used ball bearings for the differentials.

Chrysler was known for its rubber engine mounts; by 1929, GM had largely caught up, with only Chevrolet and Pontiac lagging behind. Likewise, Chrysler had standardized entirely on Hotchkiss final drives; at GM, Chevrolet, Buick, and (oddly) Cadillac still used torque-tube designs, though the other brands had updated to Hotchkiss designs.

Chrysler used single-plate clutches with ball release bearings; at GM, Buick, La Salle, and Cadillac all used multiple-disc clutches, while Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Marquette had bushing-type clutch release bearings.

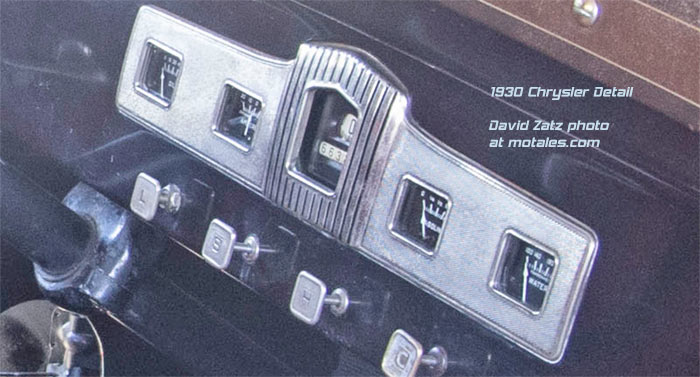

Finally, there is one item most modern-vehicle owners don't know about, for good reason: the dashboard-mounted manifold heat control, which adjusted the amount of engine heat getting to the carburetor. This was replaced by other systems later, but the idea was that on cold starts and on cold days, the carburetor did a better job of vaporizing fuel if it was warm. The driver could, from inside the car, control whether manifolds directed heat to the carburetor—but not on the Plymouth, Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, or Marquette.

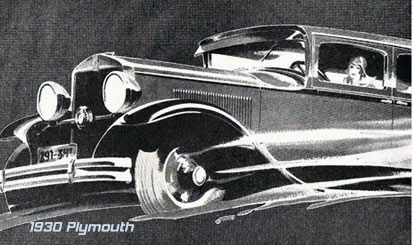

In 1929, Plymouth made its Model U, which was similar to the original Model Q, and which was directly descended from the Maxwell. The Model U’s main changes from the Q were dropping the Chrysler name badge, changing the headlights, and a new bumper design. The body was metal-over-wood, with wood wheels (or optional wire wheels). The Model U engine was upgraded somewhat from the Model Q, but it had the same power rating; and it had rubber engine mounts, the first on any low-priced car. The Model U continued production into April 5, 1930, before giving way to the 1930 30U. On July 1, 1930, Plymouth switched to the 1931 model year.

While the 30U’s styling was quite similar to the U, mainly involving a wide chrome radiator shell and a horn on the headlamp bar, according to Jim Benjaminson, it switched to an all-steel body—following, in order, Dodge Brothers and Ford; this occured after the comparison chart was written. Other changes were made as time went on, likely to support lower prices, such as switching from chromed to painted headlight assemblies. The 30U’s engine bore was expanded by a quarter of an inch, adding 3 bhp (the larger engine is shown in the chart further down this page). Fuel tanks replaced vacuum tanks around July (for the 1931 model year), and water pumps replaced thermo-syphon cooling sometime early in the production run.

Plymouth sales rose partly because the company had built a huge new plant at Lynch Road and Mount Elliott Avenue in Detroit, which had been started in October 1928 (and which may put to rest the oft-quoted idea that Chrysler bought Dodge Brothers to have a bigger factory for making Plymouths). 1929 Plymouth U sales beat the 1928 Q by 50%; the price, without delivery, started at $655.

Plymouth literally doubled its sales in 1930, partly due to a price drop so the cars started at $535. Plymouth finished 1929 in the #10 spot in U.S. sales; in 1930, they were #8. Walter Chrysler had already authorized—after the stock market crash—a $2.5 million project to create a completely new Plymouth, the PA, which ended the last remnants of Maxwell engineering. His vision panned out. and Plymouth would take third place in sales for 1931. That sales boost was partly helped by Walter Chrysler’s adding Plymouth to the Chrysler, Dodge, and DeSoto sales networks in 1930.

The Plymouth 30U, despite being a four-cylinder, lent a good deal of its parts to the six-cylinder DeSoto CK and Chrysler CJ, which also helped those divisions to weather the Depression relatively easily.

Dodge Brothers had two car lines for 1929, the Six and the Senior—both powered by six-cylinder engines. Until 1927, there had never been a Dodge with more than four cylinders; in 1927, they had a new 224 cubic inch six (60 bhp) in addition to the four-cylinder; and in 1928, they were six-cylinder-only. The Six started at $995 in 1929.

Dodge Brothers gained a new straight-eight car in January 1930, with the kind of timing long associated with Chrysler and its successors; the six cylinder continued as well. The eight-cylinder had an all-steel body, a slanting windshield, and numerous premium features. During the 1930 model year, fuel pumps replaced vacuum tanks; ventilating windshields were added; and “Brothers” was dropped from the name. In response to the market crash, Dodge starting prices dropped to $835.

DeSoto’s first model year was 1929; the new car filled the gap between the $655 Plymouth and $995 Dodge (adjusted for inflation to July 2022 dollars, the brands’ 1929 prices would be Plymouth, $11,217; DeSoto, $14,471; Dodge, $17,040). The DeSoto Model K had a 175 cubic inch engine generating 55 bhp. For 1930, the series was essentially unchanged, but with a new straight-eight model (rated at 70 bhp) and a larger six rated at 60 bhp; the price dropped to $810. Both Dodge and DeSoto changed to the 1931 model-year as of July 1, 1930.

A new economy DeSoto, based on the Dodge Six (including wheelbase and engine), was launched in May 1930; its first model year had around three months of production before the ’31s started up. This is the DeSoto Six shown in the chart below.

* Road weight; DeSoto is almost certainly a typo and should be 3,161.

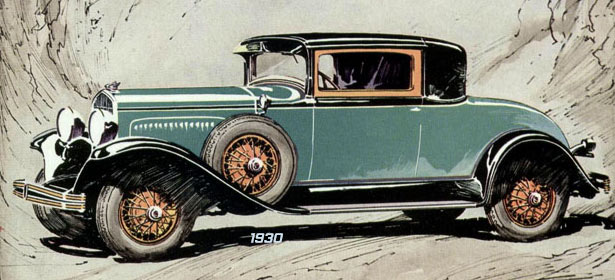

At Chrysler, 1929 brought slender new radiators, thermostat-controlled grille shutters, and sweeping fender lines; the line was powered by inline six-cylinder engines from the in-house engineering team of Zeder, Skelton, and Breer. The company had three models, including a new 75 (guaranteed to reach 75 mph), starting at $1,535; and the 65, starting at $1,040.

The 1930 models brought styling changes, fuel pumps instead of vacuum tanks, and new steering wheels; mid-run, power increases changed the Model 65 into the Model 66 (the Model 77 also had more power, but the top speed was apparently the same). A new model, the 1930 CJ, was downsized (Chrysler Junior?) using Plymouth parts; it still had the features people expected of Chrysler. The CJ sold for $795 to $925, well below the 66 (which ran from $995 to $1,095) and far from the 70, 77, and Imperial.

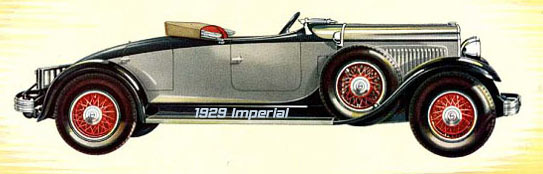

The high-end Chrysler Imperial, launched in 1926 as a 1927 model, also had a six-cylinder, generating 92 bhp—making it quite powerful by 1927 standards, and allowing a guaranteed top speed of 80 mph. The 1928 Imperial used higher compression to raise power up to 112 bhp, and the 1929 Imperial used slimmer radiator grilles. The 1929 Imperial started at $2,675—around $45,811 in July 2022 money. The 1930 model started at $2,995, adding automatic grille shutters and a four-speed transmission shared with the Chrysler 77. DeSoto and Dodge gained eight-cylinder engines, but Chrysler did not—and those straight-eights had less power than the Imperial’s six.

Despite buying the bigger Dodge Brothers in 1928, Chrysler Corporation was in good shape for the Depression; they quickly adapted by using Plymouth parts to produce downsized DeSoto and Chrysler cars at lower prices, while making the top-end Imperial model more attractive to those who were still willing to spend big on a powerful high-tech car. Under Walter P. Chrysler’s leadership, Chrysler drove into the Depression with justifiable hope for the future.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky