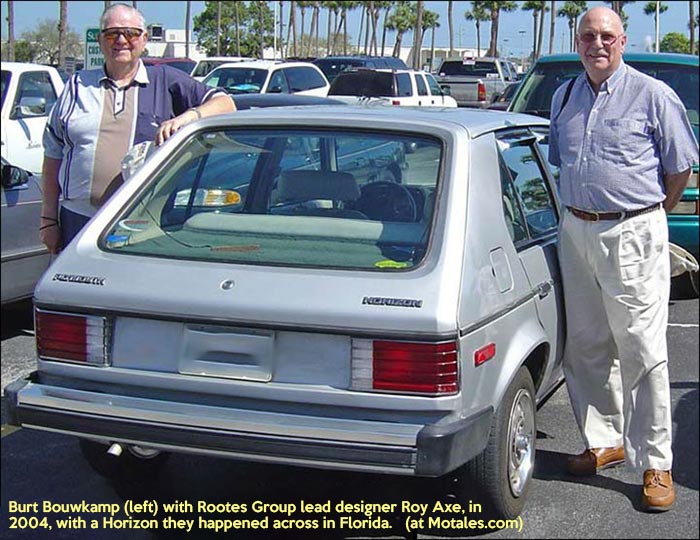

Burt Bouwkamp rose quickly through the ranks of engineering and then product planning; he led product planning for Chrysler Europe as they produced two Cars of the Year in rapid succession, and then went off to join Mitsubishi’s board of directors and be Chrysler’s man in Japan.

One secret of his success, he said, was “Keep your boss well informed of problems, but never bring a problem to him without a recommendation of what to do about it. Be sure that when you have a problem, you have a recommendation. You will shoot right up the ladder.”

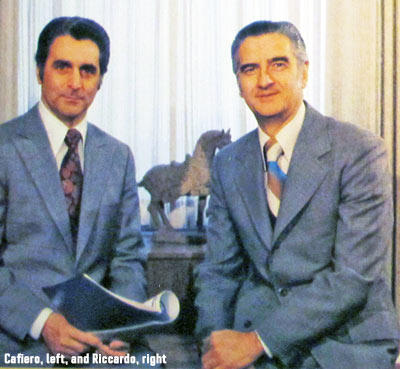

For two years, Burt worked for John Riccardo, who ran Chrysler Corporation.

John Riccardo did not have an easy job. He inherited a company that was in bad shape; for decades they had matched much larger companies product for product, rarely having the volume to compete well in any particular segment.

The company had ossified, though some jolts to the system—the Valiant cross-functional team in 1958-59, the arrival of a few highly advanced electronics experts from Huntsville, the engineers’ racing teams—had kept it from falling behind in technology. Chrysler had not managed its brands well; each one had spread to step on the others, without having a major differentiator in the public eye.

John Riccardo served at the pleasure of the board. Each quarter could seal his fate. He was not secure in his job, like Lee Iacocca would be; he most likely did not see himself as being able to stand his ground in front of the board, to take one of the many options (such as giving up market segments) that could have helped Chrysler to thrive.

While Burt Bouwkamp worked for John Riccardo, he was present at most of the meetings Riccardo went to—but he also went to other meetings, and heard many things Riccardo did not know about.

“One of the things that surprised me the most was that they played with money and timing,” Burt told me in 2021. They could take a bad quarter and move more bad news forward, so that the next quarter it would look as though they had improved more. A good year could be made better by moving money around and changing the timing.

The goal there was to make the reports look better, so for each quarterly or annual report, they moved money forward or back, to make themselves look good. It was almost certainly legal, but Burt admitted, “I thought it was cut and dried—that the numbers were the way they were.”

Burt said that, among the things he learned, was that one has to do the right thing, rather than doing the wrong thing well. His main regret is that he did not spend more time influencing Riccardo, instead working on carrying out his orders as well as he could. Riccardo continued the previous Lynn Townsend’s product plan; as Burt wrote, though, that “John didn’t have the experience to know that Chrysler did not have the financial and technical resources to compete car-for-car with GM. John thought we could outsmart GM and Ford.”

Later, he read in a book by Richard Nixon the slogan, “Engineers do things right. Leaders do the right things.” Burt told me that if he’d read that 50 years ago, he’d have hung it on a sign on his wall; because too often, he was an engineer doing things right, when he should have been a leader doing the right things.

Related: The 1972 report that could have saved Chrysler.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky