Cars made before electronic controls and emissions standards tended to be very simple under the hood. Routing was important for the spark plug wires, generator or alternator, battery, and fuel lines; there were precious few other wires, even if you had air conditioning. As time went on, though, automakers had to make things more complicated, both to wring more power out of their engines and to increase gas mileage while cutting pollutants.

By the late 1970s, the engine bay of pretty much any American car was a mess—a situation that continued into the 1980s, with hoses and wires criss-crossing the engine. Feedback carburetors, turbocharger vaccum controls, sensor connections, vapor recovery hoses, and other additions all conspired to make the engine area complicated and, sometimes, prone to problems as wires or hoses rubbed up against hot or moving parts.

Burt Boukwamp, former Dodge chief engineer and head of product planning, recalled that, when he was sent away to be Chrysler’s Man in Japan, Chrysler was launching its 1982 cars—and they were still doing the wires and hoses as they had in the past, with far simpler systems. Various groups designed the chassis and powertrain and body; then mechanics worked on a mockup of the engine bay and chassis, trying to make the wires or hoses as short as they could be. As Burt wrote:

Chrysler USA was slow in designing hoses and wiring in the original vehicle design. At the time, provision for wiring/hoses in the sheet metal was designed as a change based on three dimensional mockups of routing of the wiring/hoses. We learned a lot from the Japanese (Mitsubishi Motors) on how to provide for hoses and wiring in the original sheet metal and plastic designs.

What was happening under the hood was important, but it wasn’t really engineered early in the process for some time after that, which made for some odd arrangements. It also meant higher costs (more wire, more hose) and some problems over time. As time went on, engineers worked on these issues more carefully.

According to former engineer Steve Zink, Chrysler first committed money to under-hood fit and finish with the K-cars.

The next step was engineering the wires and hoses electronically, with Chrysler’s CADCAM software or Dassault’s CATIA. Still, the engine area was created with little thought for how it might look, other than a painted valve cover or branded air cleaner cover. The idea of truly styling the entire area under the hood may have had its genesis in a trip to Italy.

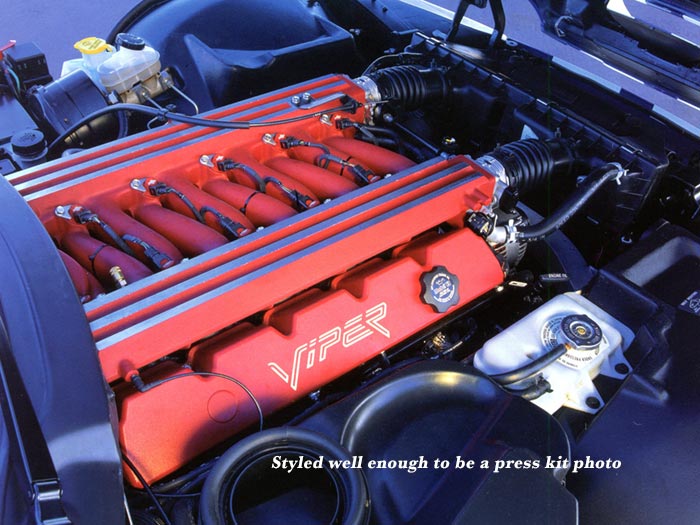

At the turn of the decade, Chrysler tried to have its captive automaker Lamborghini develop an aluminum version of the upcoming V-10 engine for the Viper. Lamborghini’s design was unsuitable for Chrysler (high cost, heat issues in traffic, and such); but it had been carefully styled as well as engineered. That made an impression on the Viper team, and they tried to maintain the appearance of the packaging even as they made it more practical for a street car.

To quote the definitive book Dodge Viper, “everyone liked the way the engine looked, and [Team Viper] kept as much of Lamborghini’s styling as it could, along with Lamborghini’s external coolant manifold. That was, essentially, a cast passage outside each cylinder bank, with pipes for each cylinder; after cooling the cylinders, coolant went to the heads and then returned to the radiator.”

Today, every manufacturer plans every millimeter of underhood space from the start; computer design software not only optimizes placement for cost, but also measures heat and wear from rubbing against other parts, physical interference, and such, while mechanics are often brought in to advise on routings which will get in their way when doing maintenance or repairs. It’s a completely different ballgame.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky