Chrysler tried to compete against GM and Ford on every front from the 1950s through the 1980s, though they increasingly didn't have the resources to do it. Finally, the company acquired AMC in 1987, and adopted that smaller company’s approach to engineering.

There was no way Chrysler could keep developing the new vehicles it needed on its own. They adopted three solutions: moving to cross-functional teams for development, which slashed expenses; asking suppliers to provide ideas for cost-cutting; and leaning more on suppliers to develop large parts of their cars, a system used by AMC to a degree, but best known from its use in Japanese kieretsu.

The Extended Enterprise, in short, brought suppliers in as though they were part of the company; it required a great deal of trust, but cut cost and development times considerably, while increasing quality, without compromising the product. To make this work fully, they needed to have multiple supply chain companies working together, with, in Chrysler’s words, “effective communication, common visions, and mutual trust.”

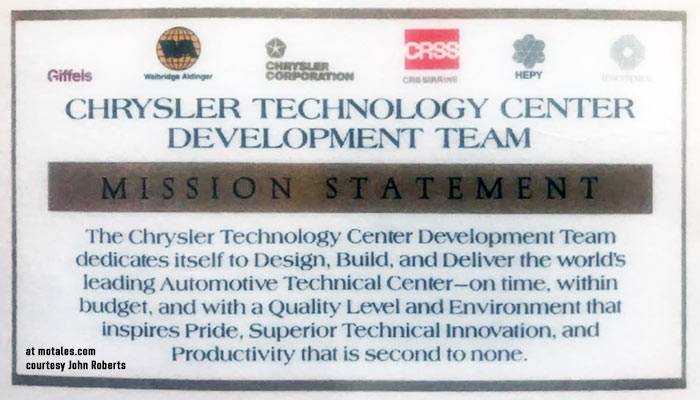

Tech Center team and mission statement included key contractors—part of the extended enterprise

Chrysler had to make a 180° shift from being strict with suppliers and watching every penny, to providing suppliers with higher profits as long as suppliers cut overall costs. In at least one case, overall cost was sacrificed in favor of a better product: in the second-generation Neon, the supplier was able to throw in traction control (which was unusual at the time) for barely more than the cost of antilock brakes. In another case, Chrysler piggybacked on Motorola’s internal shipping; Motorola had been sending empty carriers back from its Texas plant to a supplier in Chicago, and now carried parts most of the way back to Chrysler’s north-central plants.

IT had to play a major role to reach the goal; they provided an “extranet,” and worked with suppliers on switching to Dassault’s CATIA—which had been tailored to Chrysler’s needs. They also helped with supply chain mapping, describing the full process from raw materials to car dealerships. IT worked out a way for suppliers to provide their own supply chain maps and integrate them with Chrysler’s maps.

To protect Chrysler’s interests, the Extended Enterprise system measured quality, cycle time, and technological innovation. Total systems cost replaced the price of individual parts, because the goal was to cut the cost of the entire car, including labor and other assembly costs.

The system worked well until Daimler took over; a few years afterwards, demands for across-the-board cost cuts returned, and those who had gambled on a new plant in Brazil were told to take the loss when it was abandoned. By 2003, Chrysler was back to bullying suppliers, and payments for cost reduction were gone. There was never a problem with the Extended Enterprise concept, but new executives meant a new strategy, one which would result in numerous rounds of cuts and layoffs, culminating in bankruptcy and, eventually, a new beginning with Stellantis.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos