When Chrysler bought American Motors in 1987, they gained AMC’s head of engineering, Francois Castaing—and quickly put him in charge of the bigger company’s engineering. Castaing insisted on new engines—a four-cylinder, a V6, and two new V8 families, the second of which was the “Hemi.” Without Castaing, it’s unlikely Chrysler would have made the sophisticated 3.5.

Spark plugs were in the center of the combustion chamber, semi-Hemi style. The distributor was banished in favor of coil packs. The new engine was quite powerful for 1993, with 214 horsepower and 221 pound-feet of torque; it was also reliable, but it required 89 octane “midgrade” fuel. It had an iron block and single-cam-per-head design despite its 24 valves. Before long, Chrysler was working on a smaller, more optimized engine—the 3.2. This 3.2 liter SOHC V6 was based loosely on the 3.5 V6, but it:

A smaller version of the 3.2, developed alongside it, was launched at the same time, replacing the old, pushrod-based 3.3 liter V6 engines in Chrysler and Dodge cars—but not in their minivans.

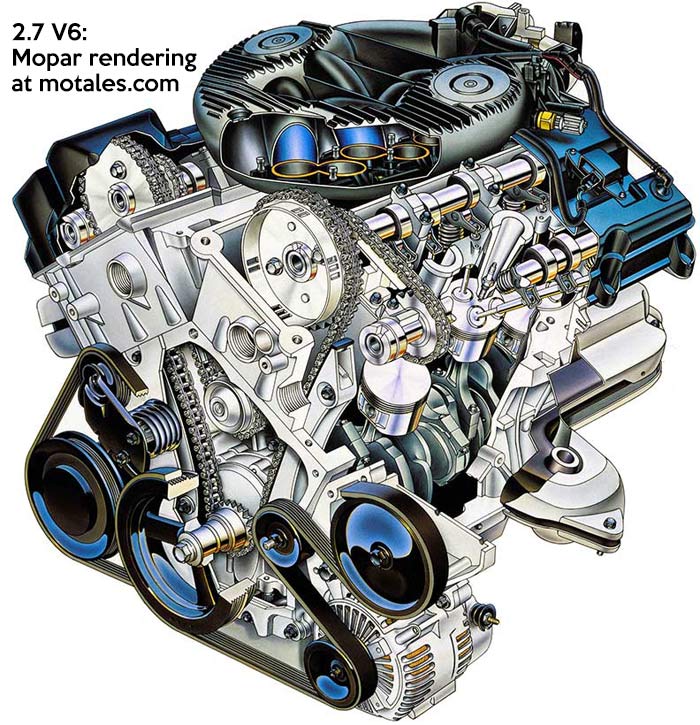

Released in 1998 along with the 3.2, the new 2.7 was small for an American V6; it remains the smallest V6 made by Chrysler or FCA US. Francois Castaing meant it to be both a statement—that Chrysler could engineer a powerful small engine that matched the best in the world—and to produce superior fuel economy with lower weight. It was also the only V6 produced by Chrysler until the Pentastar series which had dual cams in each cylinder bank.

The 2.7 had its own block with smaller cylinder spacing (104 mm) and deck height (210 mm) than the 3.2 or 3.5; for that reason, while its basic design came from the 3.2 V6 (which in turn was derived from the 3.5), longtime engine creator Willem Weertman considered it to be a brand new family of its own. The block was cast aluminum with iron bore liners cast in place; the liners were a cheap way to provide excellent wear resistance, and worked extremey well (alternatives such as hardening the aluminum were far more costly and did not provide any advantages other than possibly a slight weight difference).

The combustion chamber, like those of the 3.5 and 3.2, used a “Hemi-style” pent-roof design with center spark plugs. Exhaust valves were 32° from the intake valves, and measured 33.8mm (the intake valves were 27.8mm). Stamped steel rocker arms, with roller followers, were similar to those of the “Neon” dual-cam four-cylinder.

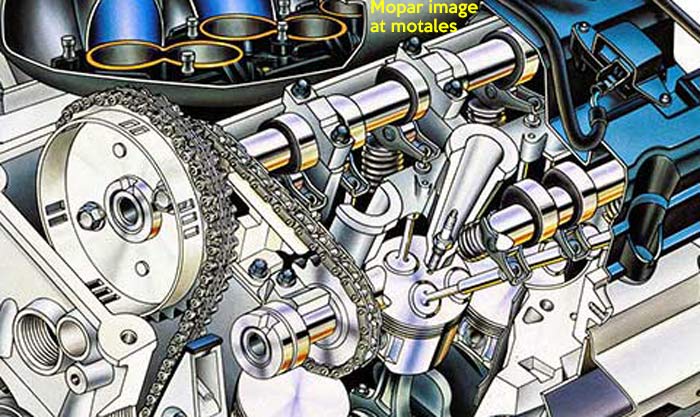

The 2.7 had a version of the 3.2’s new multiple-length intake system; but it was a true dual-cam design, with twin cams in each head, unlike the 3.2 or the 3.5. The intake and exhaust valves were driven by separate camshafts, made of steel tubing (hollow) to cut weight; most past cams had been solid and quite heavy. Lobes were hardened steel. Roller chains with tensioners connected the intake cams to their exhaust cams.

The engine had six attaching bolts for each of the four main bearing caps. Some of these bolts were also used to attach the windage tray, which itself did dual duty as a stabilizer for the four main bearing caps.

The timing chain drove the water pump, while the oil pump was driven directly by the crank. This new engine used a timing chain rather than a belt, so it was not a non-interference design—if the chain broke, the valvetrain was killed, too. The heads and block were extended to provide space for the chain.

Regardless of year, the 2.7 used coil-on-plug ignition and sequential multiple point fuel injection.

Power output per liter (or per cubic inch) was the highest of any Chrysler V-engine, 74 hp/liter—close to the 2.0 DOHC’s 75 hp/liter. At its 1998 launch, the compression ratio was 9.7:1, with 200 hp (149kW) at 5,800 rpm and 190 lb-ft (258 Nm) at 4,850 rpm. The engine weighed 337 pounds, and debuted in the 1998 Chrysler Concorde and Dodge Intrepid.

A Magnum version had the variable intake system which built on Chrysler’s V8 engine tuning work from the 1950s and 1960s. A solenoid valve varied the effective length of the intake manifold to create a supercharging effect at different engine speeds. The advantage of the new system was that having the air tubes at any particular length made more power at one engine speed but cut power at another. This system could provide supercharging at more than one engine speed range.

Both regular and Magnum engines used reinforced nylon intake manifolds. These were lighter and smoother than iron or aluminum intakes. The engines had a single throttle body, with electronic throttle control.

The 2.7 V6 engine reduced noise with:

Early 2.7 liter engines could turn oil into “sludge,” causing engine failure—a problem which was somewhat common in the auto industry at the time. Chrysler quickly pinpointed the crankcase ventilation system as the root cause, because hydrocarbons were entering the oil and breaking it down there. This problem was solved sometimes around 2002-2003.

The sludge could be seen on the dipstick and in the PCV valve. Eventually the oil light would start flashing, and the engine would start ticking, running eratically, and stalling. Randy from Allpar wrote that the main problem was the water pump gasket leaking coolant internally, diluting the oil. Chrysler resolved this issue by changing the gasket from a metal separator plate with a silicone-like sealing surface, to a more conventional one with a revised water pump. The issue had to be addressed immediately.

This issue was made worse by the fact that water pumps could be replaced without changing the separator plate, because it looked like part of the engine. In addition, some water pump kits had the cam sensor notch in the wrong place, so the engine wouldn’t start after it was replaced. Randy felt this contributed to the 2.7’s bad reputation—which was undeserved after the first couple of years.

Oil can be sent to a lab to check for contamination.

In 2004, the 2.7 liter engine was modified in large cars (LX series—300, Challenger, Magnum) for better low-speed torque. This dropped the peak power ratings to 190 hp at 6400 rpm, and 190 lb.-ft. of torque at 4000 rpm. The retuning mainly used a new active dual-plenum intake manifold. The active part was the tuning valve, which could increase part-throttle torque by up to 10% in the primary driving range of 2100 to 3400 rpm.

The “LX cars” also added electronic throttle control, or “drive by wire,” which helped with pollution control and made for better experiences with cruise control, especially in hilly areas; it worked with the transmission controls, too, to reduce gear hunting. These changes all made their way to the 2008 Sebring/Avenger midsized cars and the 2009 Dodge Journey.

Chrysler was late to the variable valve timing (VVT) party, though they competed well without it. By 2005, it was clear that VVT was an important technology, Chrysler had started work on a VVT-equipped 2.7 liter V6—not production intent, but a project of the Advanced Engine Testing group.

Lab technician Marc Rozman and engineer John Opra tested the VVT 2.7 V6. A good deal of work was needed, both physical and in software; at one point they even tested swapping in Honda cams, along with other Mopar cams. They were able to boost power, but eventually they ran out of time or learned all they could learn. The 2.7 VVT was taken out of testing after around 21 months, replaced by the turbocharged 2.4 four-cylinder.

| Vehicle | Engine | BHP | RPM | Octane | Cost As Tested |

| Intrepid/Concorde, 1998 | 2.7L | 200 | 5800 | Regular | $21,000 |

| Acura 25TL, 1997 | 2.5L | 176 | 6300 | Premium | $30,478 |

| Intrepid/Concorde, 1998 | 3.2L | 220 | 6600 | Regular | $24,000 |

| Ford Taurus, 1996 | 3.0L | 200 | 5750 | Regular | $24,205 |

| Cadillac Catera, 1997 | 3.0L | 200 | 6000 | Premium | $34,750 |

| Nissan Maxima, 1997 | 3.0L | 190 | 5600 | Regular | $24,675 |

Above: from press kits, sorted by output per liter. Below: from the EPA, not really sorted; automatic transmissions.

| 1997-98 Cars | MPG | HP | Fuel |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 Intrepid 3.2 | 18/28 | 220 | Regular |

| 1998 Intrepid 2.7 | 21/30 | 200 | Regular |

| 1996 Taurus | 20/29 | 200 | Regular |

| 1997 Maxima | 21/28 | 200 | Premium |

| Category | 2.7 Original | 2.7 Revised* | 3.2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bore x Stroke | 3.39 x 3.09 (86 x 78.5mm) | 3.66 x 3.19 | |

| Compression | 9.71:1 |

9.9:1 | 9.5:1 |

| Horsepower | 200 @ 6000 |

190 @ 6,400 | 220 @ 6600 |

| Torque: lb-ft | 188-190 @ 4900 |

190 @ 4,000 | 222 @ 4000 |

| Redline | 6464 | 6,600 | 6800 |

| * 2004 for large cars, 2007 for all cars. | |||

Emissions rules were dealt with by one or more three-way catalytic converters, heated oxygen sensors, and exhaust gas recirculation (EGR); they met California’s ULEV 1 specifications.

The 2.7 liter engine was never a fan favorite, despite its power ratings, which were well above those of the 3.3 it replaced. It never quite got over initial impressions from sludge and lack of low-end torque (addressed in updated tuning). Starting with the 2011 cars, it was phased out in favor of the Pentastar V6, which used variable cam timing and replaced all Mopar V6 engines with a single basic design.

In 2018, Kevin Haddock suggested the following process, which we have not checked for accuracy, in response to a question about replacing a worn timing chain:

“Those are great motors if treated right.”

Sources: Willem Weertman, Chrysler Engines, SAE; Allpar.com; Press kits, 1998-on; Kevin Haddock on allpar.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky