Chrysler Corporation was not the first company to use hemispherical heads in their engines, but their high production levels and high performance—along with trademarking “Hemi™”—have linked Chrysler and Hemi engines in the public mind.

In the 1930s, Chrysler was seeking the most efficient engine designs to replace their in-line engines; they even tried sleeve-valve and radial setups. World War II halted the search, for a time, and they stopped working on a straight six replacement until 1958.

During the war, Chrysler developed a new inverted-V16 engine for aircraft, a 36-liter monster dubbed the XIV 2220 (2,220 cubic inches). A test P-47 Thunderbolt reportedly broke 500 mph with this prototype, adding 70 mph to the top speed of the prior engine, created by a company whose main business was aeronautics. Five engines were made; the locations of three are still known. This project ended because jets made propellor-based fighters obsolete; but it gave the engineers more experience with hemispherical heads, which they also explored in an experimental V12 tank engine.

What makes something a hemispherical (in Chrysler’s case, a Hemi™) engine? The differentiator is having a hemispherical (half-a-sphere) shape in the head; this brings the spark plug to the dead center, with a valve on either side. That makes combustion more efficient, because the flame starts in the center of the area, and allows for much larger valves, bringing higher-than-usual airflow. Welch was likely the first outfit to use hemispherical heads, but many others followed before Chrysler—which was likely the first company to mass-produce hemispherical heads on large engines.

After the war projects, Chrysler engineers renewed their search, methodically using single-cylinder test engines to create different cylinder head and valve arrangements. The team, drawing heavily from the aeronautic engine group, included engineering chief Fred Zeder's younger brother, James Zeder; Mel Carpentier, head of engine design, soon succeeded by William Drinkard; Ev Moeller, who in 1939 was an early graduate of the Chrysler Institute; and Ray White. John Platner was in charge of testing every setup they could find (including designs from Rolls-Royce, Fiat, Riley, Alfa Romeo, and Healey) on the single-cylinder engine; he found that the hemispherical heads used by Riley and Healey produced more power than other setups, while avoiding spark knock, because it could produce high power at low compression. The valve life was also longer. He and R. Dean Engle wrote these findings in a October 1947 report.

James Zeder took the next step, trying out hemispherical heads on a Chrysler Six. The modified engine was smoother and produced much more power, but it cost more and was more complex, requiring dual overhead cams. Indeed, the need for twin cams was the main issue with hemispherical-head engines, and the main reason, most likely, why they were still a niche design around the globe. Twin cams greatly increased cost, complexity, and tuning time.

Willem Weertman wrote in his definitive book Chrysler Engines that the Powerplant Research and Engine Design teams worked together to make a Hemi engine with a single cam; they worked in both V6 and V8 forms. Increasing bore size would allow larger valves, and the compact shape of the V-engines, compared with Chrysler’s existing inline engines—especially inline eights—would improve car layouts by dramatically shrinking the engine bay.

The V8 was a bit of a hard sell to the executives, because Chrysler already had a smooth, reliable in-line eight-cylinder whose tooling had long been paid for. Bill Drinkard and John Platner argued that the engine would be a major breakthrough, and it was approved. (One story has James Zeder, in charge of powerplant, getting permission from his legendary older brother, Fred Zeder, who was the head of Engineering; Fred was opposed to V8s, but the president of Chrysler overruled him because GM was working on V8s.) In any case, Mel Carpentier assigned design of the actual production engines to Fred Shrimpton.

The first V8 was a small model to test the idea, created in 1948; it worked well enough that management green-lighted a full prototype, displacing 331 cubic inches and dubbed the A239. Drinkard set a standard for 100,000 miles before any major parts would need to be replaced; years later, many still thought engines should only last 50,000 miles.

The valve loading made camshaft wear a major issue, with the cams sometimes lasting only half an hour. Fixes included using different materials, coating the tappet face, changing cam profiles to help rotate the tappets, and adding ZDDP to the break-in oil. Without these steps, taken by future racing chief Bob Rodger and future product planner Burton Bouwkamp among others, the “Firedome V8” would never have reached production.

The team also had to figure out how to change spark plugs, an annual chore, without removing the valve covers; they eventually came up with the idea of a steel tube going through the valve cover, with the spark plug protected by a ceramic boot and the tube sealed against oil by an O-ring. Another cover protected the spark plug tubes and wires, which were routed to the back under the cover, giving the engine an unusually clean look.

The engineers shot-peened the crankshaft for durability, and developed hydraulic tappets to increase valve life; Carter and Chrysler engineers worked together on a water-jacketed carburetor to prevent icing and stalling, including a built-in automatic choke.

Chrysler had one engine as an exclusive, but DeSoto and Dodge were told to propose their own versions. Plymouth, the mass-production brand, was not granted a V8, which was hardly surprising given the high cost of making the V8s.

Though all the engines were made from the same family and even penned by the same person, they all had different internal parts, so DeSoto, Chrysler, and Dodge Hemi internals are often not interchangeable.

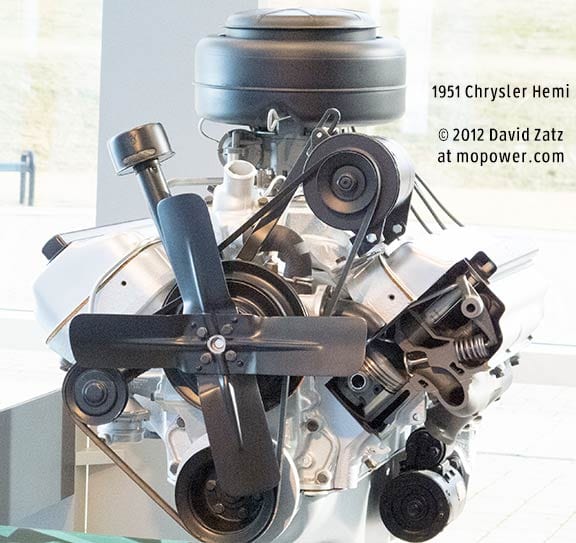

The first Chrysler Hemi—then called a “dual rocker” by the engineers, and dubbed Fire Power by Chrysler—was standard in the 1951 Chrysler New Yorker and Imperial, optional on the Saratoga, and not available on the Windsor. Generating 180 gross horsepower and 312 pound-feet of torque with 7:1 compression, it beat the Cadillac V8 by a full 20 horsepower, though Cadillac being substantially above Chrysler in cost; and it had lower compression than the Cadillac engine, so it should have been less powerful but could run on lower-quality gasoline. Both engines were 331 cubic inches in displacement, showing the advantage of the hemispherical-head design.

The Hemi-powered Chrysler Saratoga ran a 12-second 0-60 run, easily beating Cadillac (13.5 seconds) and Oldsmobile (12.5 seconds), not to mention any Ford. The quarter mile came in 18 seconds at 82 mph, and the Chrysler New Yorker was the Indy 500 pace car.

It had a 3.81 inch bore and 3.63 inch stroke; the intake valve was 1.81 inches and the exhaust valve was 1.5 inches in diameter. Rockers rode on twin shafts, hence “dual rocker.” The idea behind the short stroke was to have slower piston speeds for longevity. The pistons themselves went between crank counterweights at the bottom of the stroke to smooth the idle. The 1952 DeSoto version had 160 horsepower, and was put into around 50,000 cars; the 1953 Dodge version was 241 cubic inches and 140 horsepower.

| Year | Gross Horsepower and Torque |

|---|---|

| 331 Chrysler FirePower | |

| 1951-53 | 180 hp / 312 lb-ft |

| 1954 | 235 hp |

| 1955-56 | 250 hp |

| 1956 | 300 hp / 345 lb-ft (C300) |

| 354 Chrysler FirePower | |

| 1956-57 | 280 hp / 380 lb-ft |

| 1956 | 340 hp / 385 lb-ft (300B) |

| 1957 | 340 hp / 380 lb-ft (Dodge D-501) |

| 1957 | 295 hp |

| 1957-59 | Dodge pickups |

| 1956 | 355 hp (300B option) |

| 392 Chrysler FirePower | |

| 1957 | 325 hp (375 hp, 420 lb-ft in 300C) |

| 1958 | 290 hp |

| 1958 | 310 hp |

| 1958 | 345 hp |

| 1958 | 380 hp (2 x 4 bbl), 435 lb-ft |

| 1958 | 390 hp (EFI), 435 lb-ft |

| 1958 | 360 hp (Facel Vega) |

| Dodge Red Ram and Super Red Ram | |

| 1953-4 (241) | 140 hp / 220 lb-ft |

| 1955 (270) | 183 hp (245 lb-ft) or 193 hp (with Power Pack) |

| 1956 D500 (315) |

260 hp / 330 lb-ft (D500) 295 hp (D500-1) |

| 1957 D500 (325) |

285 hp / 345 lb-ft 310 hp / 350 lb-ft |

| DeSoto Fire Dome | |

| 1952-54 (276) |

160 hp / 250 lb-ft |

| 1955 (291) | 200 bhp / 274 lb-ft 185 bhp / 245 lb-ft |

| 1957 (341) | 270 hp / 350 lb-ft |

| DeSoto FireFlite | |

| 1956 (330) | 230 hp (255 w/4bbl) / 305 lb-ft |

| 1957 (341) | 295 hp (4-barrel) / 375 lb-ft |

| DeSoto Adventurer | |

| 1956 (341) | 320 hp / 356 lb-ft |

| 1957 (345) | 345 hp / 355 lb-ft* |

A 1952 Chrysler, despite a Caddy compression-and-power boost, still won the Daytona Beach speed runs. The first racing win, though, was done by Tommy Thompson on a half-mile dirt track (with a 250-mile race length). By then, James Zeder was in charge of Engineering; he brought in performance-minded engineers to get more power out of the engine.

The best showcase for the original Hemi was Bob Rodger’s Chrysler C-300, the first production car to have 300 horsepower, and the hottest car of the year; it cost nearly twice the price of a loaded Plymouth. The sheet metal was mostly shared with humble Chryslers, but there were clear indicators of what was under the hood, including color medallions.

Getting to 300 horsepower took higher-flowing heads, larger ports, a special cam with solid tappets, dual exhausts, dual four-barrel carburetors, and a mild 8.5:1 compression. With all that, it was reliable and easy to drive; 0-60 came in under ten seconds, excellent for the time if slow today. The car ran to 128 mph on the Daytona sand.

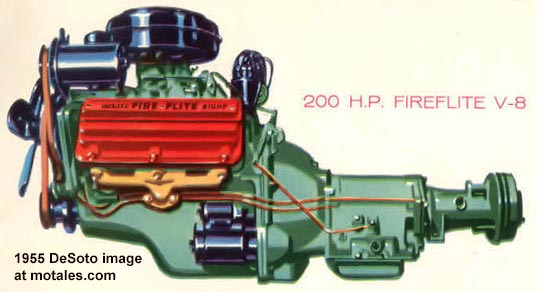

There were numerous changes to the various Hemis through the years, best shown in the table above. For example, in 1956, the 331 was bored out by 0.130 inches, moving up to 354 cubic inches (the same as the modern 5.7 Hemi), while altered heads raised compression to 9.0:1; the 300B reached 355 horsepower with another set of dealer-installed heads bringing compression to 10:1, the first time any production engine beat one horsepower per cubic inch. Meawhile, a 1955 DeSoto exclusive, the 291 powering all DeSotos from that year, produced 185 bhp with a two-barrel (on Firedome) and 200 bhp with a four-barrel, both from regular fuel.

The 300 series “letter cars” (C300, 300B, 300C, etc.) were a full package, with fine-for-the-time handling and braking to match the acceleration.

Chrysler created a racing test engine, K-310, to experiment with better exhaust headers; smoothed and expanded ports, and different carburetion and camshafts (with computers simulating different camshafts as well as physical trials). The K-310 ended up with 308 hp and 361 pound-feet, using stock pistons; adding 12.5:1 compression (requiring race gas) brought 353 horsepower and 385 pound-feet of torque. James Zeder wrote that the engine’s power was “comparable with Indianapolis engines, which have been developed for power without regard to any other purpose.”

An Indy engine, dubbed A311, used fuel injection, bigger valves and ports, racing manifolds, and a racing cam; it ran the same lap speeds as purpose-built racing motors. In June 1954, the top four Indy drivers brought their cars to run the new 4.7 mile long oval test track, which had wide lanes and banked curves that could handle 200mph speeds. The fastest lap was 179 mph; then the Hemi A311 test car ran a 182 mph lap. Hearing of this, the Indy officials ordered that only 272 cubic inch stock-based engines could run, and Chrysler dropped its attempt.

Meanwhile, Buck Baker won the NASCAR championship with a 1956 Chrysler 300B.

The DeSoto engine grew to 330 cubes with a raised block and larger bore, hitting 255 hp with an optional power setup; the Adventurer series, a late-1956 launch, had its own special engines as well, boring the 330 to 341 cubic inches and 320 horsepower (clearing the way for DeSoto to be the Indy 500 pace car). Dodge also had a raised-block version, moving to 315 cubic inches, and up to 260 horsepower with a factory upgrade; dealers could install twin four-barrels, but no power rating was revealed with that equipment. The cost was less than the Adventurer, though—while the hot Dodge D-500 trim dominated drag strips, the pecking order so far was clearly Chrysler first, then DeSoto, then Dodge. Plymouth was not yet on the V8 map.

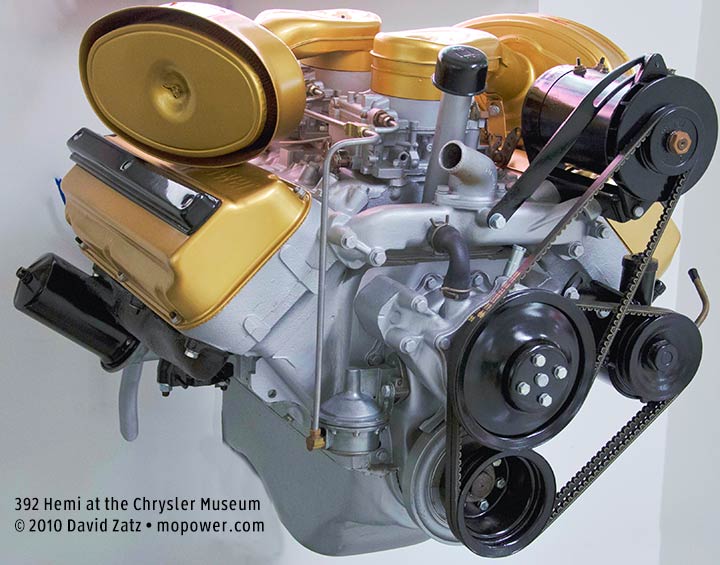

The biggest and boldest of the Hemis was the 392, created for 1957 with a 4-inch bore and 3.9 inch stroke—both greater than the prior biggest Hemi. This new FirePower was good for 325 horsepower, in standard form; in the 300C it went to 375, and with optional higher-compression heads, it reached 390 horses. 1957 was also the first year for the three-speed TorqueFlite automatic (replacing the two-speed), and something that would be on every Chrysler rear-drive car until the 21st century—a torsion bar front suspension.

The 392 300C was able to do 0-60 in 7.8 seconds (the same time recorded by the 1995 Neon, for perspective). The handling improved with the torsion bar front suspension, too. For 1957, DeSoto bored out its own dual rocker V8 to 345 cubic inches, hitting 345 horsepower with dual four-barrel carburetors. This was the first standard engine to reach one horsepower per cubic inch, and it was only slightly behind the 300C’s 392 in acceleration. Dodge grew the 315 to 325 horsepower and sold it in several forms, including one with a dealer-installed manifold and dual four-barrel setup.

The 1958 Chrysler 392 was similar to the 1957 model; it couldn’t be bored or stroked more, at least not without losing reliability. There was an electronic fuel injection setup created by Bendix, and rejected by the other automakers, with good reason: it wasn’t reliable over time, due to the sad shape of materials technology. Bosch would eventually buy the rights to it and dominate the fuel injection industry in the 1970s and 1980s with a modernized version—the basics were, though, present in 1957. It was rated at 390 horsepower but nearly all the systems were replaced by the 380 horsepower carburetor system.

Changes for 1958 included replacing the old crank with a forged steel unit, and cutting back on rear axle ratio variations, which had grown out of control. DeSoto dropped the Hemi for 1958, using new wedge engines; and Dodge kept only the 325, with 252 or 265 horsepower. It too mainly moved to new wedge-head engines. The only Hemi car for 1959 would be the Crown Imperial.

The first-generation dual rocker/Hemi had a good run, not just in cars; they were popular for air raid sirens, pumps, farm power systems, boats, and other industrial uses. Reliable and efficient, their main problems were size (they were quite wide), weight, cost, and manufacturing time; Chrysler couldn’t pump out a million dual-rocker V8s very quickly.

The engines were not dropped; they were refitted. While a truly brand new series of big-block wedge-head V8 engines were developed (the B series), the Hemis were stripped of their hemispherical heads and given polyspherical heads with simpler valve actuation—the “poly V8” series.

Trenton was not Chrysler’s only engine plant, but the explosion in V8 engines can be seen clearly in this graph. That would not have been practical with the Hemi design.

Once Chevy and Ford started selling V8s in large quantities, Chrysler needed an engine that could be made quickly, cheaply, and in huge numbers for Plymouth. They started from the Hemi V8 and worked it and worked it until they had something that was easily mass-produced, dubbed the A-engine. These were produced by Dodge for Plymouth for about a year while a new plant on Lynch Road was finished and tooled to supply Plymouth’s massive volume demands.

Not long afterwards, Engineering took one more step, making a lighter-weight block—the lightweight A—the LA series; a combination of lightweight casting and wedge heads made these engines smaller and much lighter. This is the engine that took some of the original Hemi and pushed it all the way into the modern era, with its basic design integrated into the 1990s’ Ram 1500 pickups and every Dodge Viper—but that’s another story.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos