The Chrysler Airflow was the first vehicle to be tested in a wind tunnel; but at Chrysler, it was also the last car to go into a wind tunnel for quite some time. Then, in 1968, Ford suddenly erased Chrysler’s NASCAR power advantage by running a car with better aerodynamics, one which had been created specifically for NASCAR.

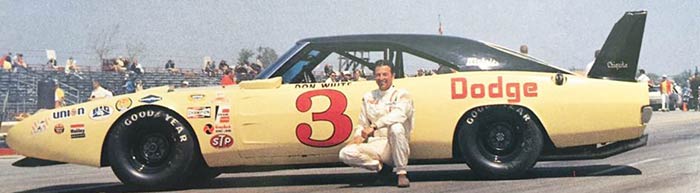

Dodge responded first, allegedly to win Richard Petty over from Plymouth, by issuing the Dodge Charger 500. This was an impressive effort, launched in early 1969, with far less drag than a normal-production Charger. To reduce wind resistance, engineers and technicians changed the rear wind glass and roof to make the roof-to-glass line flush, pulled the grille forward so that it was not recessed, and made other minor tweaks, all based on input from the race teams. Since NASCAR required actual stock versions of each car to be sold at that point, 500 were made for ordinary people to buy at Chrysler dealers.

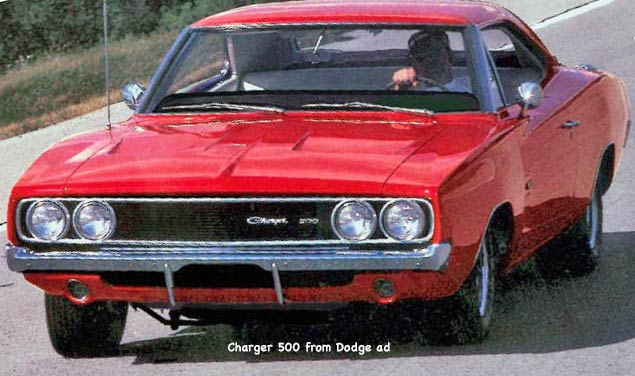

Compare the 1969 Charger 500 to the 1969 Charger R/T above

The Charger 500 worked fairly well, handing Dodge 15 wins, but in that same time, Ford’s custom-designed Talladega had 22 wins. Clearly something more was needed, and the people at Dodge were working on that even as the first 500s rolled out of the factory.

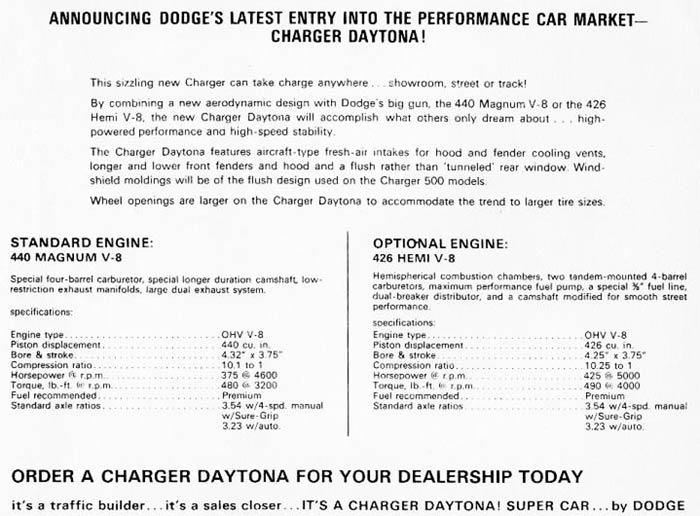

The Charger Daytona’s conceptual birth was reportedly when racing director Bob Rodger first saw the Ford Talladega, which, again, had been made specifically for NASCAR. Rodger told his boss, product planner Burt Bouwkamp, “NASCAR has gone ‘funny car’ racing,” and told Bouwkamp that they should built the ultimate racing car—as Burt Bouwkamp later wrote, “He said that we should design and build the ultimate race car and forget how practical it was or how it looked because we only had to build 500 of them to be approved by NASCAR as ‘stock.’ I got Corporate approval to do that and we developed and built 500 Charger Daytonas in 1969. Creative Industries built the cars for us.”

Bouwkamp had to get approval because of the money required for engineering and construction; as it was, the costs for tooling, engineering, and vendors “were more than the profit from the 2,000 winged warriors [including the Plymouth Superbird] that we eventually built and sold.” Just the variable (piece) costs were higher than the price paid by dealers. But, then, profit was never really the point—winning races was.

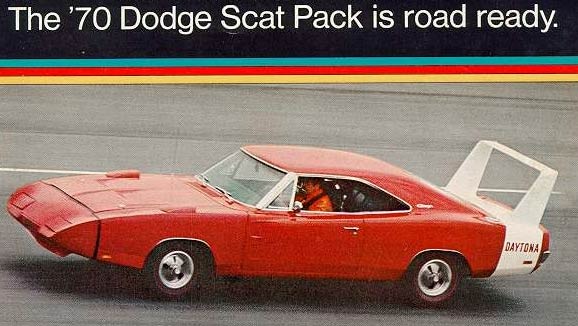

The coefficient of drag would have been even lower, but at high speeds, the rear tires started to lift; to keep traction at high speed, therefore, a massive spoiler, lifted far above the trunk, was added to keep the rear wheels firmly planted on the ground.

Dropping the coefficient of drag required more extreme steps than with the Charger 500, but it had to be something that fit within a reasonable budget; they couldn't redesign the sheet metal. The Daytona had to be built like an option package, starting with a production Dodge Charger; then the contractor, Creative Enterprises, took off unnecessary parts (such as the grille and bumper), and added on the custom gear. One of the two obvious additions was a “nose-cone” that deflected air away, giving the car a very late-1980s or early-1990s look (indeed, the front of the second-generation, front-drive Dodge Daytona looked fairly similar).

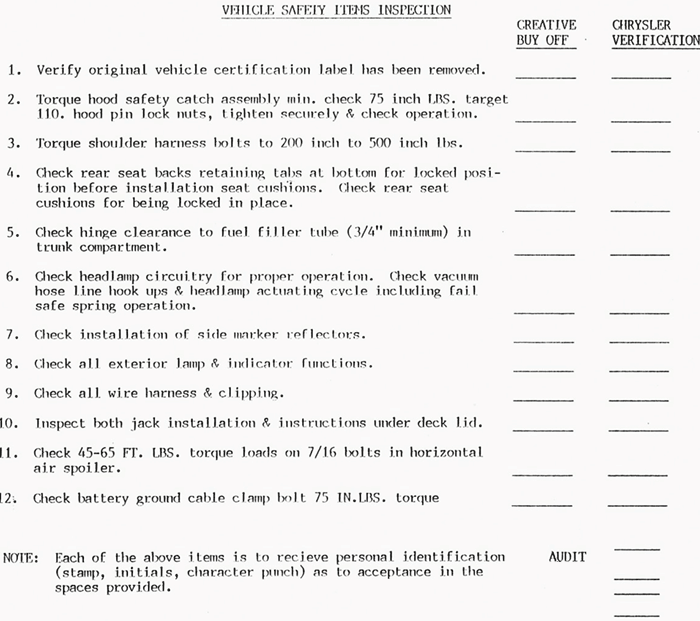

There was also the under-nose spoiler, vertical stabilizers, a backlight modification, tuned suspension parts, the big wing, and so on—but you can read the specific tasks here, all to be done by Creative Industries, for the production cars:

Most people know about the new nose and wing, of course, but not many realized that the car boasted 1970 fenders and hoods, even though the rest of the body was from the existing 1969 Chargers. Again, they had to be built with 1969 fenders and hoods, which were then removed and replaced. A Chrysler person had to check that each step was taken; both Creative and Chrysler had to verify a number of safety and regulatory issues were addressed, too:

Greg Kwiatkowski wrote that the 1969 Daytona racing car took the front lift of the Charger from 1,200 pounds to zero at racing speeds, due to a bigger front spoiler under the nose which added downforce to the front tires. The rear wing also added downforce and balacned the car, aerodynamically. A traditional rear spoiler would have caused far more drag, and the car would have lost top speed in straights and entered corners at lower speeds. NASCAR did solve the “problem” of the wing cars, in the end, by restricting cars to a three inch rear spoiler—just as they ended the use of Hemis by demanding unreasonable air restrictors.

There were two other stories explaining the tall rear spoiler, which appear to be apocryphal. One is that it’s three feet tall so the trunk can open; while an interview with an engineer at Chrysler, decades ago, included a comment to the effect that as the numbers kept getting better as they raised the spoiler until it was three feet off the car, that’s where they left it. (The latter could actually be true, but the former probably is not—though being able to open the trunk is handy on a production car.)

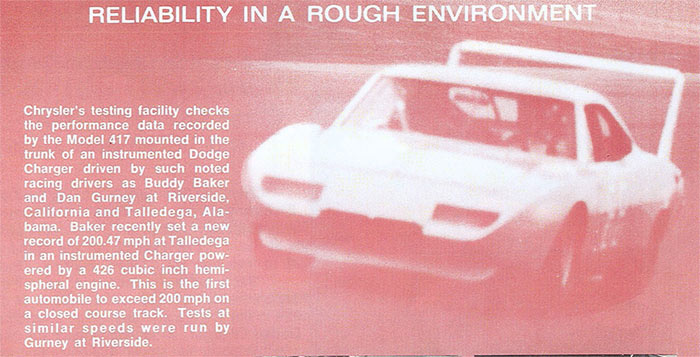

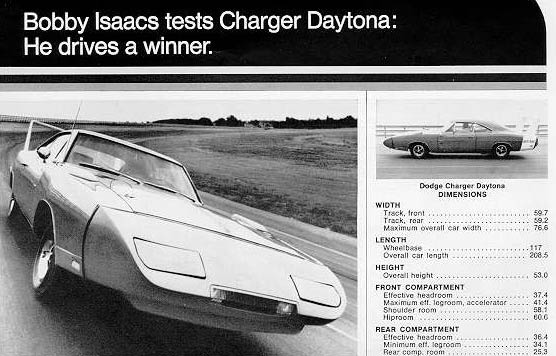

Thanks to these modifications and its optional 426 Hemi engine (a high-performance 440 was standard), the Charger Daytona easily ran speeds that ordinary NASCAR cars could only dream of—even the Talladega—and 180 mph was within reach of amateur drivers, given enough empty road, good luck, and skilled tuning. On a professionally tweaked car, Buddy Baker still set a 200.447 mph record on March 24, 1970 at Talladega. That speed record stood for 13 years, to be broken by about 1 mph in 1983. More to the point, from the September 1969 debut of the Charger Daytona, Dodge won 45 out of the next 59 races.

There were problems with the car; handling could be tricky, and forward visibility was a bit difficult to judge. The downforce burned up tires quickly, especially on some tracks which had a grippier surface. Chrysler ended up racing different cars on shorter tracks, where the top speed down the straights was less important. Driven too slowly, more likely an issue for the civilian version, the Charger Daytona could overheat, too—thanks to the loss of its traditional grille. The Plymouth Superbird avoided this problem.

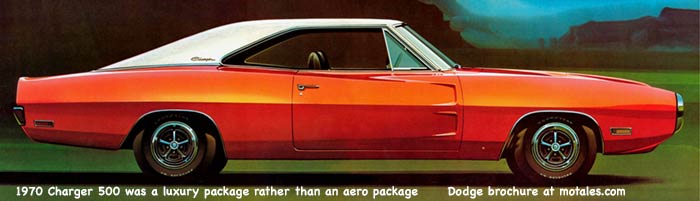

What of the Charger 500, you may ask? The 1969 Charger 500 was produced solely for the aero treatment; once the Charger Daytona was out, there was no need for the less aerodynamic 500. Thus, the 1970 Charger 500, shown above, was pitched as a luxury package, and did not have the flush windows or special grille of the 1969s.

GM connection. Russ Shreve wrote that, in 1965, he hired with Jim Amick, an aerodynamics expert with the University of Michigan, in the university wind tunnel to test aero features for a J.C. Penney-sponsored international sports racing car. Amick proposed a large wing—or, as he called it, a horizontal airfoil, around 20 inches above the rear deck, spanning the width of the car. Shreve’s partner took a copy of the report to car builder and driver Jim Hall after Penny dropped their plans. Shreve said that, in 1972, Larry Shinoda (who was involved with Jim Hall) confirmed that the report had been given to them, and that they then tried it out.

Without the kind of tuning and tweaking used on Buddy Baker’s car, the stock Hemi-powered Charger Daytona’s top speed was around 180 mph; the price was around $4,000.

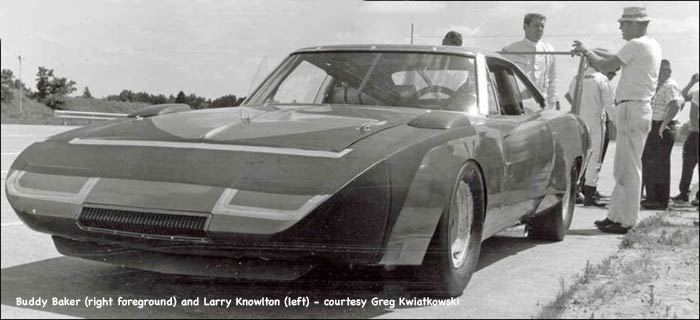

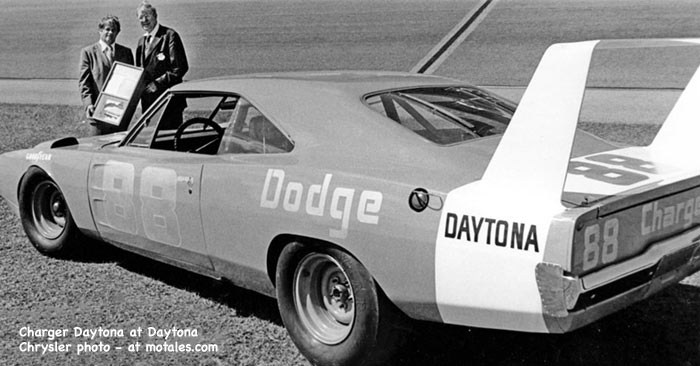

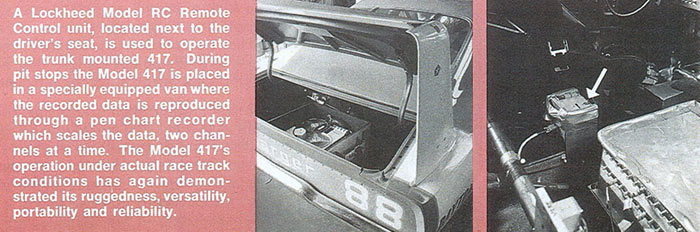

Car DC-93 (which later became #88) was tested at Huntsville’s airport for drag; they ran it to high speed and then coasted in neutral to see the effects of various changes on drag, without needing a wind tunnel—just time. That provided a rough measure of drag and included the impact of the road surface passing by, something wind tunnels of the day did not take into account. Greg Kwiatkowski, who recounted this tale, also pointed out that in the #88 car, the front “nose cone” lower valance was sealed back to the engine cross member; Greg said that Larry Rathgeb thought it was important to the design that it be sealed that way, but many of the cars they raced were not done the same way.

A good deal of testing used Chrysler’s Huntsville electronics experts, who would go on to work on the Mopar Missile series of drag cars. They pioneered digital testing of cars for aerodynamics, fuel delivery, crash safety, and other key areas, in some cases using computers carried in vans and connected by cables.

Chrysler dominated NASCAR for 18 months, winning 75% of races (including every long track race). Plymouth wanted to attract Richard Petty back, and to do so, they developed a similar car—the Plymouth Superbird, made in 1970. This is another story, but NASCAR had upped its sales requirements, and they had to make 1,500 retail versions of this car.

Since tripling the production requirements didn’t kill off the made-for-the-track cars, NASCAR restricted aero cars to a 300 cubic inch engine for the 1971 racing season, killing their ability to win, and later limited spoilers to three inches. The Charger Daytona, needless to say, did not return to dealer lots.

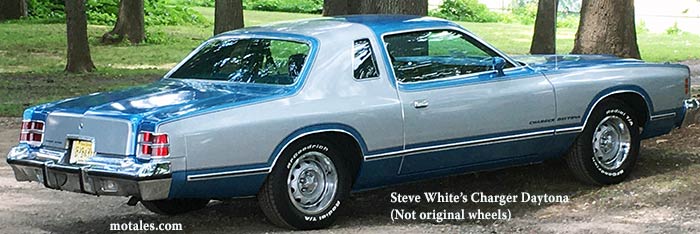

The name was revived for the 1975 Charger Daytona (shown above), but that was a “personal luxury car”—a twin of the Cordoba with only small changes to mark it as a Dodge. The name was brought back again for the 2006 Dodge Charger, but there was no aero package and no special engine. Oddly, again, the front wheel drive Dodge (not Charger) Daytona bore the strongest physical resemblance to the race-bred 1969-1970 cars.

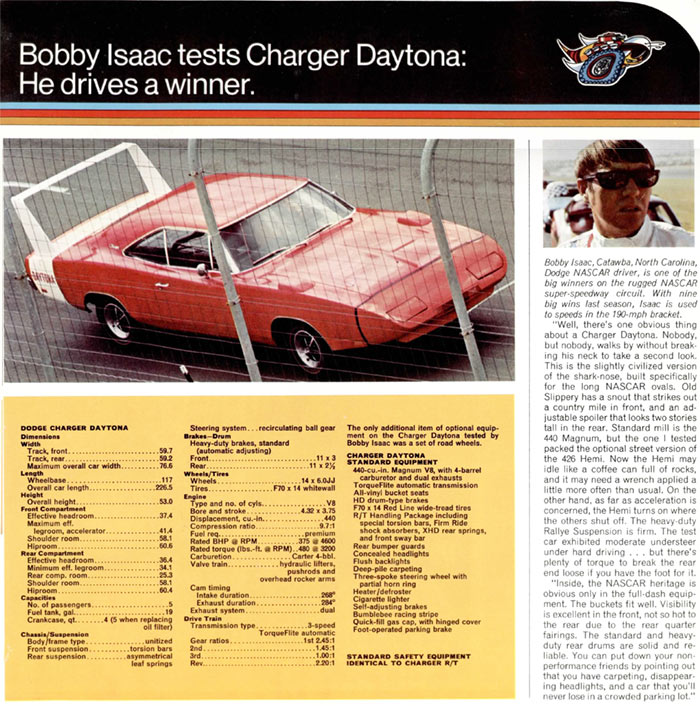

The retail version of the Dodge Charger Daytona came with self-adjusting heavy duty brakes, a customized heavy duty suspension, rear bumper guards, vinyl-covered bucket seats, carpeting, and a quick-fill gas cap, along with the other Charger amenities.

The car was 5.7 meters, or nearly 19 feet, long. The 14x6.0JJ tires translate roughly to P195R14s, which seems rather small for the power; but the downforce likely compensated for that, at least at high speeds. The fuel tank held a hefty 19 gallons of premium.

Base powertrain: 7.2 liters, Carter AVS carburetor.

Optional 426 Hemi: Carter AFB 4V carburetor, 425 horsepower (gross).

Key links: Winged Warriors club

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky