The 1968 Plymouth Road Runner was an ideal Plymouth muscle car, providing an exceptional value for those who wanted high power, decent handling, and good braking—and who didn’t care whether the floors were carpeted. It was essentially a hopped-up Belvedere two-door with upgraded brake and suspension parts.

When Ford made more aerodynamic cars for NASCAR racing, Dodge leapfrogged them with the Charger 500, which had a flush rear window, redone nose, and other aero touches. Dodge jumped in with both feet with the 1969 Charger Daytona, whose big wing aided stability and braking; its grille was covered by a big nose. Despite the massive rear spoiler, it managed to have a drag coefficient of just 0.28, similar to the later Dodge Neon.

To lure Richard Petty back from Dodge, Plymouth needed more than their Road Runner could give; its styling made it even harder to fix aero issues than the Charger had been. Plymouth ended up taking the Charger Daytona idea for itself, creating the Road Runner Superbird. There was much more to this car than just giving a racing helmet to the Road Runner and shoving a cone over the headlights.

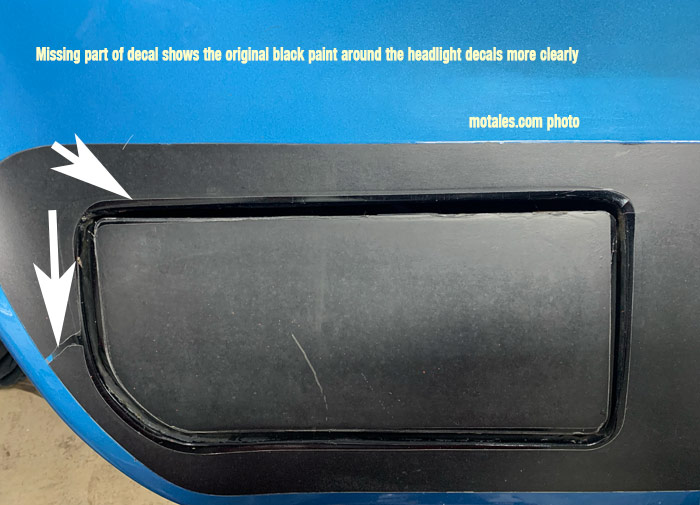

Starting at the front of the car, we have the big nose designed to split the air. The nose is far from empty, holding mechanisms for the pop-up headlights, air directors, wiring for the headlights, and such. The black area around the headlights is not just a big black decal (which must have been a bear for the factory to install); to avoid having the factory paint show up around the headlights, they painted an area of glossy black paint around the headlights. The border would be covered up by the black decal. Some restorations don’t have the black paint, so the body color paint shows as a border around the headlight opening.

The nose looks like it could be fiberglass, and maybe that would have made sense, but it’s actually steel. That means making new ones would be prohitively expensive. The spacer between the nose and the car’s normal radiator mount is also steel. Incidentally, the Superbird was reportedly a bit less aerodynamic than the Charger Daytona—Plymouth did not have a car like the Charger to start with!—and there were some reports at the time that it could overheat and lower speeds despite the shrouded fan and the largest company radiator that would fit.

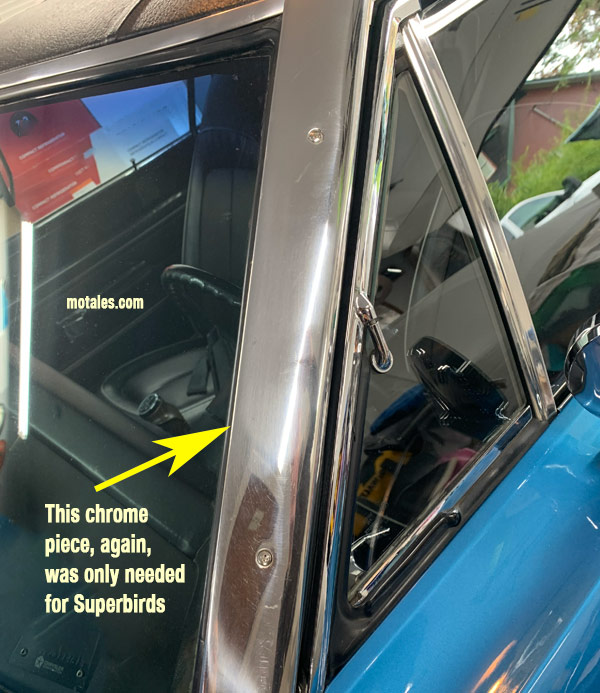

The pillars are covered with chrome fittings to reduce air resistance. The roof of every Superbird is vinyl, to hide alterations to the metalwork.

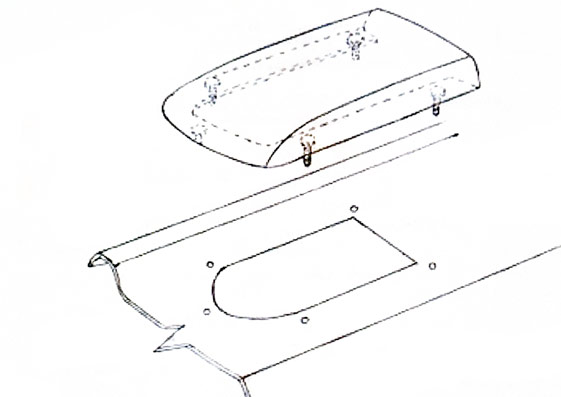

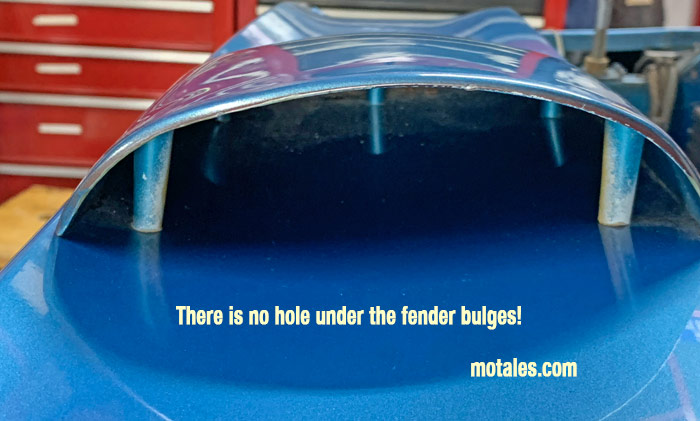

The fender bulges seem like they were meant to cover holes for ventilating the brakes or giving extra wheel clearance; and maybe they did on the NASCAR racers, but on the actual production cars, they just sat over solid metal. The purpose may have been aerodynamic rather than decorative. As with other parts of this car, they are held on quite firmly; they were made by injection molding and, unlike the nose are not made of steel.

After the Superbird was released, Chrysler issued a service bulletin (#70-23-6) authorizing dealers to make holes for customers who insisted on them! The introduction to this bulletin read, “The designed and released front fender opening, under the air scoop, was not incorporated in production due to the necessary major die modifications.” It instructed dealers to remove the air scoop retaining nuts, take off the scoop, scribe a line around 3/8” inside the front fender air scoop bolt circle, cut on the line, and reinstall the air scoop. One can imagine that a careless or sloppy dealer might leave a serious opportunity for rust, especially since they didn’t instruct dealers to prime or paint the metal exposed by this!

The hole really was needed because the NASCAR cars had them. (This information was provided by PettyMower on the DodgeCharger.com forum).

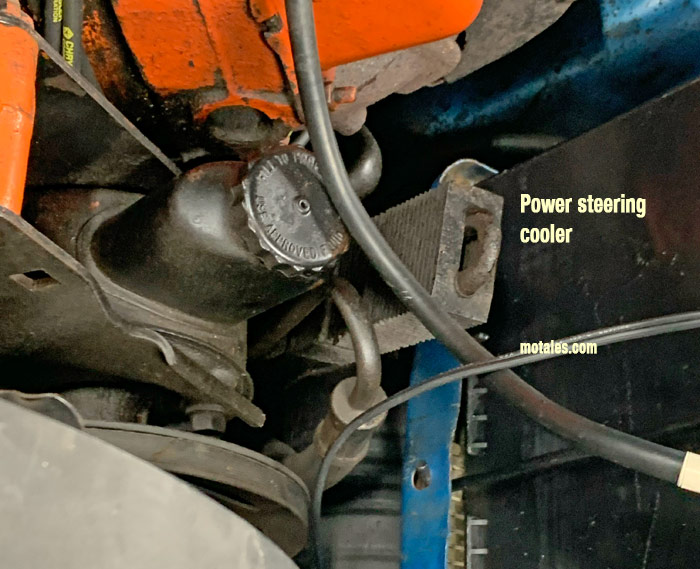

Almost hidden under the hood is a special cooler for the power steering motor.

Alterations to the rear window and trunk opening were difficult to cover up; one solution was these odd diamond-shaped pieces, used on Superbirds but not Road Runners.

Making the rear window flush was quite hard, given the original body designs, which were not as dimensionally perfect as they could be anyway—keeping in mind the Road Runner was a modified Belvedere, cars meant to be built to a budget in the hundreds of thousands. The contours of the rear windows were somewhat different, and you can see gaps between the metal and the window in this particular Superbird. These are not the standard openings.

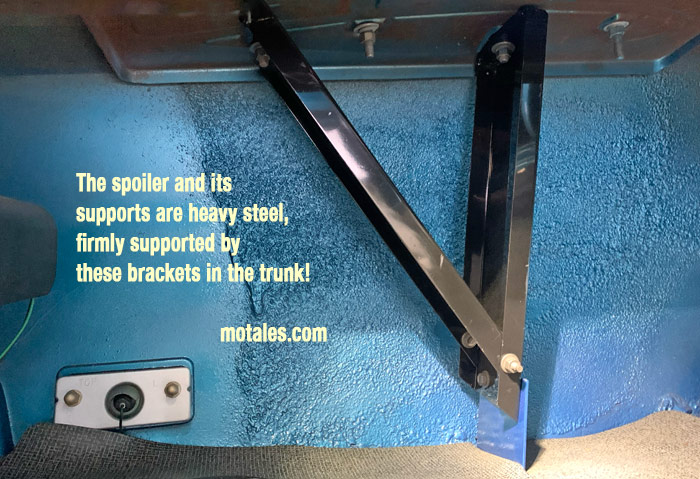

Those massive wings were made of extruded aluminum (we’ll fix the caption), and they were built tough enough that people could sit on top of them. To support all that weight, the engineers put supports into the trunk; otherwise, sitting on the fender could dent it. Indeed, the pressure of the spoiler’s downforce could easily push the fender in! The supports would be needed at high speed even without any added weight. These were not just meant to avoid downward pressure, but upward pressure.

The tilt of the wing top can be adjusted by loosening the Allen bolts on the sides, an unusual feature for a production car.

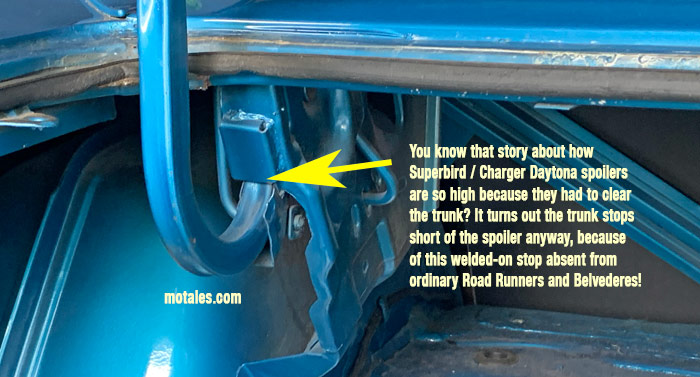

One story about the Charger Daytona and Superbird is that they raised the wing to allow the trunk lid to clear it; but this doesn’t seem to be true, since the Superbird clearly has stops that prevent the trunk from reaching the spoiler. These stops, welded firmly into place on the stock hinges, saved some tooling costs and easily prevent the trunk lid from reaching the spoiler. Whether the trunk lid could open further is a mystery.

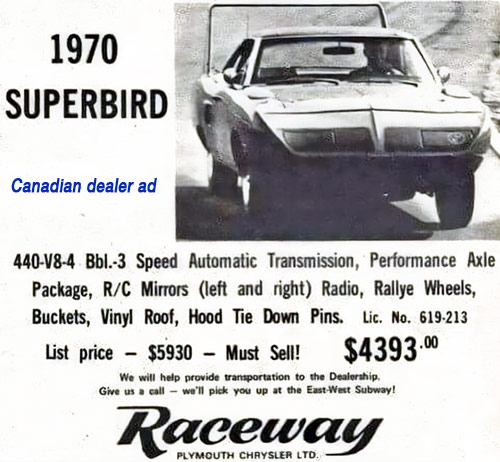

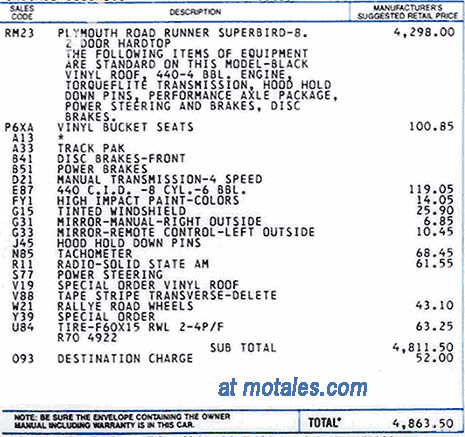

Plymouth made fewer than 2,000 Superbirds, all of them to meet NASCAR requirements for stock cars rather than to make a profit. NASCAR didn’t take their word for it, but surveyed dealerships to confirm that the cars were actually being made and sold. The company had thousands of dealerships so most likely this was done via spot checks. The passenger-side mirror, incidentally, was not standard despite the high price of the car; it was optional. Even with the list price as high as it was, Plymouth likely took a bath on each car they sold to the general public, all in the name of “win on Sunday, sell on Monday.”

The strategy worked for a while, though few customers liked the then-radical looks of the cars or their greater length; but NASCAR rule changes ended the reign of the “wing cars.” For many years they were unwanted by retail buyers, and some were reportedly converted back to Road Runners by dealers to clear them off the lots. Wing cars were still relatively cheap in the 1980s, but today their rarity, heritage, and characteristics make them quite valuable.

Greg Kwiatkowski, who owns the famed 200-mph Charger Daytona, pointed out that the cone was painted in lacquer, while the body was done in enamel; the colors fade differently over time.

The state of Maryland banned the 1970 Plymouth Superbird from its roads in April 1970, because they didn’t have a front bumper, as required by state law. While Chrysler claimed to have researched the laws in every state, they missed Maryland. Owners were supposed to contact dealers and arrange to have bumper installed. In the meantime, unsold cars could not be titled in Maryland; and they were supposed to be kept out of Maryland highways. No other state banned the car.

Based on Vincent Plotino’s experience and research, manufacturer brochures and advertisements, The Standard Catalog of Chrysler, the Plymouth Bulletin, and Allpar.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky