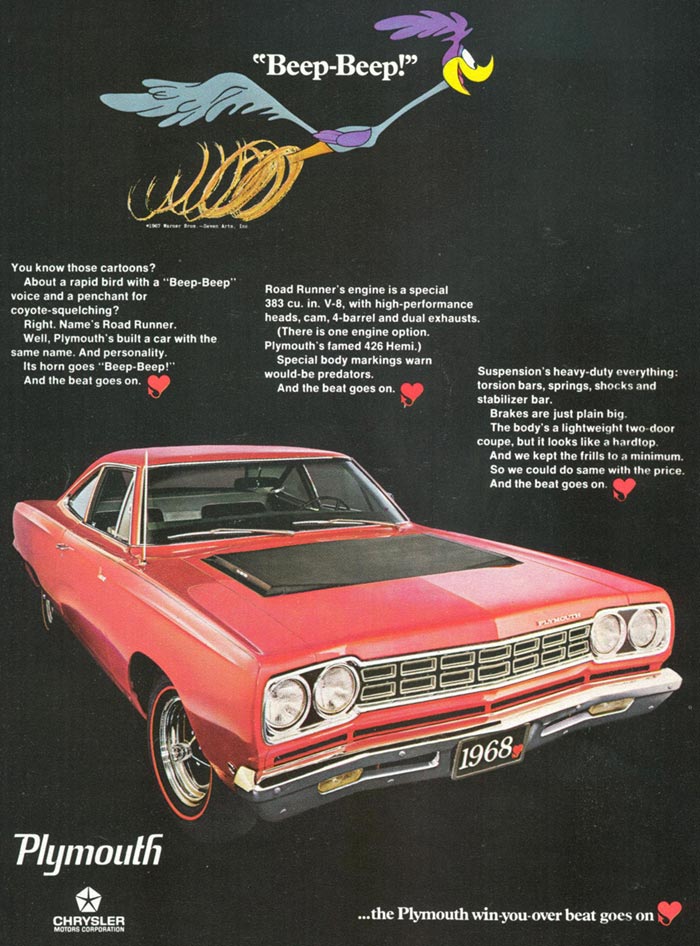

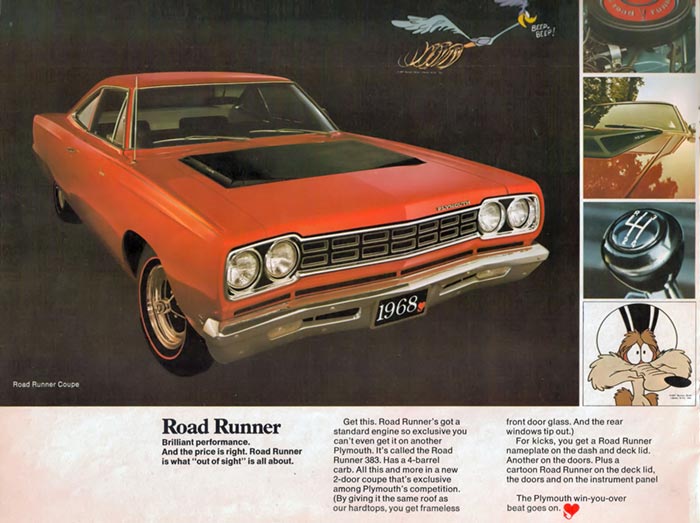

The 1968 Plymouth Road Runner was the perfect Plymouth muscle car—made on a budget and to a budget, but providing an exceptional value for those who wanted high power, reasonably good handling, and braking—and didn’t care whether the floors were carpeted.

The story starts with John “Jack” L. Smith. At Studebaker, he ran the Mobilgas Economy Runs; he joined Chrysler in 1957 and rose through product planning, retiring in 1980 as chief engineer of vehicle emissions and fuel economy planning (in 1972, just a few years after the Road Runner, he evaluated (with humor and accuracy) Wankel engines).

The idea for the Pontiac GTO came from either Jim Wangers, an ad man for the Pontiac LeMans, or John DeLorean; either way, they saw younger buyers modifying their cars and thought of making a performance car from the mid-size class, rather than from the usual full-size range (e.g. Chrysler 300, Dodge D-500, Plymouth Fury). That led to the 1964 Pontiac GTO—and other affording performance models, such as the Cutlass 442.

In 1965, Dodge and Plymouth created dedicated planning groups for their midsize cars, putting Jack Smith in charge of the Plymouth group—and charging him with making a GTO competitor. That became the Plymouth GTX, the highest-trim Belvedere with their biggest engine, a strong but expensive car. Plymouth was seen as too conservative for younger buyers to take the bait; only 12,000 GTX cars sold in 1967, versus 81,000 GTOs (not to mention the Chevy SS and Olds 442).

Chrysler-Plymouth sales chief Bob Anderson reportedly asked writer Brock Yates how to get kids’ attention; Yates told him to strip out every nonessential item from an existing car and put in the biggest engine they had. Nobody had done this kind of bare-bones performance car before, though some at Chrysler had thought about it. Smith’s own car was a low-end Belvedere II with a 383 four-barrel engine, four-on-the-floor transmission, police brakes, and heavy duty suspension. The idea was sound, so they adopted some objective standards for a barebones performance car—all applying the car “as sold,” or, in other words, “bone stock.”

The mechanical parts of the car were already at hand, because Fleet Engineering, under Dave Hubbs, had developed them for police cars, which were strong enough for Chrysler to take 51% of the police-car market (civilian buyers could specify the same options, most of the time). To save money, they used the basic Belvedere gauges and dashboard.

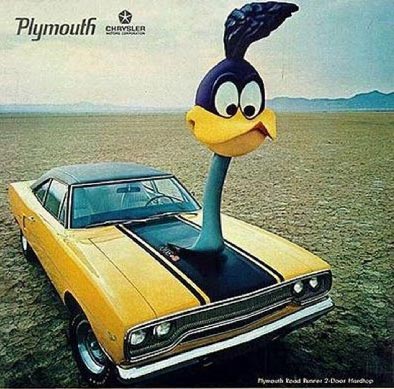

The hard part was getting credibility among younger buyers, including a suitable name, a task Anderson left to Plymouth’s ad agency. Then, though, Gordon Cherry found the perfect name. He asked Smith to watch Saturday morning cartoons: “There’s this bird, he has all the characteristics of our car. I want you to watch television and tell me what you think.”

The bird was the Road Runner, who can’t be caught by the coyote because he’s agile, “a happy-go-lucky guy, loping along...a happy personality. He can take off the line very quickly!” He could stop very quickly, too.

To appeal to youth, Smith felt, you had to leave “the next older generation feeling a little awkward. Not that you want to alienate them, but just have them feel a little awkward.... The idea of putting a bird on a car, and maybe going so low as to make the horn go ‘Meep, meep!’ was exactly the kind of thing that would say, ‘This is a young person’s car!’ It wouldn’t necessarily make the older people mad; they’d just sort of maybe give it a few whimsical snickers.”

Young & Rubicam weighed in with their choice: LaMancha, because Man of La Mancha was a hit musical, and maybe because it sounded a bit like (Pontiac) LeMans. Smith put them through the process Gordon Cherry had used: he asking if the advertising men watched cartoons on television. They did. He suggested the name, and, in his words:

There was absolute silence at the table.... The young man from the art department was at the other end of the table with his head in his arms. He was thinking. ... and his body began to convulsively shake. He got our attention for fifteen to twenty seconds—that’s a long time for a table to be quiet... Suddenly his hands came down and he sat up and he said, “God! I could really do a lot with that!”

He broke the spell, God bless him. And God bless Young & Rubicam because they recognized the possibilities. Within a minute of quick conversation, they had torn up their list and said, without research, “Road Runner is the name we’re going to suggest.”

Smith had to negotiate with Warner Brothers. Warner Brothers pointed out that they had a valuable property they could sell to anyone else; Plymouth pointed out that “Road Runner” was copyrighted but “roadrunner,” the real bird, was not. To keep control (and the money), Warner Brothers had to give in; they agreed to the use of the name and art for $50,000 per year.

Cartoonist Chuck Jones (who was alive and well through the Road Runner’s life as a car) had gotten the idea for the meep-meep when a cartoonist was trying to get through the hallway with his arms full of drawings, going “beep beep! beep beep!” to avoid bumping into people. Now, Smith, armed with a tape of a man repeatedly saying “meep, meep!” went to Chrysler’s horn providers. Two said no; the third said they had one that was close, but would cost a stunning $45 each, because it was designed for the military and could work under water. Smith asked them to strip off everything they could and keep it legal, and the company was able to bid just 47¢ above the usual price—a huge premium, but worth it.

Smith demanded a unique air cleaner cover and a unique engine. Dick Maxwell, one of the racing people, suggested using the hot 440 cam from the GTX in the 383 four-barrel. It was, though, a big “ask” of Manufacturing, since they would then have to keep two more engine assemblies in stock at the plants—one for automatics, one for manuals. The chief engineer for Car and Truck Assembly, Bob Steere, listened to Smith’s story of the youth market and why he needed the car, not saying a word; then said, “Go do it!”

Dean Engle, chief engineer of Powerplant Engineering, thought the cam timing wouldn’t work; so they built a test car, and, indeed, it didn’t seem right. Frank Anderzjak at the Product Planning garage immediately realized it had the wrong axle ratio, so they switched axles, and it still didn’t work out. This time, Frank pointed to the torque converter; not only did that fix the feel, but two years later, Dean had all the 383s using the same combination.

With all these obstacles cleared, a new one showed up: Chrysler-Plymouth styling director Dick Macadam. He, Bob Anderson (head of Chrysler-Plymouth sales), and Jack Smith met in the hallway one day, and Macadam pointed his finger and Anderson, saying “Nobody, but nobody, will ever put a cartoon bird on one of my cars!”

Anderson gave in, but Smith, seeing the project slipping away, interjected: “Look, we’ve done enough research to think this is a great idea. We think the kids are gonna love it. At least, let’s get this decal going, and we can put it in the glove box with instructions, and we’ll let the owner decide whether he wants it on his car or not. Now, how can you say ‘No’ to the owner?”

They agreed, but Macadam reserved the right to pick the bird from the pile of drawings. He chose one that was walking, not running, and in black and white; and it was never used in the advertising. The decal was left in the glove box, for the moment.

Virgil Boyd, president of Chrysler, had a dealer council meeting shortly after; he took the dealer representatives through the 1968 cars, including the decal-less Road Runner. Smith asked an employee, Bruce Scott, to take four photos of the decals, cut them out carefully so they looked like decals, and glue them to the cars ready for viewing.”

One owner had a dealership in New Mexico, where the roadrunner (lower case) is the state bird, which helped; but, in any case, the dealers were happy with all the cars. Smith walked up to Bob Anderson as the meeting broke up, and asked if he noticed the bird was on the car. Then he said: “I’ll tell you what: let’s make a decision, and put it on the car in the factories, if they’ll do it.”

“Okay.”

The car itself, Smith pointed out, looked kind of plain, though it had clean, organic lines; but so much was shared with the Belvedere that it would be a hard sell.

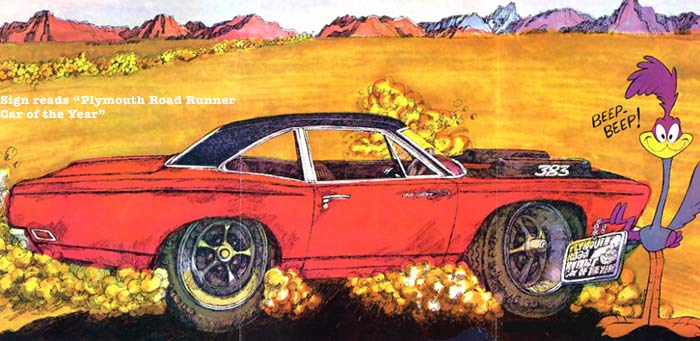

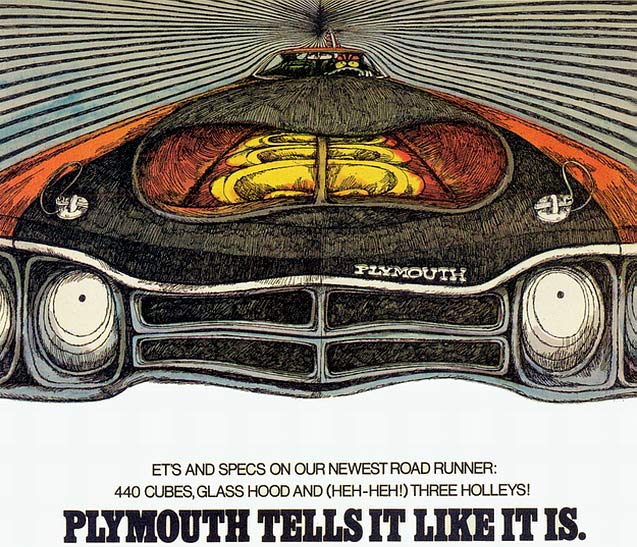

We start with the bird. There he goes, beating a cloud of dust. Now what if we took his feet and added a wheel? Then he is on wheels and the dust becomes burning rubber and we tum it into a car. There’s the car. Now that’s Road Runner in every respect except it’s exaggerated a little bit. Needless to say the tires are bigger. The scoops on the hood are bigger. See the two-page ad that appeared in November of 1967 in the hard core muscle car magazines such as Hot Rod, Car Craft and Popular Hotrodding. ... We don’t have to read the ad to know what it should say about performance and the four-on-the-floor as standard equipment, brakes, engine and all that stuff.

... These ads did a really good job, and after a while we expanded it beyond the Road Runner. Here is a GTX ad in which we used the same technique on that car. you'll recognize the car except, of course, the wheels are overemphasized as it is driving off in a cloud of burning rubber.

Smith told Purchasing to expect to sell another 2,000 midsize Plymouths, solely because of the Road Runner. It was a smash hit, though, and they couldn’t keep the dealerships stocked. They sold 45,000 Road Runners in 1968; Smith thought they could have sold double that number if they had the stock. Plymouth’s two mid-sized muscle cars, including Road Runner, hit just 63,000 sales. Now, they had problems getting parts and production. In a year when industry sales rose by 3.5%, Plymouth rose by 18%; Plymouth was no longer a no-contact zone for younger buyers.

I'm not saying it was all Road Runner, but Road Runner had made the showroom a swinging, desirable and interesting place to be. Now when a kid would say, “Daddy, buy a Road Runner when you get that new car,” the guy may say, ’’I'm not going to buy a Road Runner, son, but I’ll at least buy a Plymouth.”

That’s how it would work. So, what was the Road Runner responsible for in overall profit? I don’t know. One time I made a few estimates, and I figured it might have been $100 million, which is a hell of a return on a tooling investment that was under $500.

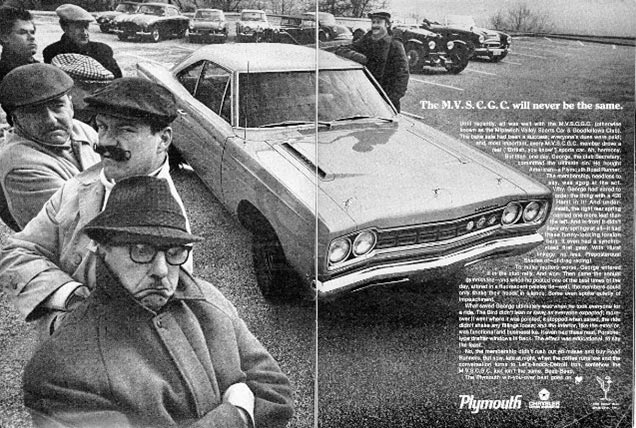

The car was selling, and some of the sales were to older people, so they began advertising for that generation. Reflecting that reality is an ad created featuring the fictional Mipswich Valley Sports Car and Goodfellows Club with their cars in the back—all British cars. The written material tells the story of the club and how their secretary had been so audacious as to go out and buy a Road Runner with a Hemi engine, he was almost thrown out of the club but he entered the car in the club’s competitions and won; [he] took them for rides and they thought, “Boy, it goes where it’s pointed, and it handles pretty well, and it’s a thoroughly desirable car... The Bird didn’t lean or sway as everyone expected; moreover it went where it was pointed, it stopped when asked, the ride didn’t shake any fillings loose; and the interior, like the exterior, was functional and businesslike. ...”

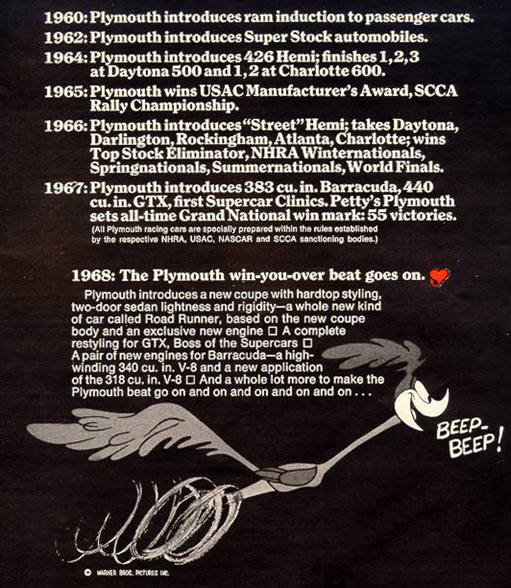

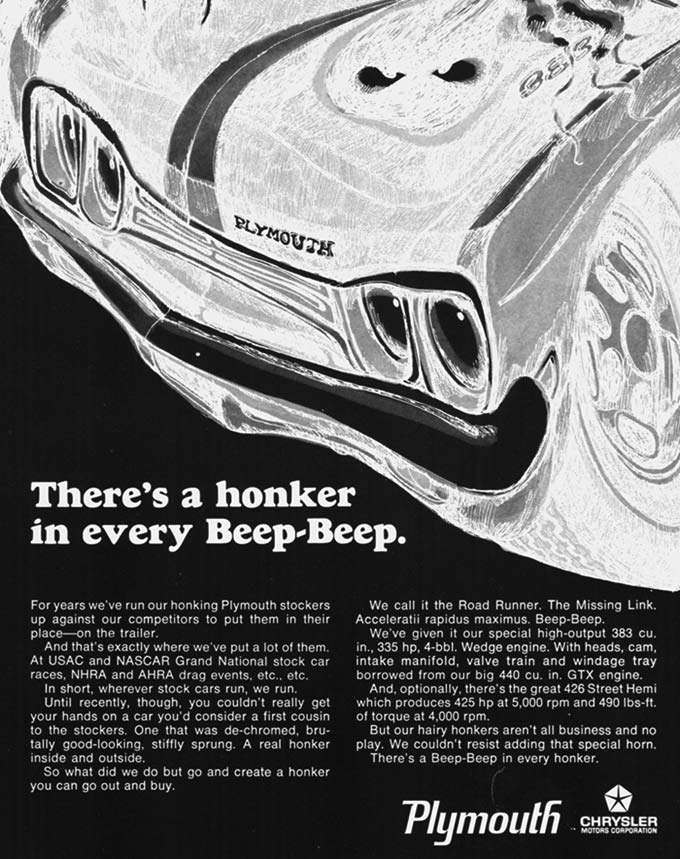

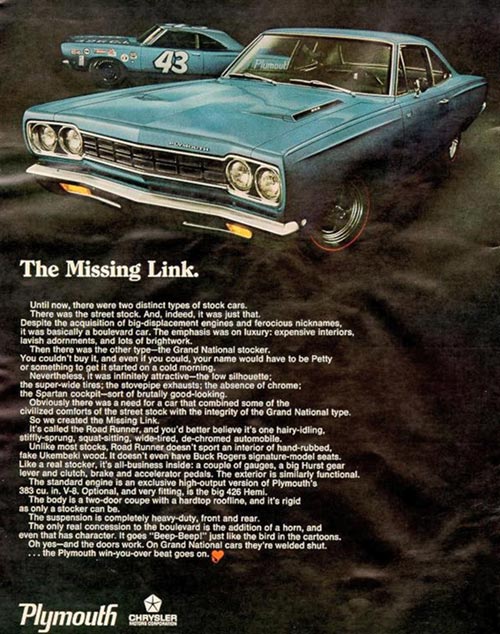

Another ad compared the Road Runner with cars like the GTO and GTX, expensive and highly trimmed, and actual NASCAR racing cars. (We typed out the text for you, since it’s small in our image.)

Until now, there were two distinct type of stock cars. There was street stock. And, indeed, it was just that. Despite the acquisition of big-displacement engines and ferocious nicknames, it was basically just a boulevard car. The emphasis was on luxury: expensive interiors, lavish adornments, and lots of brightwork.

Then there was the other type — the Grand National stocker. You couldn’t buy it, and even if you could, your name would have to be Petty or something to get it started on a cold morning. Nevertheless, it was infinitely attractive — the low silhouette; the super-wide tires; the stovepipe exhausts; the absence of chrome; the Spartan cockpit — sort of brutally good-looking.

Obviously there was a need for a car that combined some of the creature comforts of the street stock with the integrity of the Grand National type. So we created the Missing Link. It’s called the Road Runner, and you’d better believe it’s one hairy-idling, stiffly-sprung, squat-sitting, wide-tired, de-chromed automobile.

... Like a real stocker, it’s all business inside: a couple of gauges, a bit Hurst gear lever and clutch, brake and accelerator pedals. The exterior is similarly functional.

The standard engine is an exclusive high-output version of Plymouth’s 383 cubic inch V8. Optional, and very fitting, is the big 426 Hemi.

The body is a two-door coupe with a hardtop roofline, and it’s rigid as only a stocker can be. The suspension is completely heavy-duty, front and rear. The only real concession to the boulevard is the addition of a horn, and even that has character, it goes “beep-beep!” just like the bird in the cartoons.

Oh, yes—and the doors work. On Grand National cars they’re welded shut.

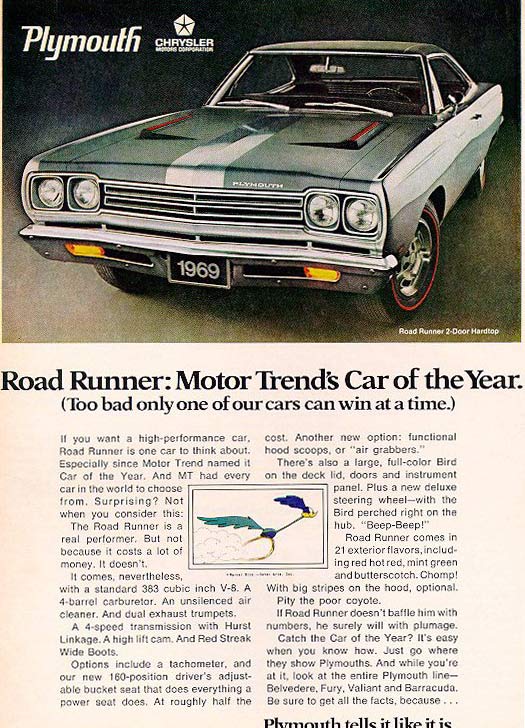

The success allowed the 1969 Road Runners to have a purple-painted horn with a decal reading “Voice of the Road Runner.” The stick-shift was upgraded to a Hurst model, and the decals became color, wtih a running bird; and a hardtop and convertible were added to the coupe (a hardtop has no pillar between front and rear windows). It even became Motor Trend Car of the Year.

The 1968 Plymouth Roadrunner was a first in American automotive history: a high-power, but budget-priced muscle car, based on the mid-sized (“B-body”) Belvedere. Twin goals were cutting weight and cutting cost, so non-performance amenities like carpet were dropped. One area where Plymouth beat GTO with certainty was in brakes—the Road Runner had heavy duty suspensions and brakes, and the Hemi option beefed up both of them.

Reportedly a favorite of moonshiners, the Road Runner’s lack of luxury trim and its special cam made it faster than most police cars; and its use of police parts made it tough and able to easily deal with potholes and bumps.

The 1968 Road Runner’s 383 V8 used the cam, heads, and intake and exhaust manifolds from the 440 Super Commando; the combination was rated at 335 gross horsepower, a new peak for the 383 (torque was 425 pound-feet, well below the old dual-carburetor ram-air setup but still quite respectable). The four-speed manual transmission was standard, the three-speed TorqueFlite optional. The only optional engine (for now) was the 426 Hemi V8, adding $714 in 1968 but turning the Road Runner into the ultimate road racer.

1968 Road Runner sales ended up at 44,599, more than doubling the GTX, and easily beating the Barracuda—and the Belvedere itself. Burt Bouwkamp wrote that some of that success was due to being the first performance car to be based on the lowest-price midsized car they had. It helped that the Road Runner, though larger than the GTO (and LeMans), was considerably cheaper, lighter, and larger inside. The GTO had a variety of tunes for its 400 V8, starting with the two-barrel (265 hp) and rapidly moving up; the 383 had only a bit less power than the top GTO engine, but buyers could always end the argument with the 426 Hemi. Pontiac, seeing this, launched a “decontented” version of the GTO, which kept the performance goods but lost unnecessary trim—the 1969 GTO Judge.

Given Plymouth’s success, Dodge decided to semi-abandon its senior status and created the 1969 Dodge Super Bee; as befit the higher-cost Dodge, the latter had 3D die-cast medallions rather than decals. Dodge’s base car, the Coronet, had a longer wheelbase than the Belvedere, so the Super Bee ended up being 65 pounds heavier than the Road Runner. It did have a nicer gauge cluster (from the Dodge Charger) and a Hurst Competition Plus shifter and linkage—much better than the Road Runner’s Inland shifter; Plymouth followed and moved to Hurst.

One of the more fun 1969 additions was a cold air induction system, Air Grabber; from the cabin, owners could press a button to make a vacuum-controlled hood scoop pop up or back down to hood level. Dodge Super Bees had it, too, but the Plymouth had neat “Coyote Duster” graphics.

| 383 | 440 | 426 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression | 9.5:1 | 10.5:1 | 10.25:1 |

| Air cleaner | dual snorkel | unsilenced | unsilenced |

| Horsepower (gross) |

335 @ 5200 | 390 @ 4700 | 425 @ 5000 |

| Torque (pound-feet) |

425 @ 3400 | 490 @ 3200 | 490 @ 4000 |

More prosaic changes included the new clean air system, which included changes in choke modulation, higher-rated thermostats (190°F), a 50-rpm higher idle speed, and removal of the CAP-valve-controlled spark timing system (kept on the Hemi) and the altered spark curves it brought. Drum breaks got a better self-adjustment feature and redesigned drums with radial fins. The Hurst shifter used on Dodge Super Bees was optional, along with Sure-Grip locking differentials.

The 1969 Road Runner won Motor Trend’s Car of the Year award, despite the new Ford Cobra, which was based on a Fairlane but carried a 428. For this year, the Road Runner finally gained a 440—with triple two-barrel carburetors. It still had no 440 four-barrel, though that was a popular swap—and sometimes buyers just swapped the badges and not the engines. The 440 six-barrel setup resulted in 390 horsepower, not quite 426 Hemi power (425 hp), but quite impressive nonetheless, and at much lower cost. Even with this engine, the Road Runner came without hubcaps.

For 1969, Plymouth sold 84,420 Road Runners, quite good sales for a Mopar muscle car with only muscle engines, easily beating Dodge’s Super Bee, albeit nowhere near the Chevelle, Camaro, or Firebird (which came with nonperformance engines in base series). In 1968, GM had made 77,704 GTO hardtops and 9,980 GTO convertibles (according to the Standard Catalog of American Cars); in 1969, Pontiac made 72,287 GTOs, all together, ranging in price from $2,831 (the two-door hardtops, responsible for the vast majority of sales) to $4,212 (Judge convertibles).

Plymouth’s full page ad told all the details of the car they raced, equipped with a 440 and four-speed; it was in pure stock condition with street tires and was witnessed by reporters from Super Stock. The weight was 3,765 pounds. They had Ronnie Sox drive it, then an amateur driver, Roland McGonegal.

For 1970, the Road Runners had a new grille, again shared with Belvedere. In addition, the “Rallye” dash, with round gauges, replaced the cheaper strip gauge cluster from lower Plymouths. On the other hand, the base manual transmission was now a three-speed.

Buyers could opt for an even cheaper performance Plymouth: the 340 Duster. Dusters took Plymouth by storm, and sales of the Road Runner fell to just 43,404. Duster 340 sales were 24,817, but the regular Duster had 192,375 sales. Part of the sales drop on the Road Runner may have been due to a recession.

A new addition was the stunning Road Runner Superbird, developed in wind tunnels for NASCAR, but that’s really a different story.

The 1971 models had their first major changes, with a new body dominated by John Herlitz’s swooping lines and expressive bumper/grille fronts. The convertible was replaced by an optional power sunroof; the wheelbase dropped an inch, from 116 to 115; and engines were modified to meet new emissions rules. The 383 was hurt most, with 35 horses falling off; the 440 went down just five; the Hemi remained; and the 340 was added for a better weight balance. It’s worth clarifying that the 1971 brochures showed both gross and net power ratings—the difference being whether the engine was measured with the alternator, stock air cleaner, water pump, and so on:

The net figures would be most comparable to today’s cars. Chrysler may have fudged some of the numbers, too—whether to get that standard insurance rating or to sell more cars. Most likely the 383 was a bit more powerful than claimed. In any case, many fans see the numbers and assume that emissions controls robbed the engine of 50 horsepower and 85 pound-feet of torque, when it was just a change in methods.

The rear track widened by three inches, improving handling; aerodynamics benefited from flush door handles and vent-free side windows. Still, sales fell all the way down to 14,218. Duster 340 sales also dropped by half, though overall Duster did well. The likely cause was insurance companies belatedly figuring out that teens in hot cars equalled high costs.

Plymouth claimed that the 383 and 340 Road Runners had standard insurance ratings despite their potency; it doesn’t seem to have worked.

The 1972 models lost the Hemi and 440 triple-carburetor engine options—as did all Chrysler models; the engines were both very expensive to make, and hard to get through emissions. The 383 was bored out a bit to reach 400 cubic inches; the boring project was first done to standardize parts, but marketing people felt that 400 cubic inches would be better for sales than just-shy-of-400. Net horsepower was 255; most engines lost around 40-50 horsepower when the industry went from gross to net measurements, and that has been confused with emissions controls by many people.

On the lighter side, 1972 Road Runners had electronic ignition, which cut tuneup costs; and Road Runners were still quite potent street machines. Only 7,628 were sold, and the company changed the formula for 1973, adding the budget-V8 318, with its two-barrel carburetor. That brought down the price and insurance costs, and made the Road Runner more of a trim package. The Plymouth GTX had hung on despite slow sales, but for 1973 that car’s name went onto the Road Runner as part of an option package; to get the 280-horsepower (net) four-barrel 440 engine, you had to get the GTX option package. The changes worked, to a degree; sales rose to over 19,000.

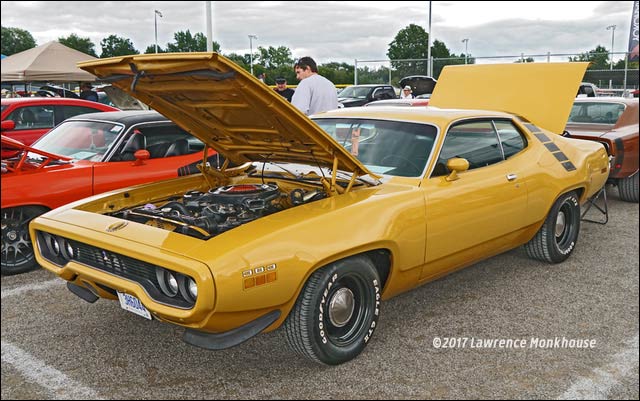

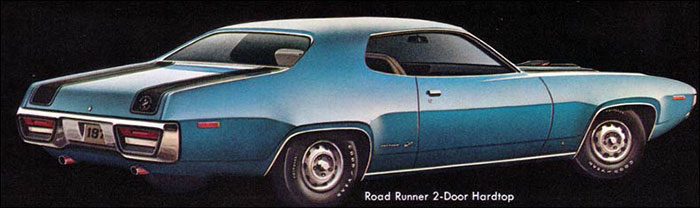

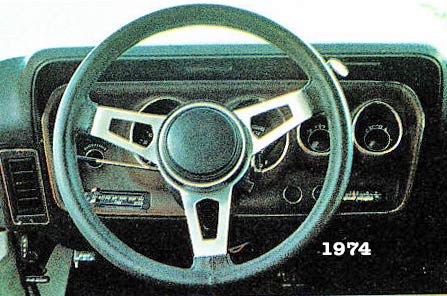

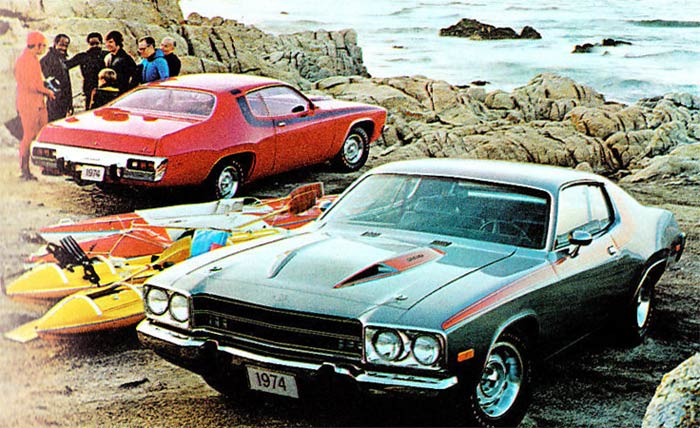

For 1974 (above), the Road Runner continued, essentially as a Plymouth Satellite coupe; buyers could still get the 400 cubic inch V8 and four-speed transmission, with a Hurst edition including the namesake shifter, and could now get the 440 four-barrel as well, without having to specify the GTX (388 were made). The 340 was replaced by the 360, a similar engine when outfitted with 340 performance parts, as it briefly was. Sales dropped back to 11,555.

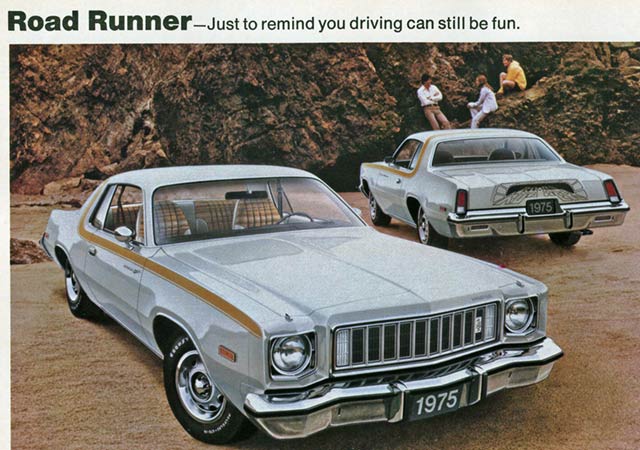

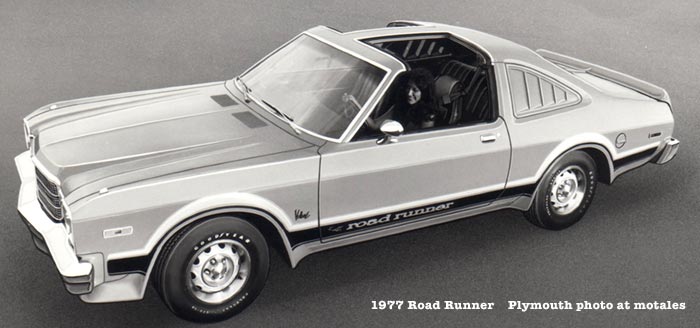

For the next year, the Road Runner switched over to the new Fury body—really, the same body with new styling and a new name; the Fury was downsized from the big C bodies to the B bodies, replacing the Belvedere and Satellite name, for 1975. Road Runner sales beat 7,000, but that was not enough to make a 1976 Road Runner, and the name was dropped. It had ceased to mean much, in any case, especially with the formal styling of the Fury. Finally, a Road Runner option package was added to the Volare body—as a trim package.

Based largely on manufacturer brochures and advertisements, The Standard Catalog of Chrysler, the Plymouth Bulletin, and Allpar.

Under the superlatives, minor changes for 2026 Alfa Romeo Tonale

Ram remains top truck of Texas

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky