Mopar (Chrysler Corporation/Group and FCA US) have made a huge number of V6 engines from their first in the 1980s to their current Pentastars. Including two Mitsubishi engines, buyers could choose from 2.5, 2.7, 3.0, 3.2, 3.3, 3.5, 3.6, 3.7, 3.8, 3.9, and 4.0 liter powerplants, depending on the year; there were even two different 3.0 engines (one Chrysler, one Mitsubishi) and two different 3.2 liter engines. Nobody had a choice from the whole list, but some buyers could choose between three different V6 engines... which brings up the question of why.

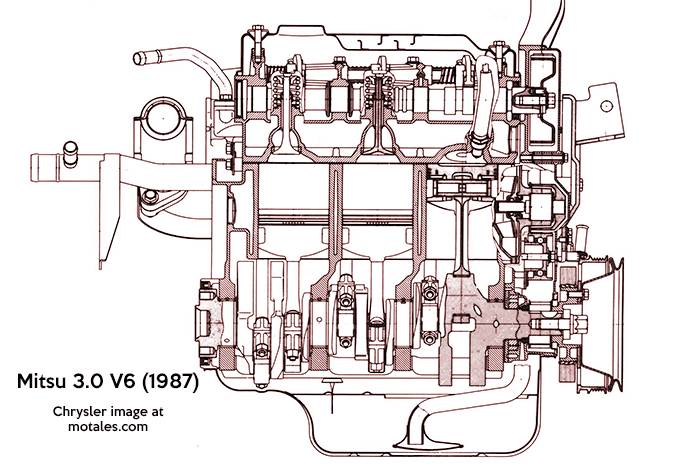

The first V6 used by Chrysler was supplied by Mitsubishi—a compact 3-liter engine, based on smaller Mitsubishi designs. It was essential until Chrysler, which had no truly compact straight-six or V8, could create their own—and stayed on for quite a while after, because the first Chrysler V6 was for trucks only, and the next was production-constrained for a while.

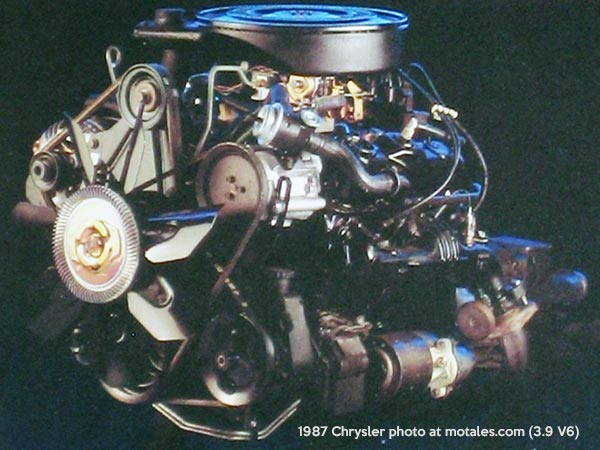

The first V6 was created in a rush, on a low budget, so the Dodge Dakota midsized pickup (itself largely created by International) could have a clear advantage over the Ford Ranger and Chevy S-10. To create it, engineers lopped two cylinders off the 5.2 liter (318 cid) V8, created new cams and such, and presto, a 3.9 liter (239 cid) engine was born.

The head engine designer, Willem Weertman, told me that, aside from speed and development cost, the V8 was a basis for the 3.9 because they could make it in the Mound Road Engine plant, where the 318 was made; the company did not have the money for a new engine line or factory. The engine bay was not large enough for the 318 itself. Chief engine tuner Pete Hagenbuch added that the vibration wasn’t so bad with an automatic, but could be felt clearly with the manual transmissions.

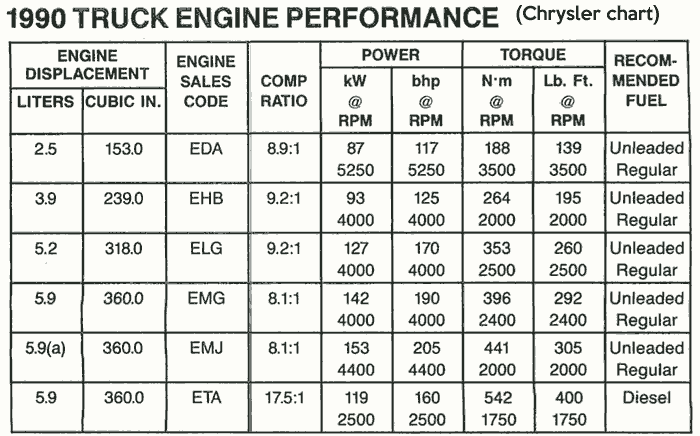

The 3.9 was used from the 1987 Dakota all the way to the 2003 Dakotas. From the start, it provided a bit more horsepower and a lot more torque than the four-cylinder engines, which fit the needs of pickup owners. A “Magnum” upgrade in 1992 dramatically boosted power and helped gas mileage, mainly by switching from to multiple-port fuel injection and optimizing the head design.

The 5.9 liter engine was not based on the Chrysler V8; it was a Cummins straight-six diesel. This chart includes both the Dakota, which started at the AMC 2.5 four-cylinder and topped out with the V6, and the Dodge Ram 1500 through 3500.

With its two-barrel carburetor, the 3.9 produced much more power and torque than the 225 (3.7-liter) slant six; not surprisingly, the slant six was quietly dropped from the lineup at the end of the 1987 model year, ending a tradition of straight sixes that was older than Chrysler itself (going back to Maxwell). The 1987 3.9 ended up being the only one with a carburetor; the 1988 version had throttle body fuel injection, and was used by the Dodge Dakota, Dodge D-150, and Ram vans and wagons. With the 1992 model year, the V6 got the “Magnum” treatment, with a major boost in power and economy. The engine always ran a little rough because it had a 90° V, like the V8 it was based on, but it was not actually replaced until the 21st century. Full 3.9 V6 story.

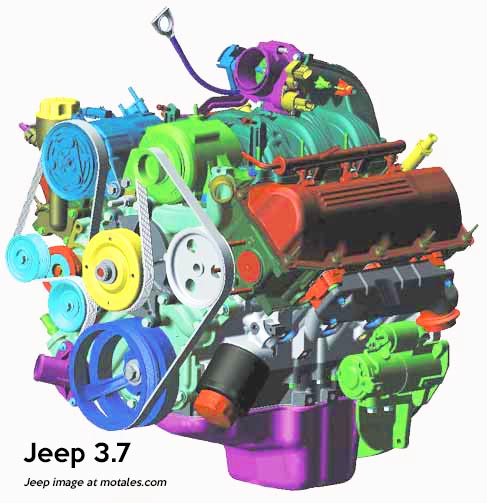

The 3.7 liter “PowerTech” engine had been in development at AMC when Chrysler bought the company; the 4.7 V8 would replace the 4.0 liter straight-six long used by Jeeps, while the 3.7 would replace the 2.5 liter four-cylinder. The V8 and V6 were closely related—just as the old straight-six and four were closely related. The older engines had been at the top of their class when new, and indeed in middle age; but much time had elapsed, and the 3.7 and 4.7 had two more cylinders (good for marketing), were cheaper to make, and passed emissions more readily. Neither engine was meant for sedans, and they were restricted to Jeeps and pickups.

The 3.7 debuted on the Jeep Liberty but within a year it was in the Dodge Ram and, another year later, the Dakota. It was far more powerful than the 3.9, smoother, quieter, and cheaper to make. A single counter-rotating, gear-driven balance shaft ran between the banks. Like the 2.0 Neon engine, the 3.7 used a lightweight composite intake manifold which boasted a very smooth air path.

A few years after launch, the 3.7 gained a number of upgrades to increase its economy and idle quality; the compression was raised to 9.7:1, and new parts included the cam, lash adjusters, and rings. It was made next to the 4.7 V8 at the Mack Avenue plant, which had been home to the 3.9 V6.

The 3.7 was the last V6 created by Chrysler, DaimlerChrysler, or Fiat Chrysler just for trucks; it would be replaced by the 3.6 liter “Pentastar” V6, which was more powerful and economical.

In the mid-1980s, customers demanded V6 engines for their front wheel drive minivans and sedans. A 3-liter Mitsubishi V6 filled in the gap, but the company needed more engines than Mitsubishi could supply; and Chrysler started working on its own design, which also provided a bit more power.

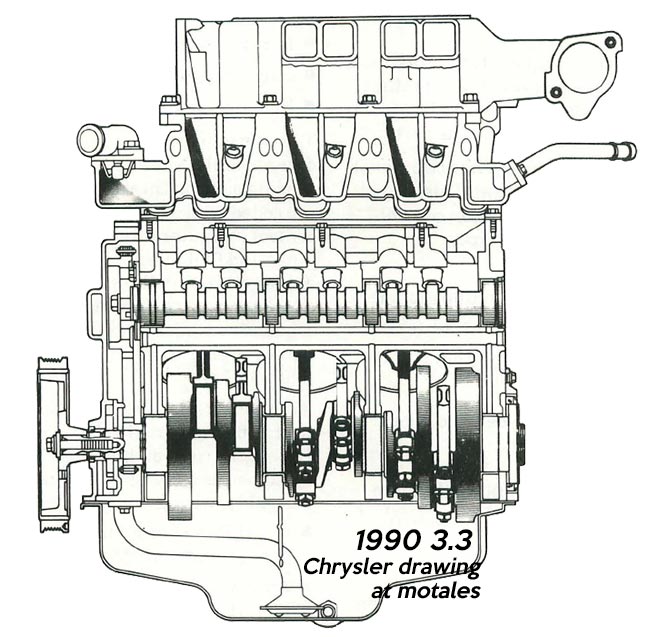

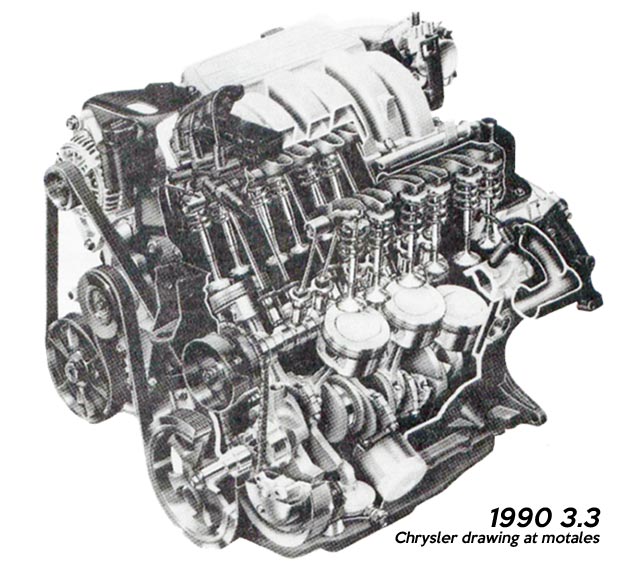

The 3.3, first used in the 1990 cars, was the first truly new V-engine Chrysler design for many years. Though overhead cams were the norm for cars, Chrysler leaders kept pushrods for their low cost and simplicity; they also stuck with two overhead valves per cylinder, to deliver torque early in the rpm range.

The 3.3 was not without its innovations, including the first use of “beehive” valves in any production car, and a distibutorless ignition system which had no rotors or distributor caps. The block was cast iron, but the heads were aluminum; fuel injection was a multiple-port design. The ports were fairly large and symmetrical, with intake and exhaust alternating on the head; there were two squish areas per cylinder, taking up a third of the bore area, when the engine was first launched. Bore was 93 mm, stroke was 81 mm, and displacement was 201.5 cubic inches (3301 cc). Injectors were in the intake manifold runners, upstream from the intake ports.

The first production 3.3 liter V6 engine was made on May 1, 1989, in Trenton, Michigan, for the 1990 cars and minivans. Small as it was, the new 3.3 had more horspower than the 318 cubic inch V8; and it had a broad torque curve, with more than 90% of peak torque available from 1,600 through 4,400 rpm, with at least 95% on tap from 2,400 to 4,000 rpm. That made it satisfactory for the minivans; so did 15% better acceleration (in the first five seconds from a standing start) than the Mitsubishi 3.0.

| HP | Torque | |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-93 | 150* | 185* |

| 1994-95 | 162 | 194 |

| 1996-2000 | 158 | 203 |

| 2001-04 | 180 | 210 |

| 2005-10 | 180 | 210-215 |

* 147 hp, 183 lb-ft in passenger cars due to air path constrictions.

Engineers found an extra 12 horsepower (and 14 lb-ft of torque) for the 1994 model year by changing the intake plenum; two years later, they sacrificed some of those extra horses in favor of a wider torque curve, dropping four horsepower but gaining 9 pound-feet of torque, and bringing peak torque at lower revs. 1994 was also the first year for the compressed natural gas version of the 3.3 engine, for fleet sales.

Major changes for 2001 brought a variable intake system (with two effective tube lengths) and new heads, with higher compression and revised tuning; horsepower shot up to 180, where it would stay, while torque rose again. Finally, in 2005, the measurement process was changed across the industry to an SAE standard; some companies saw horsepower figures plummet, but the 3.3, at least, stayed right where it was.

The 3.3 was good, but as cars were getting bigger and heavier again, something more was needed. They couldn’t drop a V8 into the New Yorker or the minivans, but they could increase the stroke of the 3.3 without much expense; thus was born the 3.8 liter engine, initially used in the Chrysler Imperial, Chrysler New Yorker, and Dodge Dynasty. In its first year, the 3.8 had the same horsepower but 15% more torque—and it was felt in lower revs. That came at the expense of some high-rev power, so the 3.8 did not feel as exciting as the 3.3 in spirited driving, but did a better job of getting heavy vehicles moving from a start or up a steep hill. It would eventually end up powering, to the shock of many Jeepers, the Wrangler.

Chrysler needed much more power as time went on, and head of Engineering Francois Castaing, who had come in with the AMC purchase, wanted Chrysler to be more technologically up-to-date. He envisioned an engine with four valves per cylinder and overhead cams, with lower displacement than the 3.8 but much more power. In the meantime, tuning chief Pete Hagenbuch had engineers produce a turbocharged 3.3 liter V6 (tested by Marc Rozman to 210 horsepower). Castaing flat-out said “no,” and while we don’t know why, two reasons come instantly to mind. First, the increasingly penny-wise Lee Iacocca was unlikely to allow the 3.5 to go forward if they already had a 210-horse V6—making the same power as the 3.5 was supposed to. Second, customers had not reacted well to the old four-cylinder turbos, and might not like a V6 turbo any more.

Work on the 3.5 started in 1989, with the intention of having it ready for the LH cars which were due in just 40 months—a tall order for an engine program. The 3.5 was loosely based on the 3.3 to save time and money, but it had more modern heads and timing—an overhead cam and four valves per cylinder, by then standard on most passenger-car engines. Gordon Rinschler, the engineer in charge of the program, set it up with a deep-skirt cast iron block, using a forged steel crank to handle the power and 10.4:1 compression ratio. Bottom-feed fuel injectors were part of the design, to make the engine small enough to fit into the LH cars; it was the first high-volume car engine to use bottom-feed injectors.

Like the 3.3, there was just one cam per head; but John Hurst designed the setup wtih dual valve rocker arm shafts so they could get four valves per cylinder. If the timing belt broke, owners need have no fear: the engine was non-interference (free wheeling), so the pistons would not hit the valves.

Spark plugs were in the center of the combustion chamber, a semi-Hemi style, with 35mm intake valves and 29mm exhaust valves;

Unlike the 3.3 and 3.8, the 3.5 required midgrade (89 octane) fuel, at least in its first incarnation; every version had sequential multiple port fuel injection and distributorless ignition (first with coil packs, then with coil-on-plug).

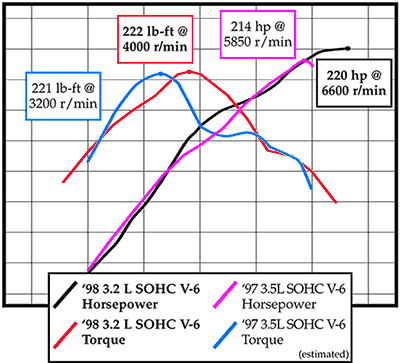

The first version produced an impressive-for-1993 214 horsepower and 221 pound-feet of torque, beating most other engines in the class above its own; the next iteration brought it to 250 horsepower, which is roughly where it stayed through the end of its life. 3.5 V6 page

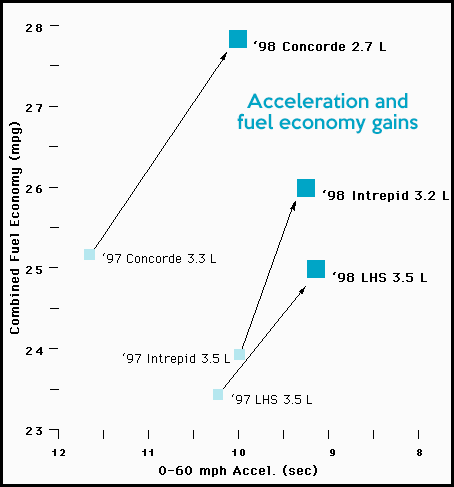

Chrysler was on a huge reinvention kick during the 1990s, eager to push forward. Francois Castaing (and some of the other engineers) were never very happy with the old 3.3/3.8 line, with their pushrods and such; they wanted more power and better economy, and a smaller base engine which could fit in more cars. For the second generation LH large cars, therefore, there was not just an upgraded, 250-horsepower 3.5 for the high end 300M and LHS; the lesser 1998 LH cars were fitted with a high-tech 2.7 or 3.2 liter V6. Both of these used twin overhead cams, replacing the clever single-cam version.

Chrysler now had an almost absurd panoply of V6 engines—the new 2.7 and 3.2; the revised 3.5; the truck 3.7; the standby 3.3 and 3.8, still serving in minivans, where torque was more important than horsepower; and, still, a Mitsubishi engine. The latter was a new 2.5 liter version of the old 3.0, making roughly the same power but with better mileage. They chose among the engines based mainly on cost and marketing (the 3.5 never made minivan duty because some where afraid it would confuse customers, since it had more power than the 3.8). In addition, Mitsubishi-made vehicles naturally used Mitsubishi engines, while most, but not all, the Chrysler-made cars used Chrysler engines. Confusing matters, Chrysler’s midsized cars used the Mitsubishi 2.5 liter V6 until the 2.7 liter engine was ready, partly because it fit under the low hood; the 3.3 was too tall for these cars. What’s more, according to Ed Poplawski, as Chrysler started phasing them out, Mitsubishi wanted guarantees that the company would still buy around 300,000 per year to keep their factories profitable. Finally, the contracts ran out and the rebadged coupes were dropped, and the Mitsubishi engines disappeared completely from Chrysler history.

| 1999 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horsepower | 190–200 | 220 | 250 |

| Pound-feet | 188–190 | 222 | 250 |

| Octane | 87 | 87 | 89 |

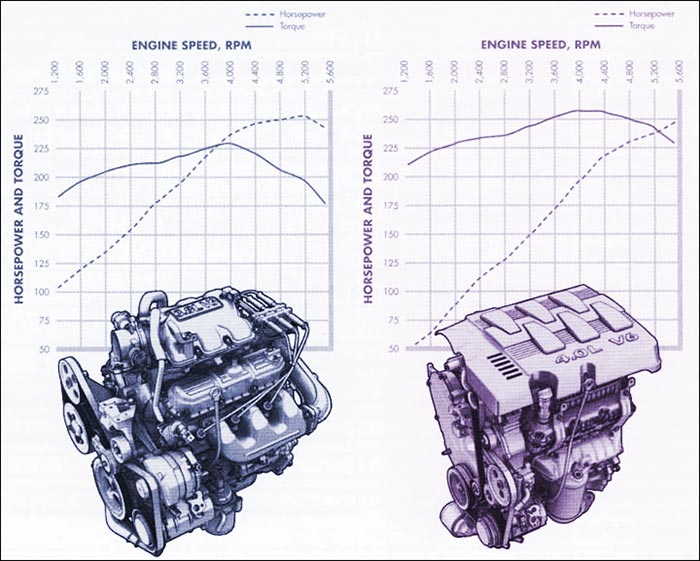

The 2.7 liter V6 was, in the words of technician Walt McCrystal, “an industry benchmark engine that Chrysler was committed to getting right.” The company published one of their rare power-and-torque charts to compare the old 3.3 with the new, more powerful 2.7; with its short stroke, the 2.7 was also engineered to rev much higher, so it was just getting started as the 3.3 had to stop at 5,200 rpm.

Compared to its larger predecessor, the 2.7 had nearly 40 more horsepower, and a tad (7 lb-ft) more torque. The 3.3 was certainly more torquey in the low revs, below 3,400 rpm or so, but the 2.7 would keep running past the 3.3’s redline. That made the 2.7 ideal for cars, and the 3.3 better for the big, heavy minivans (where it stayed—and the 2.7 never showed up).

| Car | Engine | HP | Octane | Car $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 Maxima | 3.0 | 190 | Regular | $24,675 |

| 1996 Taurus | 3.0 | 200 | Regular | $24,205 |

| 1998 Chrysler LH | 2.7 | 200 | Regular | $21,000 |

| 1997 Cadillac Catera | 3.0 | 200 | Premium | $34,750 |

| 1993-97 Chrysler LH | 3.5 | 214 | Mid-Grade | $24,270 |

| 1998 Chrysler LH | 3.2 | 220 | Regular | $24,000 |

| 1996 Taurus SHO | 3.4 | 235 | Premium | $28,250 |

| 1998 Chrysler 300M | 3.5 | 250 | Mid-Grade | $30,000 |

With the 2.7, aluminum blocks (cast with a semi-permanent mold) finally arrived in the Chrysler V6 world; iron cylinder liners assured longevity, without the expense of hardening treatments.

The 2.7 was every bit as competitive as Francois Castaing had hoped. It had more horsepower than the Acura 25TL or Nissan Maxima; while the 3.2 beat the Taurus, Cadillac Catera, and the prior Chrysler 3.5.

The new 1998 version of the 3.5 liter V6 was far higher in power than any of these other engines, with 250 horses. What's more, the Acura, Catera, and Diamante all required premium (91 or 93 octane) fuel; the 3.5 took midgrade (89 octane), and the 2.7 took regular (87 octane).

Oil sludging on early engines gave the 2.7 a bad name, but these early problems were largely resolved after a couple of years. Walt wrote, “I would have no qualms against owning a 2.7 with the improved hardware. The head gaskets and bottom-ends held up well. We had coolant-heated PCV systems on Canadian and cold-climate cars to prevent PCV icing. The water pump went through a number of revisions, including a weep hole to dump coolant outside the engine, instead of into it. By 2003, it was a fine engine, as it was intended to be.” Ed Poplawski recalled, “The production engine people busted their butts to fix all the problems.”

The 3.2 liter engine didn’t make much sense, with just 20 hp more than the 2.7 and 30 hp less than the 3.5, and was eventually dropped. The 3.3 and 3.8 were both heavily revised, providing dramatic power gains, so that all the engines were competitive—though, since Chrysler was reluctant to add the 3.5 to minivans, those vehicles were not quite as quick as their competitors.

Finally, in the waning years of the Daimler occupation, Chrysler created a larger-displacement of the 3.5 liter engine to catch up to more powerful Honda and Toyota minivan engines; the new 4-liter V6, in its second year paired with a six-speed automatic, earned Chrysler the “most economical minivan” title. This engine was first optional, with the 3.3 and 3.8 below it; then it was made standard, and the 3.3 lost its place—leaving production in 2010, five million engines after the first 3.3. The 3.8 liter engine was kept going for another year, because it had found a new home under the hood of the Jeep Wrangler.

The 4-liter (241 cid) V6 was a good engine, overall; it was a stroked 3.5 liter V6, giving more torque to an alraedy strong, efficient powerplant. It generated around 255 hosrepower and 262-275 pound-feet of torque, with a broader torque curve than the 3.5 as befitted a minivan engine (minivans weighed over two tons). Other changes, besides the stroke, cut vibration at the mounts and reduced crankshaft torsionals. To make the change, the engine had new main bearing diameters, lower-mass piston and rod assemblies, a new block and oil pan structure, less bearing clearance, and an equal-length dual exhaust. It still had the clever single-cam, 24-valve design, with hydraulic lifters and rollower followers, and a timing belt.

| (Pacifica) | 3.5 | 4.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Bore x stroke | 3.78 x 3.19 | 3.78 x 3.58 |

| Compression | 9.9:1 | 10.3:1 |

| Power | 250 hp @ 6400 | 253 hp @ 5,800 |

| Torque | 250 lb-ft @ 3900 | 262 lb.-ft. @ 4,100 |

| Fuel | 87 octane | 89 octane |

The 4-liter was surprisingly efficient pulling the minivan, turning in better mileage than the 3.3 or 3.8 had; some of that was likely due to having enough power and torque that drivers weren’t really pushing it hard, and part was being hooked up to a more efficient six-speed automatic. (Economy in the first year was relatively poor, because gearing was too aggressive; drivers had to go easy on the throttle at stop signs and traffic lights to avoid spinning the front tires.)

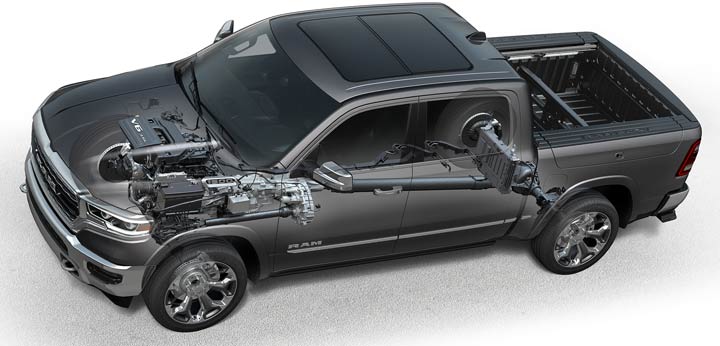

The 4.0 was a good engine, but Chrysler could, and did, do better. It started working on the “Phoenix Engine” under Daimler; continued under Cerberus, despite an aborted attempt by executives to kill the project and use Nissan engines instead; and ended up arriving under Fiat. Renamed to Pentastar V6, it was designed to replace every other V6 engine, and it did—with far fewer variations than before; there were just a few basic Pentastars, including one for the Wrangler. The engine was more flexible than the past models. Many versions of it were planned, including a twin-turbo and direct injection setup, but just three were made: a 3.0 for Europe, a 3.2 for the Jeep Cherokee, and the 3.6 for everything else, including plugin hybrid minivans.

The Pentastar was, aside from the lack of direct injection, state of the art in technology. It won a spot on Ward’s Ten Best Engines list for several years, providing considerably more power (up to 305 hp) and torque than any past Chrysler six, and doing so with better fuel economy, less noise, and easier maintenance.

The basic design was adapted by Maserati for the Quattroporte and Ghibli, pushing out 404 horsepower. While it was designed to be supercharged, though, Chrysler itself never used forced induction; the performance turned out to be disappointing (as one can guess from the twin-turbo Maserati version only having 100 horsepower more than the inexpensive Dodge Challenger version). A new straight-six, based on the corporate 2-liter, was reportedly in the works from around 2017.

This engine is still the only gasoline V6 used by Chrysler, Dodge, Jeep, and Ram; and is made in plug-in and mild hybrid form. The main points of failure, which are not especially common, are cracks in the plastic mount for the oil filter; the O-ring for one of the valve timing valves that fits into the valve cover, and is reportedly easy to replace; and the solenoid body or its O-ring.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos