When Ford came out with its V8, it wasn’t really a problem for Plymouth except for marketing. The Plymouth Six outraced the Ford V8 in contemporary road tests, but the Ford captured people’s imagination. Perhaps that seeded the idea of a Chrysler V8 in the minds of some Chrysler engineers, but the company stuck with its straight-eights and straight-sixes right until production stopped for World War II.

In 1941, the United States military needed aircraft engines in a hurry. Chrysler had stepped into the breech numerous times, saving the atomic bomb project; mass-producing Bofors guns at immense cost savings; creating their own tank engines when the normal suppliers couldn’t; and building the actual tanks, despite never having made anything like them. They even made aircraft engines. Designing aircraft engines, admittedly, was another story.

Still, company engineers experimented with the best ways to make piston aircraft engine (and for that matter, a turboprop) under Mel Carpentier, head of engine design, and Carl Breer, director of research. After making numerous single-cylinder test engines to experiment with combustion chambers, they put together their big V16 in the “Motor Room” of Engine Development and Testing, which was headed by Bill Drinkard at the time (he was succeeded by Harold Welch). The end result, retired head of engine tuning Pete Hagenbuch noted, looked just like an upside down 1951 Chrysler Hemi V8. that was no coincidence: the same people created Chrysler’s first V8 engines for cars. Willem Weertman called out team members Syd Terry, Robert S. Rarey, R. Dean Engle, Ev Moeller, George Huebner, and Herb Bevans as team members who made particularly strong contributions to Chrysler in later years; Rarey designed several of the company’s key engines.

Some of the people who worked on the V16 plane engine: Carl Breer, near the center (in a suit); George Heubner; Dean Engle; and Bill Chapman, who tested the turboprop.

The engine may have been set up “upside down” compared to car engines so they could mount cannons in the nose of the airplane, as Messerschmitts, which also ran an upside-down V-engine, did. It had fork and blade connecting rods and a central gear tower driving the cams. The output shaft drove the magnetos and propeller. The V-shape was needed to reduce the length of the crankshaft and to split the forces across two separate camshafts, while the block itself was a single piece of cast aluminum. Its included angle between banks was reported as being 60°. The propeller reduction gear was between the cranks. The engine’s uneven firing interval required special magnetos. The 32 valves were operated from a camshaft below—if the engine were flipped over (as the 1951 V8 was), it would have overhead cams like all existing Hemis at that time.

The project had no specific budget, the government having learned that Chrysler was an extremely honest custodian of tax money by then. For that reason, Chrysler made a little money on the project, while learning about hemispherical heads, porting, safety wiring, and other key issues. One area Pete Hagenbuch felt was especially important was “how to design the fork and blade connecting rods, which is a whole science in itself, in making little tiny bearing inserts, two to a rod, two more to the caps.”

Only around six engines were made. They hit their power target of 2500 hp from their 2200 cubic inch engine in 1944, an impressive number, and put their test engines through 27,000 hours of testing with two different combustion chamber designs.

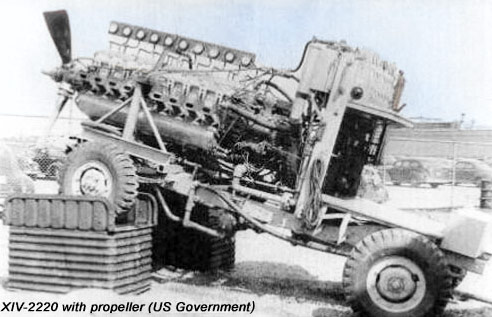

The original goal was to use a Curtis XP-60C for testing, but there were problems with this aircraft and Chrysler paid Republic Aviation to modify two Thunderbolt P47s into the XP-47H with an extended nose to fit the Chrysler 16-cylinder XIV-2220 engines. Pete wrote, “It was the damnedest-looking P47 you ever saw, if you know what the original was like.”

After 18 flight hours, the propeller shaft failed, due, engineers believed, to the sudden application of power from turbocharging. They were not able to reach the expected 490 mph, but the engine appears to have beaten 3,000 horsepower on the dyno.

Chrysler museum volunteer Marc Rozman found an XIV-2220 specification sheet which showed that the the 2,440 lb engine had a bore of 5.8” and a stroke of 5.25”; the 2,219.2 cubic inches were rounded up to 2220. The propeller gear ratio was 2.456:1 and the compression ratio was 6.3:1 on AN-F-28 fuel. It used a single-stage GE CH-5 radial “turbo-supercharger” and both an intercooler and aftercooler. These were liquid cooled. Reported power output was:

| bhp | rpm | Rating type |

| 2,500 | 3400 | Military rated power (at 25,000 feet) |

| 2,150 | 3200 | Normal rated power |

| 1,450 | 2800 | Cruise |

Fuel consumption ranged from 0.54 pounds per bhp-hour at 2,500 bhp—takeoff power—to 0.42 pounds per bhp-hour at 1,000 bhp. At cruising power of 1,450 bhp, the engine used 0.43 pounds of fuel per bhp-hour.

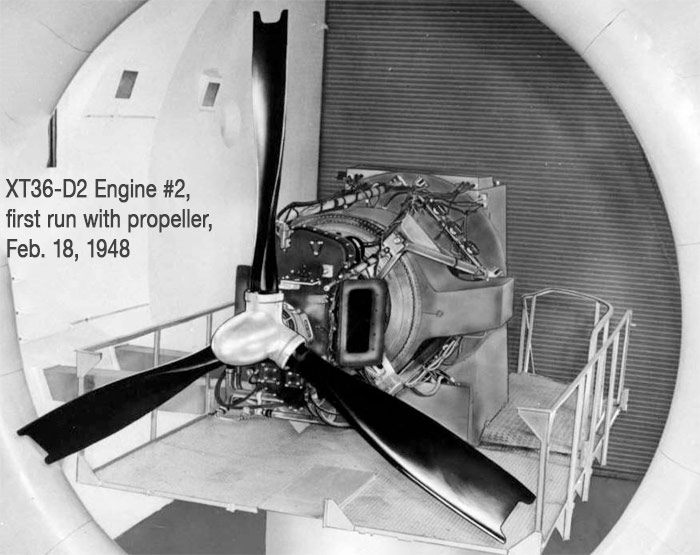

By the time the XI-2220 was ready for testing in 1944, Germany was making jet fighters in underground factories. Chrysler started on a turboprop engine in 1944, but the end of the war in Germany made further work on either engine less urgent, and the military focused on their existing aircraft makers to move forward (one of Chrysler’s turboprop engines is shown below). .

Ed Poplawski reported that he was in a small group of Racing Procurement people who found a Chrysler aircraft engine in a Ohio aviation scrapyard in 1997, and had it delivered to the Chrysler Technical Center for restoration.

Former Navy pilot Bob Eccles was part of that group; he got clearance from the group’s manager for he and Ed to work on engine restoration, on the understanding it would not interfere with their normal work.

Most of the work done was by volunteer mechanics on their own time, led by Robert Pickett. They used an empty room next to the Prototype Engine Build Shop; Ed spread the word that volunteers were needed to work on the engine on their own time. Bob Pickett, from the Engine Shop, volunteered to lead the effort, and the engine was disassembled down to a long block over the following work, uncovering quite a few rodent nests.

The company photographers were called in to take pictures of all the parts and pieces. The engine was then removed from the stand, and the stand was sent to the Paint Shop. All the parts were washed and cleaned; mechanics from the labs volunteered to hammer out all the dents and dings from the valve covers, supercharger ducting, intake manifolds, etc. The long block was sent out to be cleaned.

Their part in the restoration came to an end when their room was needed for new equipment, and the engine was sent to Roush for final detailing and painting.

According to Dan Stroud, at least two original engines have survived; the engine Chrysler acquired from the junkyard was one, but it was heavily chromed for display (by Roush), while the NASM’s Garber facility had a complete engine still on its firewall mounting—even keeping most of its Thunderbolt cowling. (Dan was collecting parts from around the world for his own P-47D project; he saved two parts from one of the original XP-47Hs, and reported seeing the original spinner backing plate and prop hub.)

Sources: Al Bosley, Willem Weertman, Ed Poplawski, Allpar, Doug Hetrick, Dan Stroud, and USAraud.ee

The Chrysler Aircraft Engines book has more background and information! (Disclaimer: we’ve only seen reviews of it—favorable reviews.)

Continue on to the turboprop engines or see other engines including the Hemi V8s

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos