It has its own factory floor, and includes dozens of test cells sitting on a separate slab. Parked on a 504-acre site, the Chrysler Technology Center (CTC) has 5.4 million square feet of floor space, enough for two Empire State Buildings. The tech center and tower, combined, cost $1.6 billion. One former engineer who had worked at R&D centers around the world, including Germany, Japan, and China, said the Chrysler Technology Center beat them all.

The CTC was designed by a cross-functional team of engineers, executives, and architects, working together; one goal was making it easier for cross-functional “platform teams” to thrive. Some joked it was designed to move Engineering far away from the executives—maybe that was not a joke, but the executives eventually came to stay.

The site includes 17 acres of natural wetlands which were left undisturbed, helping a nesting colony of great blue herons. The road runoff is directed away from the wetlands, and rainwater is guided into them. A wildlife team keeps native plants for pollination and winter cover; a series of nature trails let walkers explore the habitats.

By 1991, enough of the building was complete for migration from the Highland Park headquarters complex to begin. The basement, or Level 1, included a 3/8 scale wind tunnel, audio lab, brake lab, dyno labs, transmission test center, all sorts of shops for building prototype vehicles and mules, a fuels lab, environmental test centers, lighting test center, pilot plant, and numerous other facilities; the hallways were large enough for two cars to pass each other, so cars being tested could drive through the hallways, away from prying eyes.

Noise/vibration facilities, dynos, and some other vibration-causing labs sat on their own concrete slab, so they would not interfere with the rest of the building. Massive fuel and oil tanks sit outside, partly to feed the dyno labs. A massive transmission lab is so large it’s hard to see the opposite wall from one side of the room.

Marc Rozman running a test cell (Chrysler publicity photo, 2000)

Level 2 included Advanced Manufacturing Planning, a barber shop, computer center, education center, product design studios, product strategy and planning offices, and the offices of the minivan platform engineers and designers.

Level 3 held Advanced Manufacturing, another education center, another computer center, regulatory compliance offices, Personnel, interior design studios, vehicle engineering operations, and the offices of the Large Car platform team.

Level 4 held Procurement and Supply, another education center, offices, and the Small Car platform team.

The complex pilot production plant (“checkerboard square”), as originally created, covered 170,000 square feet, and was meant to help people get the kinks out of difficult production processes without having to leave the building (or get in the way of active plants). A full-size wind tunnel came in 2002.

The testing meant that future (and sometimes to-be-cancelled) cars could be seen years in advance of production, in testing in hallways. Prototype engines and transmissions could be found in trash bins, waiting for careful destruction.

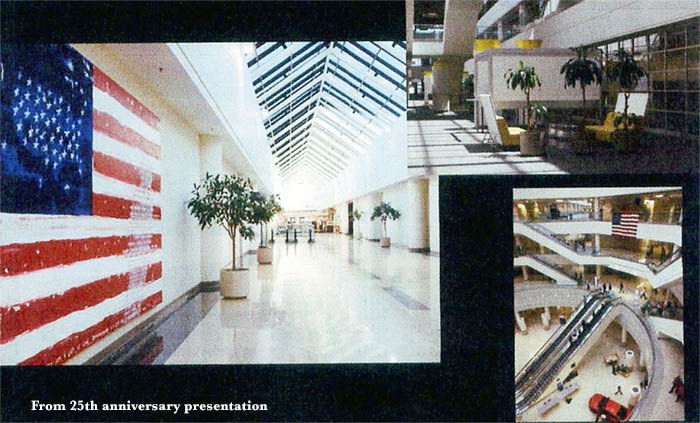

The main floors resemble nothing so much as a massive shopping mall, with huge skylights, plants, and pedestrian crossovers; signs hang from the ceilings. Some employees joked that the idea was to sell the whole building as a shopping mall if Chrysler had gone bust—which was a real danger when the CTC was first opened.

Some of the glass walls turned out to be a less well thought out idea; some employees allegedly noticed suppliers staring through the walls and at computer screens—and after that, the offices were moved around or re-arranged so nothing sensitive can be seen through the glass. Debra Walker remembered a department on the first floor adding frosted glass to prevent peekers; they had to remove it.

Ron Killen, who worked on the Mopar Missile cars, noted, “I remember our department on the top floor (SCP, Air, Fuel & Emissions). We were pretty much alone but loved it. Great memories. But, I’ve got to say I have some great memories of Highland Park as well.”

Susan Denise wrote, “If memory serves me correctly (it might not, as I last worked at CTC until January 1998, before transferring to Arizona), I thought the Computing Center was on the first, not the second, floor; I don’t recall a Computing Center on the third floor, but the Computing Staff was housed there.”

Nancy Jo Furman wrote, “I am thankful that I was fortunate to work at CTC from 1991 to 2007 when I retired. Great people, building and a great working environment. Loads of brain power and innovation throughout the company. Good times.”

Pete McLallen added, “One thing that was not considered in the CTC tower design was how to clean the huge glass Pentastar on the roof. Several cleaning contractors were consulted, and only one felt that they could handle it. It was a small company, Allied Building Supply, owned and run by a loyal Jeep owner, Tony Scappaticci, who had received their Chrysler supplier number when at the last minute they had helped the ARCAD (Jeep JJ) team move into their new facility in Livonia, across from Wonderland Mall. They were always most accommodating. As far as I know to this day they are the only ones who are willing to tackle that precarious job.”

The executive tower was added in 1993-96, to the consternation of some of the people already on-site. Platform team leader Chris Theodore, for example, told Allpar that it sent the wrong signal to employees—the rest of the building symbolized teamwork and made it easier to work in teams.

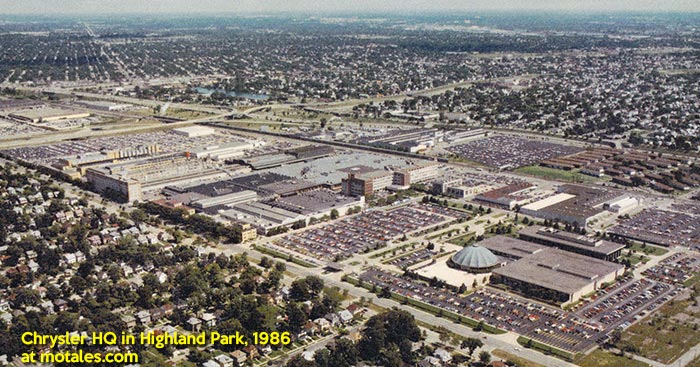

One can hardly blame the leaders of the company for wanting to move, though. Highland Park was not a particularly safe or pleasant area at the time, and it was in the middle of a large quantity of urban-outskirts-of-Detroit, with the traffic that entailed. The Highland Park complex was quite old, and while it was historic and tied them to the company’s roots to some degree, not everyone appreciates early-20th-century architecture; and the buildings were relatively small and separate. Auburn Hills, on the other hand, was a largely undeveloped suburb, and one could buy a nice mansion close to the CTC and have a minimal commute to it.

DaimlerChrysler sold the CTC and entered into a leaseback deal. Rumors claim that the Daimler people wanted to eliminate the huge pentastar built into the top of the executive tower, but the costs would have been ruinous.

By 2005, the CTC had over 8,400 employees in 2005. By the start of 2016, with the Fiat-led boom, the number was closer to 15,000. The downside of the Fiat boom was the conversion of the Walter P. Chrysler Museum, which was about as far from the CTC as one could get while staying on the grounds, into the American headquarters of Alfa Romeo and Maserati.

At least one “shaker table,” designed to put car chassis through thousands of miles of tough roads without a human occupant being shaken around, sits in the basement, constantly testing new vehicles to see vulnerable points. There are hot and cold rooms to test cars under harsh conditions without leaving the building; a hot room exposes cars to extreme UV radiation and heat to see if plastic and rubber parts fail, if the paint changes color, and if the interior materials fade or crumble. Cars can be brought from -40°F directly into 120°F if needed. Another room throws snow at cars at high speed to make sure the radiator and vents and wipers aren’t overwhelmed. There are headlight testing rooms, acoustic testing rooms, and so on. A transmission testing room is so large you can barely see the opposite wall.

On a somewhat less technical note, a styling dome (connected to a private courtyard for natural light) lets designers see cars with absolutely no reflections.

In 2015, Chysler started using 3D printing to make transparent axle housings, to compare real oil flow against computer models—which brings up memories of Chrysler’s original Three Musketeers fabricating clear valve covers at Studebaker, circa 1916, so they could see whether splash oil lubrication was working (it wasn’t). The CTC then had the highest-speed wind tunnel (160 mph) of any American car maker; they had expanded engine testing to 129 dynamometer cells.

The CTC remains a major asset for (now) Stellantis, housing numerous different kinds of labs, engineers, specialists, and generalists under one huge roof. The equipment has been upgraded and added to over time.

Also see the CTC creation stories

STLA euroshare edging up as EVs, hybrids gained

New Compass now made at Melfi (Italy)

STLA jumps into robotaxis with Uber, Nvidia, Foxconn

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos