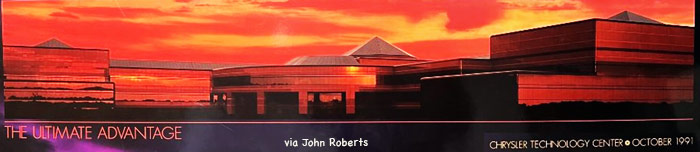

The $1.6 billion dollar Chrysler Technology Center (CTC) was a stunning achievement for a company that was apparently coming close to the edge of bankruptcy. Despite its cost, the center helped Chrysler to turn around, by supporting the “platform team” approach to engineering and by providing state-of-the-art testing and development facilities.

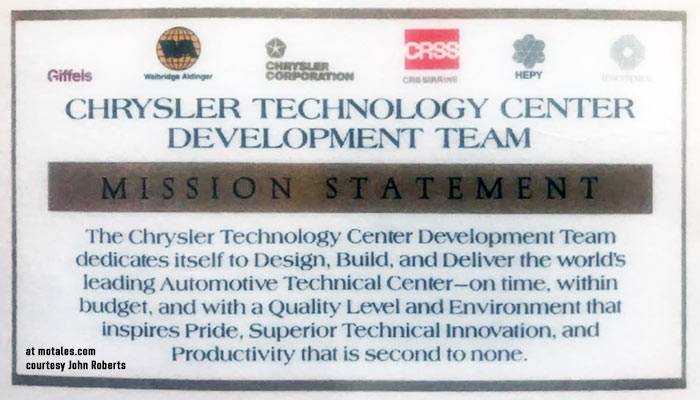

The CTC was pitched and developed by a cross-functional team of engineers, executives, and architects; John Roberts, who was with the project from start to finish, pointed out that the CTC development team was a platform team itself—the first to move to the CTC in Auburn Hills.

There were originally only 3 of us involved: Jack Gleason from Facilities, the true father of the whole concept; Gary Dysert from Facilities; and me. We started out in an abandoned bathroom in the back of Plant 4 in 1982 before the team was formally put together in the sixth story of the engineering building in Highland Park in 1984.

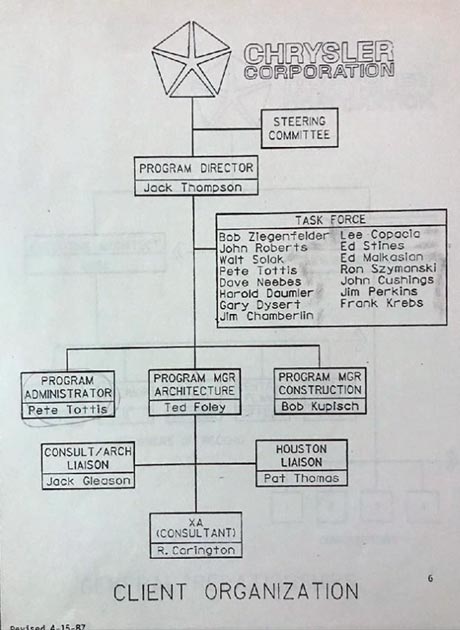

The first formal engineering team, made up of Bob Ziegenfelder and me, reported to Bob Sinclair [head of engineering before Francois Castaing] through Mike Lis. Lis then stepped aside, and Dick Torigian was brought in. His secretary was the sister and vehicle driver for Dr Kevorkian (“Dr. Death”) - but that's an entirely different story. The Executive Architect for the program, CRSS of Houston, Texas, also set up shop in Highland Park in 1984.

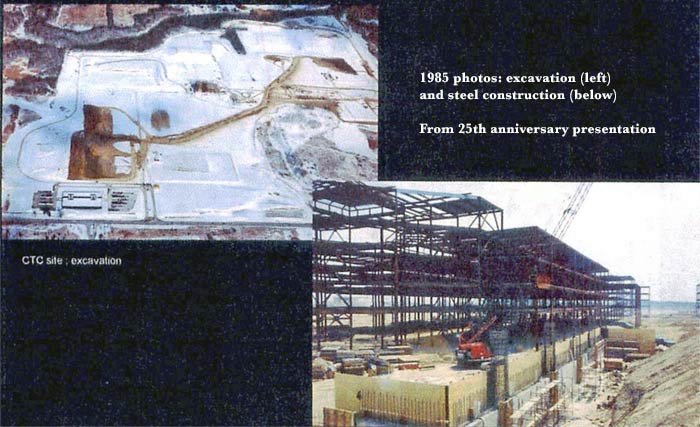

We did preliminary evaluations of the move sequence to minimize disruptions. A massive programming effort led by CRSS began, resulting first in the infamous “Black Book” (Initial Program Description) in June 1985, which set the early guidelines for the program. By this point Auburn Hills had been selected, 22 approaches had been evaluated for the center’s development, which were then reduced to four approaches for further refinement.

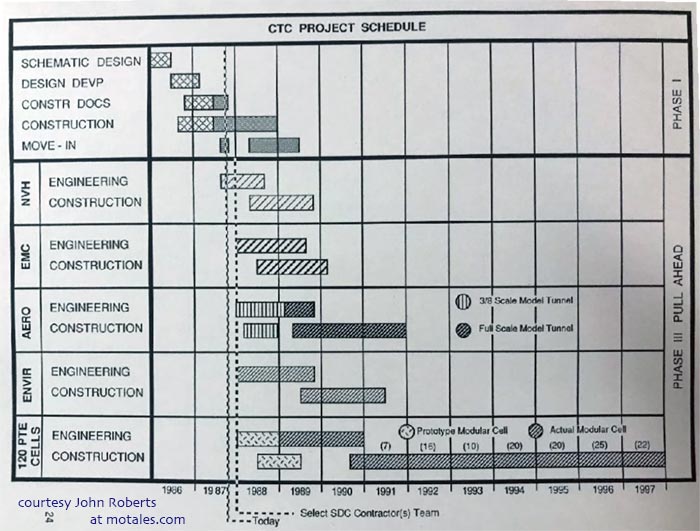

The original plan was to move technology in kind for $500 million, leaving behind the world headquarters and the powertrain dyno facilities. Engineering was not really on board with this plan. The VP of Engineering, Bob Sinclair, and the Executive VP of Product Development, Jack Withrow Sr., argued for expanding the program in early 1986; their additions were in all planning documents from this time forward. The 1986 Master Plan Summary, produced by the end of the year, included the first renderings of the site that included the major elements of the Scientific Test Facilities, except for the Full-Scale Aero-Acoustic Tunnel, which would be added at a later time.

The Chrysler Technology Center (CTC) team had cross-functional leadership drawn from Engineering, Manufacturing, Purchasing, and Finance. The team grew to over several hundred people, including architects, designers, system design and commissioning contractors, and a cadre of construction management and construction personnel. Without putting all those elements together as a functioning stand-alone team, CTC would have never happened.

The formal ground-breaking event occurred on October 30, 1986, chronicled in the November 6, 1986 edition of The Chrysler Motors Times. By September 1987, the components of the Scientific Test Facilities had been specified and an RFP released for the creation of a new industrial partner, the Systems Design and Commissioning Contractor. The projects were not well enough defined to go for a “turn-key” approach, so we elected to develop a new project delivery approach to maximize flexibility and to take advantage of the structure we had already set up interfacing to an executive architect, construction manager, and owner representatives.

The original Director of the CTC Development Team, Jack Thompson, left just after construction had begun, to lead one of the early product development platform teams. The next director was James Clancy, from Manufacturing, who headed the group for all of Phase I and the initial phases of the scientific test facilities. I worked directly for him from 1988 until he retired.

The program was formally extended from $500 million to an approved $1.6 billion by the Board of Directors in mid-1988. The CTC Development Team moved to the Auburn Hills site at about the same time; our on-site location was the C.O.B. (Construction Office Building), quickly renamed from the S.O.B. (Site Office Building) for obvious reasons.

During our financial hardship times, I was tasked by Bob Sinclair to find someone who could design, build, own, run, and lease back to us all the facilities that we needed for CTC. Such a team was put together by Sumitomo (a $70 billion consortium), but we never had to go that route because of the fortuitous acquisition of American Motors, followed by a period of economic prosperity unlike any we had seen for a long time, if ever.

The hologram in this chunk of glass, which was passed out at the CTC groundbreaking in 1986, has somehow managed to survive for close to 36 years.

This thing is hewn out of about a 3”x3”x3” block of solid glass.

I’m nearly the last of the senior members of the team still on the earth plane. I was the “youngster” at the time; the others were all at or approaching retirement age, and doing CTC as their “last hurrah” for the Chrysler they had served for their entire careers. I was 40 at the time, there as the initial engineering rep driving the technical facilities advancement that would become the Scientific Test Facilities. That was the focus of my career from 1982 until my retirement in 2002—also as a youngster, of 55 plus one day.

The groundbreaking ceremony itself was held in a tent, and included senior executives such as Lee Iacocca, who gave a speech. Then an automated digging machine symbolically started the process of putting up the massive complex.

By the time of Chairman Lee Iacocca’s retirement in 1992, a great deal of the space was being used productively by the new platform teams. The initial phases of the Scientific Test Facilities were under construction, with the Noise Vibration and Harshness facility, Electromagnetic Compatability facility (EMC), Initial Powertrain Wing A, the 3/8 Scale Aerodynamic Wind Tunnel Pilot and the Initial Environmental Test Center (including hot and cold driveability chambers, vehicle and engine altitude chambers and emissions testing) completed and comissioned by the close of 1994.

James Clancy retired around 1992; a lot of dirt had been moved around and facilities built under Jim’s able direction. He was followed by Mel Young, from Manufacturing, until Mel’s retirement and the final transition of the complex to the CTC Facilities group for the final push starting in 1994.

From 1995 to 1999, we saw the completion of heavy investments in construction and commissioning of Powertrain Wings B, C, D, and E. The design of the Full-Scale Aero-Acoustic Wind Tunnel was completed in early 1999, with construction getting under way by the end of that year and basically completed by the end of 2001—with the extensive commissioning process taking place in the first half of 2002. This facility was then formally commissioned in July 2002, marking the completion of the Scientific Test Facilities.

There were definitely some parallel things going on that brought about the successful implementation of CTC. There were those who optimized the use of the facilities as the platform concept was introduced, like Chris Theodore, Dick Torigian, Dr Jack Thompson, and others; and then there was the CTC Development Team that sold the concepts, developed the program, specified, designed, constructed and commissioned the facilities. This was an effort that spanned 19 years under four different directors, starting with Dr Jack Thompson; the final piece was the commissioning of the Full-Scale Aero-Acoustic Wind Tunnel in mid-2002.

It seemed quite ironic to me that the engineering leaders who sold the introduction of technology into CTC never made the move to CTC themselves—Bob Sinclair and Jack Withrow Sr., who retired in 1987 and 1988, respectively. I took them both on independent tours through the facility after their retirements. By then I had become the Program Manager for the specification, design, construction and commissioning of the Scientific Test Facilities stationed in the COB at the CTC site, working for Jim Clancy.

Susan Denise wrote that Jack Thompson was instrumental in developing the platform team approach to product engineering, along with Bernard Robertson and Francois Castaing.

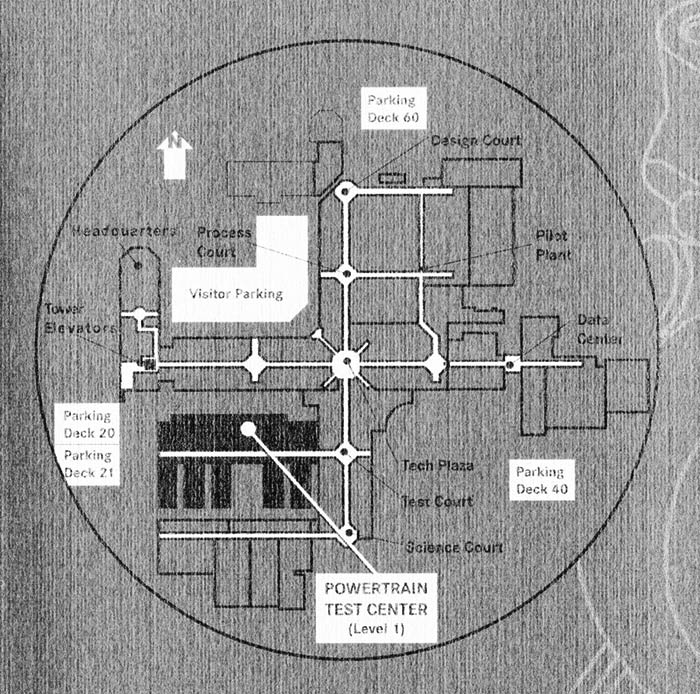

Chris Theodore, John Miller, Craig Winn, and Dick Torigian were charged with final changes and planning the move. Chris Theodore told Marc Rozman, “That’s when we came up with the idea of using the crucifix [to support platform teams], putting one platform team over the other, aligning body engineering over body engineering, etc.” At that time, too, there was no provision for the floors to hold the weight of cars, and no way to get cars in and out of the ground floor—the idea of testing cars in the hallways hadn’t been born yet.

Theodore said, “We were very proud of the way that was arranged... I think it’s one of the best facilities in the world. The only bad part of the facility—the honest-to-God truth—is all the executives in Highland Park at the six story building. They got lonely down there and they got jealous. So Bob Eaton and company decided that they had to move to CTC.”

Chris Theodore later added, “I have to admit that I originally thought Lee was wasting money on CTC when we were in such dire financial straights, but it turned out to be one of the greatest enablers to creating the team’s cultural change.”

Debra Walker added, “During construction, CTC was the largest construction site in the world.” She also recalled a brief plan to make all employee parking “first come, first served,” but she added, “our director hated that idea. It never happened.”

Debra also noted that “There was a need to convert several of the majority-men’s restrooms to women’s rooms.” Paul S. Gritt confirmed: “I was on the Small Car team, one of the first to move to the top floor of the north wing. We were at Highland Park, looking over the blueprints of the suite we would in, and noticed that none of the bathrooms were for ladies! There was a scramble and changes were made.”

While the CTC was being built, and indeed after it was completed, Jeep/Truck Engineering (JTE) continued at the Plymouth Road facility—the old Kelvinator building; but, Pete McLallen reported, “engineers travelled to CTC in the early 1990s to talk with workmen about their pickups (likes and dislikes). Several features gleaned from those conversations made it into the final T-300 (BR) [Ram 1500] design, like more room in the cab behind the seat. This was an unintended side benefit of building CTC.”

By the time they were done, there were 15 specialty test cells (hot, cold, diesel, semi-anechoic, heat rejection, altitude with 13,100-foot capability, and so on); 32 rear drive test sites, most having 450-horsepower, 8,000-rpm capable dynos, and including eight RWD transmission durability sites, six catalyst aging sites, four for performance, two for heavy truck certification, one for diesel, and one for race engine development wtih two dynos (one going up to 1,000 horsepower and 16,000 rpm). That was on top of 18 engine performance cells (four having cold-fluid capability), 16 powertrain durability cells, and four emission development cells; and 44 cells for engine durability and reliability.

The CTC is a major asset for (now) Stellantis, housing numerous different kinds of labs, engineers, specialists, and generalists under one huge roof. For more, see our main Chrysler Technology Center and World Headquarters page.

Under the superlatives, minor changes for 2026 Alfa Romeo Tonale

Ram remains top truck of Texas

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky