The year was 1966, and Chrysler’s most recent brand-new engine was the 170/225 slant six, released in the 1960 cars. The new Valiant had taken the US and Europe by storm, and was rejuvenating Chrysler Australia—to the point that, when Australia phased in domestic content requirements, Chrysler was ready to make their parts, including engines, locally. They would only have money for one engine family.

Their V8 engines were considered, but they were too heavy and costly. The slant six was the next possibility, but they would need larger, more powerful engines fairly quickly, and the slant six could not be made much larger than 225 cubic inches. They needed a light inline six-cylinder which could be sold in small and large sizes.

Chrysler’s engineers at the Highland Park headquarters had started a new six-cylinder in 1962; the idea was to use the LA V-8 engines’ bore (3.91 inches) with sizes up to 265 cubic inches, for large cars and trucks. They had tried several designs—one with an overhead cam, one with conventional overhead valves, and one with pedestal-mounted rocker arms. Starting in June 1966, they started working on this engine for Australian sale; Highland Park would develop the basic design and make a few prototypes, then turn the program and a few test engines over to Chrysler Australia’s team, led by Mike Stacey. The new program code was A167.

Unlike the slant six, they kept the engine upright, because it was simpler. The American group thought about using a raised deck version for trucks, with around 300 cubic inches of displacement, but ultimately never went there.

Head of performance tuning Pete Hagenbuch told Allpar’s David Zatz that they designed the engine in new-to-Chrysler way: “We had always designed bulletproof engines and nobody ever knew how much lighter they could have been. So this one it was done the other way”—designed to be as light as possible, with the idea that they would find problem areas and beef them up as needed.

Pete related, “The oil pan fell off of the first engine. Not literally, but there were only two screws left holding it, the block was so floppy.” It was a long engine with a big bore; the distributor was in the rear, so the long cam’s torsional vibrations went through the camshaft and into the distributor. “That was terrible, they had to work and work and work on the cam and the cam drive... the cylinder walls were thin, everything was thin. There was a lot of beefing up in the pan rail and the main bearing bulkheads... but it was a hell of a good engine.”

He added that they applied what they learned on the LA V-8 to the new six; “I think those lessons carried over then into the Australian engine that was designed and into the 2.2. We sort of went through the lightening process once and then we applied those lessons to all of the future engines.”

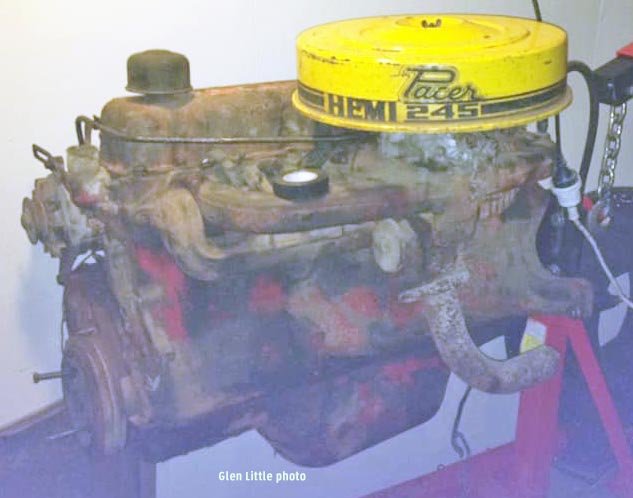

Despite placing a premium on light weight, they did not use aluminum blocks, though Chrysler had some experience making aluminum slant sixes; that may have been an economic issue, as yields were far higher with cast iron. The heads were also cast iron. Intake and exhaust valves were in-line; valve stems were canted to the front and rear for better airflow and to accommodate the semi-hemispherical heads; according to Willem Weertman, in Chrysler Engines, credit for this goes to R. Dean Engle, head of Power Plant Engineering. The head design allowed Chrysler Australia to use the Hemi® trademark on the six-cylinders.

The engine used ball stud rockers; Pete Hagenbuck wryly commented, “Fortunately, I didn't have to make them work ... our advice to the manufacturing plant was to form the ball socket, coin it, and then coin the rocker pad and the push rod socket in one operation. Our stamping plant said, ‘We can’t coin those two surfaces at the same time! Hell, Highland Park is nuts,’ so they didn’t try to do it. The rockers were all over the map. Valve lift varied [quite a bit]... when they finally bit the bullet [and followed our advice], ... it was fine—just like we designed it and tested it.”

The engine was largely conventional—an inline, iron-block straight six with pushrod-activated valves and hydraulic lifters. Single-carburetor versions had combined intake/exhaust manifolds topped with carburetors. The long crank had seven bearings. The main difference from other sixes was in the heads—a near-hemispherical design, to get the highest performance from a given displacement. Chrysler had pioneered mass-produced Hemi V8 engines starting in 1951, and by this time they had even refitted its biggest V8 with hemispherical heads for racing. The head design was not new for them; but it gave the Australian engines an edge.

Pete Hagenbuch recalled that, after Highland Park finished and delivered a few 245 engines, final development was done in Australia. There was a hitch, though: the Australians weren’t able to run endurance testing for more than 20 hours. When he arrived to troubleshoot, he found that they were running wide-open-throttle endurance tests, as Highland Park did—but, in his words:

They were using car spark plugs, for Heaven’s sake, hot spark plugs, the ones that keep from fouling while your wife tootles around at 30 mph. Wide open throttle endurance at Chrysler has always been run with just about the coldest spark plugs that you could find or that Champion would make for you. We weren’t testing spark plugs, we were testing the engine structure.

He swapped in the coldest plugs they had, and the engine passed endurance tests before he left Australia.

The truck engine never saw the light of day, though it would have been handy later on. Willem Weertman said the costs would have been too high, including production, given the projected volume; they did design studies but never even built an experimental engine.

While even the 215 cubic inch “kangaroo six” outpowered the 225 slant six, which was still fairly new at the time, Chrysler never seems to have considered selling it anywhere but Australia and New Zealand. The higher performance wasn’t needed for North America, where cheap gasoline meant anyone interested in performance would use a V8; and in Europe, it was too large for most cars. The decision may seem odd, given that Spain sold a decent number of Valiant-based cars powered by the 225 slant six; one would think that the 245 or 265 would be well-received. However, the cost of making and fitting that engine may have been too high; and it wasn’t suitable to a luxurious car, since the engine had to be revved high to get good performance. The slant six, with its low end torque, was more suitable.

In South America, the 245 or 265 would likely have been a competitive edge; and one does wonder about how high the costs may have been to increase production in Australia and ship the engines out to Brazil and Argentina, which had to make do with slant sixes topped by dual single-barrel or two-barrel carburetors.

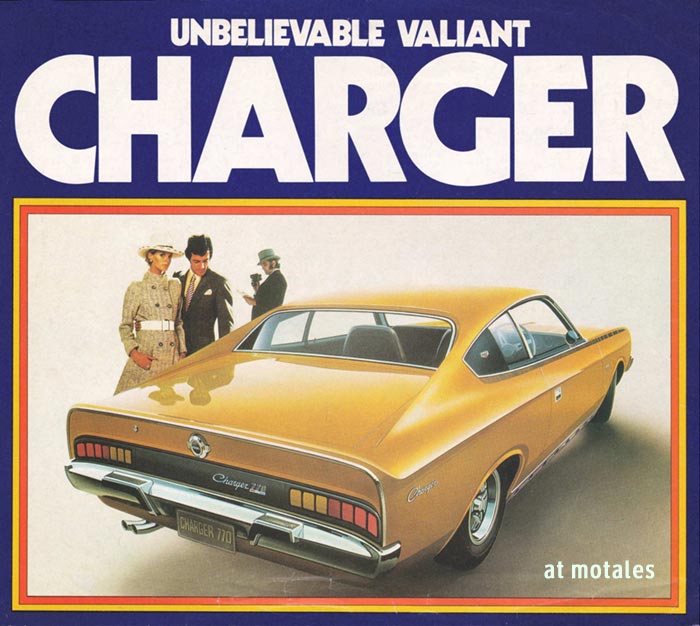

Chrysler Australia built the “Kangaroo Six” (as many of the American Chrysler people called them) locally for derivatives of the American Valiant, including the sporty Valiant Pacer and Valiant Charger.

Initial development was done in the United States on the 245 in single and two-barrel froms; Australia took over from there, according to Willem Weertman. The 245 cubic inch engine started production in 1969, in Lonsdale, Australia. Wheels compared the Valiant to the Holden and Falcon (GM and Ford) entries, and noted that the Valiant “runs away from the others” in the six cylinder market. Another magazine ran the standard retail two-barrel 245 in a VG Valiant Pacer to an 8.1 second 0-60 time with a 17.5 second standing-400 meter (400 meters is just shy of a quarter mile), hooked up to a three-speed manual transmission with 3.23:1 axle.

| VG 245 | Power | Torque |

|---|---|---|

| 1-barrel (1V) | 165 | 235 |

| 2-barrel (2V) | 185 | 240 |

In addition to the single- and dual-barrel 245s listed above and the standard 195-hp two-barrel Pacer, there were several 245 variants:

On the opposite side of the performance range, another late addition was the 215 Hemi. Its lower compression enabled it to burn regular fuel rather than Super, and it was only sold with a one-barrel carburetor. This engine started out in the Valiant VG in 1971.

The next Valiant was the VH, the first to be entirely made in Australia with Australian parts. It seems fitting that the VH was the first to have the new 265 Hemi. The new Valiant Charger, a lighter-weight coupe version of the sedan, proved to be a fine platform for getting the most out of the new engine.

The 265 was planned from the start; after all, one goal of the new design was originally to have a 300 cubic inch version for Dodge Truck, since Ford and Chevrolet both had six-cylinders of around this size. The idea was for Chrysler Australia to make the 300 cid version and ship it back to the United States; executives, however, refused to make that investment, and there was no truck version (some stories mangle this by claiming that the Australian six-cylinders were abandoned American truck engines).

All the Kangaroo Sixes had the same stroke, with different bores; the 265 was engineered to match the American 318 V8’s bore so they could share pistons, but for technical reasons this did not happen.

| Engine | Bore | Stroke | Liters | Intake Valve |

Exhaust Valve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 215 | 3.52 | 3.68 | 3.523 | 1.84” | 1.5” |

| 245 | 3.76 | 3.68 | 4.014 | 1.84” | 1.5” |

| 265 | 3.91 | 3.68 | 4.342 | 1.96” | 1.6” |

E34 and E35 four-barrel manifolds for the VG Pacer had a cast-on water heating setup for the plenum, so they don’t need exhaust heat; the manifold was used as it was cast, with no heat riser flap, shaft, or channel. All Hemi manifolds were a log type with one or two outlets, and a bridge tube between the middle two cylinders—until the CM series, which was separated for cylinders 1-3 and cylinders 4-6.

What was not planned from the start was a hot version of the 265 Hemi featuring triple carburetors, each having two barrels (or two venturis, depending on how you look at it)—this “Six Pack” (3x2) was well beyond what the Highland Park experts thought the engine could stand. The name was taken from Dodge’s label for the triple-carburetor 440 V8 (it was also applied to a single-year-only version of the 340 V8).

Developed in Australia, with carburetor tuning in Italy by Chrysler and Weber engineers, the engine skipped the usual slant-six-style intake manifold in favor of tubes going from the carburetors two cylinder pairs. Side-draft carburetors were needed because there was not enough room above the engine for downdraft Carter two-barrels. Each carburetor had its own air filter, fitted at 90° angles to their normal arrangement.

Pete Hagenbuch recalled that “it turned out it was a very good engine though we had thought it was a little bit too much for the structure.” Yet, the ultimate E49 version of the engine pushed out a stunning 302 horsepower and 320 pound-feet of torque, performance V8 territory.

The first version of the 265 “Six Pack,” the E37, was rated at 248 horsepower and 305 pound-feet, with 9.7:1 compression. The concurrent E38 version increased compression to 10.0:1, resulting in 280 hp and 310 lb-ft. The highest power version, the E49, released in mid-1972, had the same 10:1 compression. It propelled the E49 Charger to a 14.4-second quarter mile—an Australian production-car record that stood until 1988—with a 0-60 mph time of just 6.1 seconds. The VH Valiant Pacer also set a record, as the fastest-accelerating six-cylinder four-door production car made in Australia, which also stood for quite a while.

This photo shows a 265 Six-Pack being tested on the dyno at full throttle, without air cleaners. The red-glowing tubes were not retouched—they were that hot.

There were, in short, four Six Pack versions of the Kangaroo Six, all painted gray and blue. All of them used blocks from the regular 265 line—but technicians chose particular blocks which met the specifications most closely. They had a high-mass vibration damper to deal with the crankshaft’s torsional virbrations; tin aluminum main bearings with full circle oil grooves; a bushing on the small end of the connecting rods; and different pistons, with a small crown added to boost compression and circlip grooves for fully floating pins.

The concurrently-made E38 went further, adding deeper main bearing caps, longer bolts, and hardened washers. The crank was shot-peened in some areas for greater hardness; connecting rods were shot-peened for fatigue resistance. The pistons were further altered to hit the desired a 10.0:1 compression ratio. All four of the Six-Packs had tubular fabricated headers. (The E48 engine was an E37 coupled to a four-speed manual transmission.)

The ultimate Kangaroo Six, the E49, was similar to the E38; again, they modified the pistons to reduce clearances, and added intermediate piston rings. These pistons also had molybdenum-filled tops.

In 1972, Modern Motor took the E38 Valiant Charger to 60 mph in 6.3 seconds, with a 0-100 of 17.2 seconds and 14.8-second quarter mile; that beat the Ford Falcon GT (351 V8) and Holden Monaro GTS (350 V8). The 245 Hemi two-barrel pushed the Valiant through the quarter mile in 16.4 seconds, while the Pacer two-barrel, ran it in under 16 seconds. This beat many V8 engines (though the numbers for the two-barrel are improbably fast). The E49 ran the quarter (in Sports Car World) in 14.4 seconds, with a 6.1 second quarter-mile that is still competitive today. Yet, they wrote, “It’s so fuss-free that your mother could puddle back and forwards to the supermarket.”

Production of these engines ended in 1973, at the end of the Valiant VH series, as public sentiment turned against high-performance engines; they were only ever sold on the VH and VJ series, and all their efforts only yielded roughly two years of production. Most of the Six-Packs stayed in Australia, with most of the exports going to New Zealand; none went to the United States, except long after the cars had been sold to their first owners.

The VG’s single-barrel cam was a 248-244-22 design; the two-barrel used a higher-performance 256-252-30 setup. These were kept, unchanged, in to the VH range. The E34 (272-272-48) cam took on a new role in the E38, while the all-out E49 used a new cam, a hot 308-308-88 model. These were the four cams used in the first (VG and VH) models:

| VH | Intake Opens (BTC) | Intake Closes (ABC) | Exhaust Opens (BTC) | Exhaust Closes (ABC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 215+245 | 12° | 56° | 54° | 10° |

| 245+265* | 15° | 61° | 57° | 15° |

| E38 | 18° | 75° | 62° | 30° |

| E49 | 40° | 88° | 80° | 48° |

* Used first in the VG 245 two-barrel engines, this became the standard cam for the VH 265; the new 265 relegated all 245s back to a single-barrel carburetor and economy camshaft. until the VK. After the VJ, compression was dropped and cam profiles were softened until the ELB.

By the VH range, all 215 and 245 engines had single-barrel Carter carburetors, while the highest-performance 265 engines had three side-draft Weber 45 DCOE two-barrels (and were dubbed the “Six Pack,” as with Dodge triple-carburetor engines). The economy 215 engine was the only one with a manual choke (the rest were automatic chokes)—and the only one that could take regular gasoline instead of Super, at least until the 1976 model-year. All used paper air cleaners and 35-amp alternators.

Once the VH series came out with its 265 Hemi, the 245 engine was relegated to a single-barrel carburetor, until much later in the late VK series, when they returned to a two-barrel.

Even the smallest Kangaroo Six, the 215, with its single-barrel carburetor, had output similar to the 225 slant six (140 bhp and 200 lb-ft vs 145 bhp and 210 lb-ft) but it weighed less, and that was the absolute lowest-power economy version of the series. At least one ad showed the 215 as having 216 cubic inches, but that must have been a typo—3.523 liters is 215 cubic inches.

The 245 was a more mainstream engine, with a similar carburetor of 9.5:1 compression and output of 165 hp and 235 lb-ft—output far beyond the 225 slant six, and, again, with a single-barrel carburetor. The base 265 (arriving in the 1971 Valiant VH series), with its two-barrel carburetor, was good for 203 hp and 262 lb-ft.

Equipped with the 245 six-cylinder and a two-barrel carburetor, the 1970 Valiant VG could run the quarter mile in 16.4 seconds; the Pacer, with a four-barrel carb, could do it in under 16. For 1971, the 215 was standard on the base Valiant and Charger; the 245 was standard on the Charger XL and optional on Charger; and the 265 was optional on the Charger XL, and standard on Charger 770 and R/T. The CH Chrysler by Chrysler started with the 265. Some models, such has hardtops, where there was no low-price model, did not have an available 215 at all.

| 1971 265... | Power | Torque | Comp. | Carb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemi Six | 203 | 262 | 9.5:1 | 2V |

| HP Hemi Six | 218 | 273 | 9.5:1 | 2V |

| Street 6 Pack | 248 | 306 | 9.7:1 | 3x2V |

| Track 6 Pack | 280 | 318 | 10:1 | 3x2V |

Note: all figures are gross (bhp) rather than net and do not compare directly to modern engines.

The normal single-barrel and two-barrel Hemi Six had a single-outlet exhaust; the high performance version had a dual-outlet exhaust, with the exhaust manifold going from six cylinders to one and then having dual outlets.

The (1971-73) Six Packs had special extractors; the 248-hp version had a single exhaust and the 280-hp version had a dual exhaust. The 318 V8 two-barrel, incidentally, produced 230 hp and 340 lb-ft of torque—more torque than any of the Hemi Sixes, but less horsepower than the triple-carburetor packages, with a single exhaust and 9.2 compression.

The automatic transmission was dubbed TorqueFlite, but most were actually a Borg-Warner Model 35 produced in Australia, used by numerous companies including Ford and Leyland to meet local production rules. Four-speed manual transmissions were made at the same plant, for the same reason—each automaker producing their usual transmissions for Australia would be too expensive. Chargers (other than the 215) had a floor-shift; other models could have a three-speed (column or floor shift) or four-speed floor-shift. Late-production (CL / CM series) cars with the V8 could have the four-speed manual, but not the three-speed manual; earlier V8 cars always had an automatic.

| 1973* | Power | Torque | Comp. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 215 | 140 | 200 | 8.1 |

| 245 | 165 | 235 | 9.5 |

| 265 | 203 | 262 | 9.5 |

The basic single-barrel engines were tuned for torque at lower engine speeds; torque peaked at 1800 rpm for the 215 and 245, and 2,000 rpm for the 265. The performance versions (all but single barrel) had much hotter cams, and required a good deal more revving to reach peak torque. The 265 two-barrel, good for a 15.7 second quarter mile and 218 hp (273 lb-ft), had peak torque at 3,000 rpm; the top engine, the E49, didn’t reach peak torque until 4,100 rpm.

| Engine | Carbs | BHP | Torque (lb-ft) |

C/R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 215 | 1V | 140 @ 4,400 | 200 lb-ft @ 1,800 | 8.0:1 |

| 245 | 1V | 165 @ 4,400 | 235 @ 1,800 | 9.5:1 |

| 265 | 2v | 203 @ 4,800 | 262 @ 2,000 | 9.5:1 |

| 265-HP | 2V | 218 @ 4,800 | 273 @ 3,000 | 9.5:1 |

| E37/E48 | 3x2V | 248 @ 4,800 | 305 @ 3,400 | 9.7:1 |

| E38 | 3x2V | 280 @ 5,000 | 310 @ 3,700 | 10.0:1 |

| E49 | 3x2V | 302@5,600 | 320 @ 4,100 | 10.0:1 |

... and measured performance:

| Carbs | bhp | 1/4 Mile | 0-60 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2V | 218 @ 4,800 | 15.7 sec | |

| E38 (3x2V) | 280 @ 5,000 | 14.8 sec | 6.3 sec |

| E49 (3x2V) | 302@5,600 | 14.4 sec | 6.1 sec |

The 1971 Valiant Charger E38 Hemi’s performance was similar to the 351 V8-powered Ford Falcon GTHO, with “exceptional” handling due to the light engine. The 1972 E49 Charger was a step forward, with its Borg-Warner four-speed manual gearbox; its 302 bhp six gave it the quickest acceleration of any Australian production car (14.4 seconds in the quarter mile). Racer Leo Geoghegan commented that the Charger E49 R/T, which included a performance suspension, handled well on the track straight off the assembly line, while most cars needed a great deal of tuning.

Australia’s first emissions standard for cars limited carbon monoxide to 4.5% of the exhaust volume. The emissions rules tightened quite a bit in 1974, capping carbon monoxide at 100-220g per test (filling a bag), and limiting hydrocarbons to 89-12.8 g/test. These limits were also quite “doable” for most existing engines. The next rule, taking effect on January 7, 1976, was more serious: it limited unburned hydrocarbons (to 2.1 g/km), carbon monoxide (to 24.2 g/km), and oxides of nitrogen, linked to smog (to 1.9 g/km). These limits continued into the 1980s.

To meet the 1976 standards, Chrysler both dropped compression and added emissions equipment, which sapped power a bit; for those reasons, they replaced the 215 economy six (the only Hemi taking regular fuel) with a lower-compression version of the 245 Hemi in the Valiant CL and later Valiant CM, starting in 1976. The lower compression in that special 245 was required to use regular fuel rather than Super.

Lean Burn, a more clever way to meet emissions standards, launched in the 1978 Valiant CM series, with all engines (including the V8). The two-barrel 265 with Lean Burn was tested to run a 9.6 second 0-60 mph and 17.5 second quarter mile; the 1971 Valiant with 265 two-barrel had run a 15.7 second quarter mile, so this was quite a drop. The GLX was a heavier car, which accounts for part of the slower times.

The GLX may not have been able to race down the straights as well as past 265 Hemi Six-Pack cars, but it could take turns better: it boasted an upgraded suspension tuned for radial tires. Drivers could, with some effort, achieve over 30 miles per Imperial gallon.

| 1978 | Carbs | Net Horsepower | Torque (lb-ft) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 245 | 2V | 111 @ 4,400 | 190 lb-ft @ 1,800 |

| 265 | 2V | 146 @ 4,800 | 212 @ 3,000 |

By this time Australians had switched over to net power measurements, so there is no direct comparison between the 1978 and 1970 engines; but usually the change from gross (bhp) to net ratings only cut 30-40 horsepower off, so emissions equipment was clearly having an impact—but emissions alone didn’t drop it from 218 to 146 hp. Chances are the emissions gear took around 30-35 hp off, and the rest of the performance gap in acceleration, compared to prior Valiants, was due to the car’s weight gains.

CM Valiants of 1978-81 used a dual outlet manifold; there were two designs, a one-piece and a two-piece which was designed to stop them cracking due to their long length (the way that slant six manifolds often do).

The end was signalled in 1980, when a financially strapped Chrysler Corporation sold its entire Australian business to Mitsubishi Motors. Chrysler was already making some Mitsubishi cars in Australia; the smaller, more-efficient cars were more amenable to local demand, and Mitsubishi had expected to be fully acquired by Chrysler over time. With Mitsubishi in charge, the Kangaroo Sixes and the Valiant were both dropped in 1981, after an all too brief but altogether honorable life. Sadly, Mitsubishi disposed of a good amount of Valiant development records over the years, too.

Thanks to Willem Weertman’s definitive Chrysler Engines and to Gary Bridger and Gavin Farmer’s excellent Hey Charger, available at Amazon (U.S.) and Pitstop (AU/NZ)