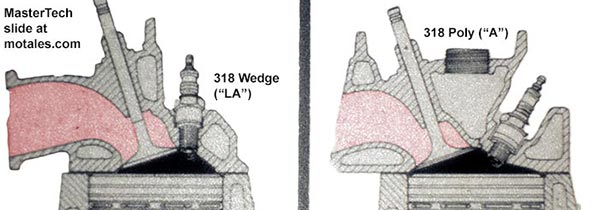

Work on the 1960 Valiant started in mid-1957. It took very little time to discover that Chrysler did not have an engine that would fit inside, and company leaders commissioned a new six-cylinder. When they needed a V8 in the same car, the engineers decided to adapt one they already had: the big, heavy “A-series” V8. Fortunately, a Chrysler foundry had learned how to cast blocks with thinner walls, cutting fifty pounds of weight. Add new heads, and you have the LA, for Lightweight A, V8 engines.

The story of converting the former hemi-head engines into polyspherical head engines is already on Motales; so is the story of converting the “poly” into the first wedge-head LA engine, the 273. But what happened after the little 273 was born? Quite a bit, as it turns out; while the 273 didn’t have a long run, its bigger brethren did.

The second LA engine kept the 273’s stroke (which was also the stroke of the A-engines), but had the bore of the A-series 318 “poly” (or “wide-block” or “waffle-head” 318). The result was the LA series 318, which replaced the A-series 318 in United States-built vehicles for 1967 and in Canadian-built vehicles for 1968*; both the two-year phase-in and keeping the same displacement caused some confusion then and now. Keeping the bore and stroke did reduce tooling costs.

* Production for the 1967 model year would usually start around August 1966, for example.

Chrysler did not change the power ratings when they went from A to LA, though it’s quite highly unlikely the two engines actually had exactly the same output at the exact same revolutions. (We checked the output figures from the 1962 A-series 318 all the way to the 1971 LA-series 318 to confirm that this was not a temporary gaffe.) Output ratings, as usual in that period, were suspiciously round, regardless.

| USA Spec | ’68 273 V8 | 318 |

|---|---|---|

| BHP @ 4400 |

190 | 230 |

| Torque | 260 @ 2000 | 340 @ 2400 |

| Compression ratio |

9.0 to 1 | 9.0:1 (1966) 9.2:1 (1968) |

| Bore | 3.63 | 3.91 |

| Stroke | 3.31 | 3.31 |

| Carburetor | 2-bbl. | 2-bbl. |

| Fuel | Regular | Regular |

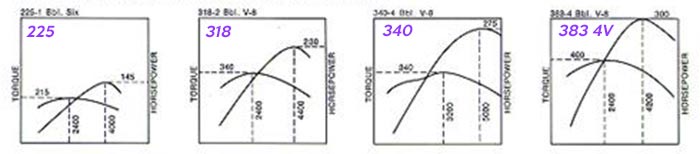

The LA 318 started out with hydraulic lifters, which did not need regular adjustments, unlike the A-series 318 (or for that matter the original LA-series 273). For the most part, the 318 was not a glamour engine; most LA 318s drank regular fuel and provided decent torque, economy, and reliability by the standards of its day. High performance 318s were not needed in 1967 because of the 273 four-barrel, and they were not needed in the 1968 and most later years because Chrysler had an engine specifically made for high performance. The hot 340 produced a likely underestimated 275 bhp and 340 lb-ft—and more in 1970, with a “Six-Pack” setup. The 340 was later used as the basis of the most potent LA engines ever: the race-only 355 V8.

Dodge trucks started using the LA 318 with the 1967 models; it replaced the LA 273 and A 318 in vans, compact trucks, and medium duty trucks. Two truck versions were produced, both of which had some changes to increase durability. Lower-grade truck engines were designated by a -1 (318-1) while heavier duty upgrades were dubbed -3 (318-3). The -1 series’ most notable alteration was probably the water-heated crossover in the intake, replacing the exhaust-gas-heated crossover—a crossover which tended to clog over time. The tougher -3 series gained 18mm spark plugs instead of 14mm, exhaust valve rotators, higher-grade intake valve alloys, and heavy-duty bearings.

Dodge’s truck division listed a different, and probably more accurate, horsepower rating: 210 bhp (20 bhp less than in cars) in vans and light-duty trucks—a step above Dodge Truck’s 202-bhp rating for the old A-series 318.

Dodge Truck pointed out that the new LA 318 weighed 10% less than its predecessor, while developing more power and torque. For medium duty trucks, Dodge provided a probably-accurate 212 bhp, 322 lb-ft rating. The LA 318 was standard on the medium-duty C-500, D-600, tilt-cab L-600, and school bus S-550 and S600 models; it was optional on the D-400 and D-500 pickups, W-500 4x4 pickup, and S-500 bus.

| Trucks | ’66 318 | ’67 318 |

|---|---|---|

| BHP | 202 | 210 / 212 |

| Lb-ft | 322 @ 2800 |

The 1969 model year brought a more reliable manifold heat control valve (with replaceable valve shaft bushings and a replaceable stainless-steel internal seal); a special solvent could be squirted through the vent holes to keep the valve operating freely.

Power output in 1970-71 was listed as 230 bhp and 320 lb-ft of torque; horsepower figures were the same as in 1967, but torque was down by 20 lb-ft, due to a drop in compression to 8.8:1. The cause of this was likely emissions tuning.

The 318’s first known net horsepower figures were released in 1971: 155 hp and 260 lb-ft of torque (compared with gross figures of 230 bhp and 320 lb-ft). A drop in compression to 8.6:1 for the 1972 cars dropped 5 hp from that rating, settling it to a neat 150 hp, while torque dropped slightly to 255 lb-ft. In California, all Chrysler engines had an oxides-of-nitrogen (NOx) control system. Since these were mainly produced during acceleration, engineers fought them with a greater valve overlap in the cam, a later centrifugal advance (via a new distributor), and a lower-temperature thermostat (185° vs 195°).

| 318 | Net hp | Net lb-ft |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 155 @ 4,000 | 260 @ 1,600 |

| 1972-76 | 150 @ 4,000 | 255 @ 1,600 |

| 1977 | 145 @ 4,000 | 255 @ 1,600 |

Phased in through the 1972 model year, Chrysler started hardening the valve seats (heating them to 1700°F, then rapidly cooling them) to prepare for the arrival of unleaded gasoline, and setting up the exhaust gas recirculation (where equipped) so it would only come on when the engine could deal with it. The 1973 cars, and then the 1974 trucks, gained standard electronic ignition systems, making breaker points obsolete.

Further changes to meet tougher emissions standards resulted in a 5 lb-ft loss in 1975 (at 255 lb-ft), while the horsepower rating dropped by 5 hp in the 1977 cars due to changes in the spark advance curve. The 318 joined its first Chrysler, the new Cordoba (which was based on the midsized B-bodies, not normally a Chrysler platform), as an option for fuel-conscious buyers.

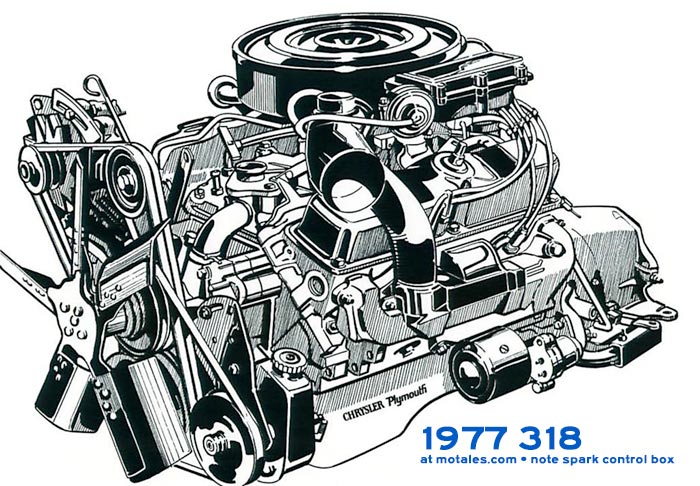

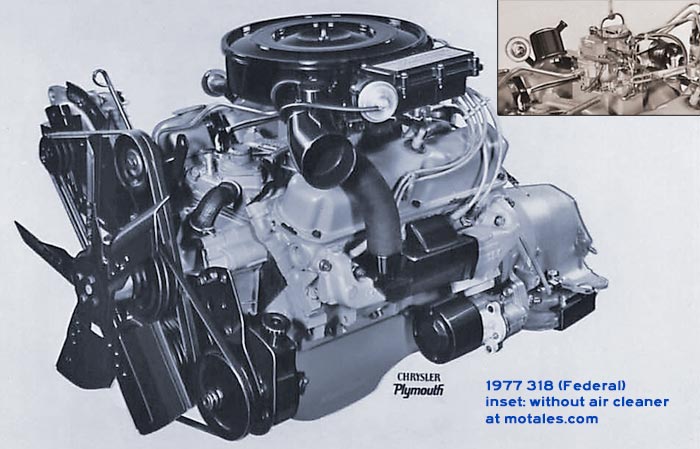

Starting with the 1977 model-year, 318-powered cars sold in high-altitude areas had altitude-adjustable carburetors. Lean Burn (electronic spark control, in these early years) joined the 318 in late 1977, except in California. Chrysler service techs saw a new service bulletin advising them to learn how to service the Holley 2280, a new-to-Mopar two-barrel carburetor earmarked for 318 ELB engines with automatic transmissions with federal and Canadian emissions. The bulletin claimed that the Holley 2280 was extremely similar to the Carter BBD, except for its aluminum casting and differentiating the curb idle and fast idle adjustments by using a slotted hex-head screw for the curb idle and a cross-head screw for the fast idle.

Some blocks at this time were cast by International Harvester, which cast their logo onto the block, because Chrysler was now selling far more of their smaller V8s given higher fuel prices.

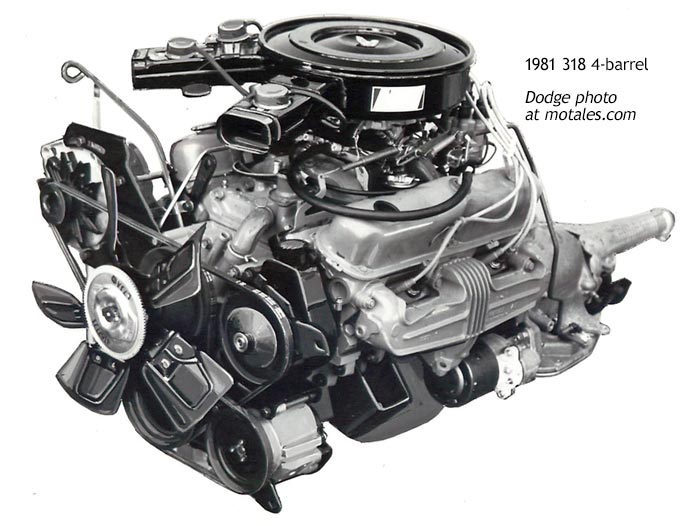

The 1978 model year brought adapters for magnetic ignition timing measurements (timing lights still worked) and a second-generation Lean Burn system. New carburetors were half a pound lighter than the previous models; they used “solid fuel” operation, meaning that a stream of fuel was fed to the primary discharged nozzles and mixed with air there, allegedly to help with lean fuel-air mixtures. A new police four-barrel was introduced, given the phase-out of the big-block engines; this was the E48 package, with high performance “J” heads, dual-pickup distributors, windage trays, and double-row timing chains. Over time the engine would be upgraded as the police put it to the test, getting better seals and valve guides. The four-barrel setup made for a fast enough police car that many Diplomat/Gran Fury-driving officers thought they had a hot 360 under the hood. (The related 360 also had an E48 package, confusing matters somewhat).

Chrysler tested customer acceptance of a 318 in a Chrysler with the 1978 Cordoba S, a lower-cost Cordoba with the smaller engine; customers must have liked it, because the 318 was standard in the 1979 Cordobas. In addition, to counter the effects of primitive emissions controls, 1979 and later California and high-altitude cars had 318s with four-barrel carburetors.

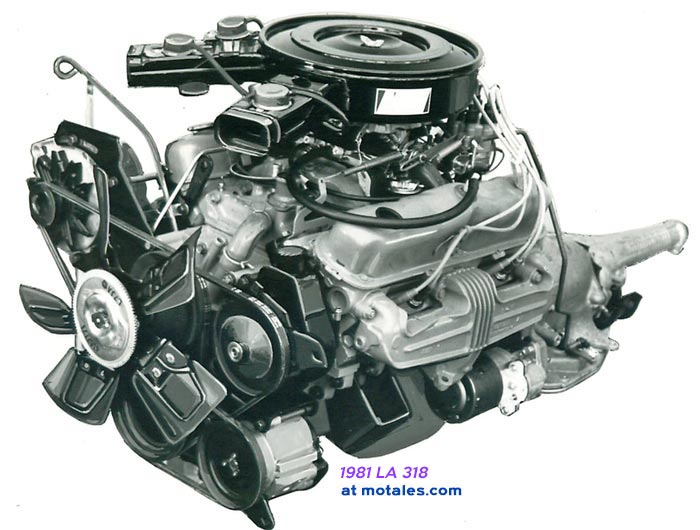

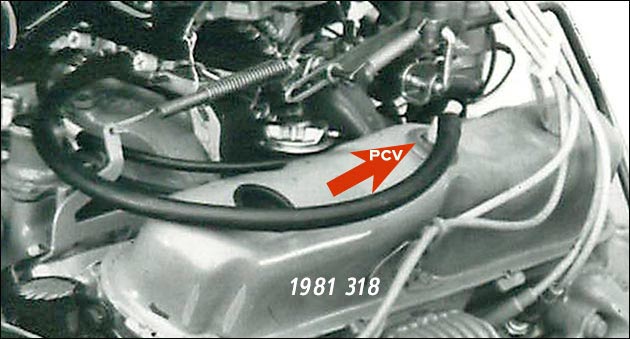

The 318’s block, cam, exhaust manifold, and rear main bearing cap were all changed to save weight for the 1980 model year. Then, starting in mid-1980 (calendar year), production moved to Mexico, making room for new four-cylinder engines at Trenton. It must have been a busy time for the engineers, especially given changes for the 1981 model year.

First, the 1981 passenger cars could no longer have the 318’s bigger brother, the 360; instead, the 318 was available with the California four-barrel carburetor setup and a new intake. These changes increased output to a healthy 165 hp and 240 lb-ft of torque. Police cars could still have the 360 all the way to 1984; and the two-barrel 318 was still available.

Next was a propane fuel system for the Dodge Diplomat, meant for fleet buyers. Propane was economical but provided less power and required large tanks in the trunk—yet, many taxis were equipped with propane power. It was a product of Chrysler Canada engineers, installed at the plant and covered by the warranty.

Finally, the 1981 Imperial’s 318 was equipped with an odd new electronically-controlled fuel system. The system was rushed through development, with engineer Richard Samul working out of a tent for some of its design phase. Rather than fuel injectors, the system used a spray bar with a continuous flow of fuel, varied by changing fuel pressure. Samul wrote that it was affected by magnetic fields, such as those created by roadside power lines, which made the mixture too rich at part throttle. Dealers switched most of the cars over to carburetors under warranty; it was a shame, because the system was apparently smoother than the two-barrel setup, and with a little additional investment may well have slashed maintenance costs and ended many drivability issues. Power output was similar to the two-barrel, at 140 hp and 240 lb-ft.

In 1983, rated power dropped to 130 hp and 230 lb-ft in the United States, due to emissions tuning and equipment; the compression ratio was now down to 8.5:1. The police engines were updated somewhat with new heads, still coded J, but with larger coolant passages.

For 1984, the police engine package was recoded from E48 to ELE, but appears to have largely stayed the same. In the following year, when Carter stopped making carburetors, Chrysler chose the E4ME Rochester Quadrajet to replace it in the police 318.

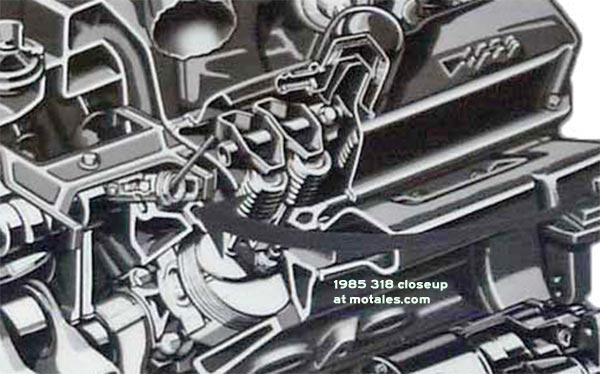

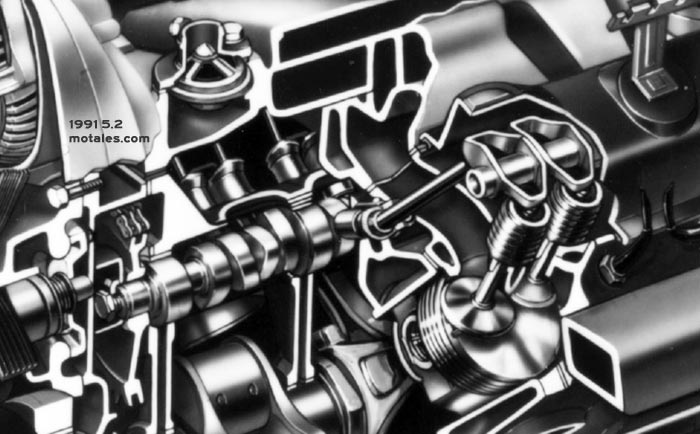

As oil makers phased out zinc, automakers had to drop their flat tappets in favor of “roller lifters.” Chrysler replaced the 318’s camshaft and lifters with roller designs starting with the 1985 cars and 1987 trucks. Roller lifters tended to have much less wear from cold starts; they could also control valves more precisely, allowing a steeper cam profile.

At the same time, given that the 318 was now used solely in upscale cars, Chrysler raised the compression in passenger-car applications from 8.7:1 to 9:1. Chrysler reported:

For 1985, the 318 V-8 has been re-engineered to provide an 8% improvement in basic engine fuel economy. The fuel/air burn rate has been increased by adding valve shrouding to the combustion chamber, by an increase in compression ratio to 9.0-to-1 over the previous ratio of 8.4-to-1, and by a lower friction valve gear system.

Pete Kranz noted,

The E48 heavy duty four-barrel 318 received the heads, intake, and carb (but not the cam) from the E58 (the top engine in the J, M, and the brief run of 1981 R-bodies). The E58 was every bit as underrated as its 340 predecessor. The 1978-80 F-body Volare Pursuit was quick, running hotter through the lights than the 1978 Fury 440 Pursuit in testing (though the Fury had a good 10 mph over the Volare at the top end).

Output rose from a dismal 130 hp to a somewhat more respectable 140 hp; torque had a bigger lift, going from 235 to a hefty 265 lb-ft. These numbers remained for passenger-car 318s from model-year 1985 until their final model year, 1989. The downsides was that premium fuel was required from 1985 onwards. Fuel economy figures were somewhat isolated from reality, as Chrysler used axle ratios to game the figures (e.g. a 2.2:1 ratio in 1985 big cars). The net result of that today is that swapping in a more suitable axle ratio “wakes up” a vintage 318-equipped Diplomat, Newport, Gran Fury, or Fifth Avenue more than quite a bit of engine work would; and when we look at the gas mileage figures from the 1980s, we see grossly inflated numbers compared to what most drivers might achieve. It was possible to get 28 mpg out of a Diplomat, but not easy.

Trucks were not retuned for premium fuel, and continued to use regular gasoline.

| 1984 | 1985 | |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel | Regular | Premium |

| Power | 130 hp | 140 hp |

| Lb-ft | 235 | 265 |

In Canada, the car 318 was still rated at 150 hp and 265 lb-ft of torque at least through 1987, possibly due to lower emissions standards.

Skip to the “final 318-360 years” for the rest of the story.

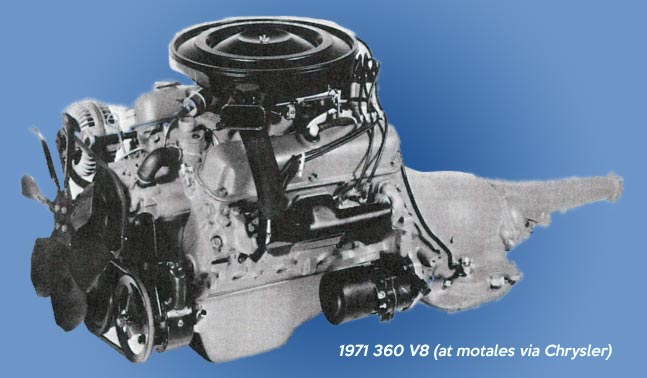

In 1970, Chrysler’s V8 line started with the 318 V8 (not including the high-performance 340, which had a limited audience); then it jumped to big blocks starting at 383 cubic inches. Product planners wanted something lighter than the 383, with more torque than the 318, still able to drink regular octane fuel. The bore could only be brought up to 4 inches; to buy more displacement, the stroke was lengthened to 3.58”, making it the only LA engine without a 3.31” stroke. Head of engine development Willem Weertman later wrote that they thought about bringing back the 361 cubic inch B engine, which would have been easier, but decided that would be too heavy and expensive.

The longer stroke caused many complications. The automated block machining and assembly lines couldn’t handle a raised deck, so the engineers shortened the pistons and changed the crankshaft counterweight radius to make more room at the bottom, allowing greater travel in the same exterior space. That kept block changes to a minimum, but threw the engine off balance.

To rebalance the engine, the engineers had to add weights to the crankshaft assembly, change the flywheel and torque converter flex plate, and add an offset weight on the vibration damper. Other changes included using higher-diameter main journals to handle more power with the nodular iron crank, to avoid using an expensive forged crank like the 340. Core hole and spark plug locations were shared with the hot 340—which would be handy just a few years later—but not the 318.

Production started in mid-1971 in Windsor, Ontario. The 360 started out with a two barrel carburetor, a mild 252-256-32 cam, and gross output of 255 bhp and 360 lb-ft (net output was 175 hp and 285 lb-ft)—right between the 318 and 383. The compression ratio was 8.8:1, low enough to take regular fuel. In an advisory to service technicians, Chrysler wrote, “The engine has mild valve timing, large induction and exhaust passages, and hydraulic tappets. The cylinder block has thicker bulkheads. Main bearings are farther apart and longer than the 318 CID engine, from which this new engine has been derived.”

Willem Weertman wrote that, since it was lighter and cheaper than the 383, the company made the 360 the optional engine in the 1971 Dodge Polara and Plymouth Fury, and the base engine in the Chrysler Newport Royal; these cars were all on the same “C” body as the biggest Chryslers. He also wrote that Chrysler buyers did not think it was an appropriate choice, so the 383 was quickly restored as standard—the 1972 Chrysler Newport Royal had a standard big-block V8. It did end up in Chryslers with the 1975 Cordoba.

Trucks gained the 360 as soon as it was available; changes from the car engines included all the upgrades made to the truck 318s, except for water-heated crossovers in the intake manifold.

Of note, AMC also had a V8 engine displacing 360 cubic inches, which was used in the final “SJ” series Wagoneers—potentially confusing once Chrysler acquired AMC, in 1987—and Chrysler itself had made a big-block engine displacing 361 cubic inches.

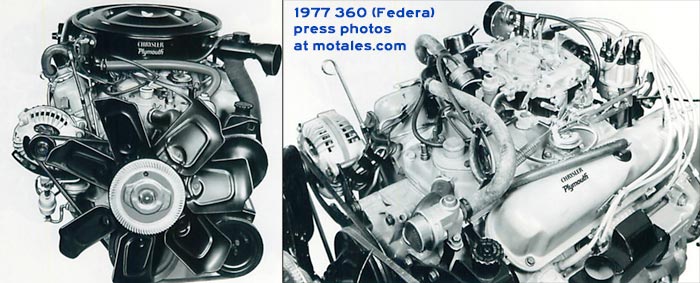

When the 340 was dropped at the close of the 1973 model year, engineers closed the gap by adapting the 340’s ThermoQuad four-barrel carburetor and its hot 268-276-44 cam. That combination brought power levels up to 245 hp and 320 lb-ft of torque, beating the 1971 340 four-barrel’s 235 hp and 310 lb-ft. It was a respectable performance engine, especially for 1974—and despite 8.4:1 compression.

The 360 with the E58 package is especially impressive considering that the standard four-barrel 400 V8, an evolution of the 383 B-engines, only made 205 horsepower; admittedly, the 400 had more torque at lower revs, and had higher-performance versions. As Pete Kranz wrote,

The E58 360 was a heavy duty/high performance fleet engine developed to replace the 340 in 1974. It was mostly used in B, F, and R-body police models through its discontinuance in March of 1980, but it was also in some high performance models (such as the 300), including the B, F, and J bodies, and the 1978-79 LRT (as the EH1)—but not in the M-body.

A new version of the 360 launched in 1974 was meant partly for trucks; it used a four-barrel but not the hot cam, and was rated at 200 hp and 290 lb.

With the 1975 model year, the 360 (two-barrel) became standard on the Cordoba (the brochure has it in the Newport but the dealer data book does not). A new 1975 California four-barrel variant was rated at 190 hp and 270 lb-ft. The California four-barrels had smaller primaries for better economy, the standard short-duration cam, a catalytic converter, and an air pump. This setup lasted to the final year of the 360 in cars. The Duster and Dart’s optional high-performance 360 continued with the hot cam, now rated at 230 hp and 300 lb-ft of torque; police could order special “J” heads as well. This “hot” four-barrel continued on through 1979.

| 1976 Valiant | 225 | 318 V8 | 360 V8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low speed pass | 475 feet 11.0 sec |

460 feet 10.5 sec |

405 feet / 8.6 sec |

| High speed pass | 2090 feet 24.8 sec |

1480 feet 16.2 sec |

1245 feet 13.3 sec |

For the 1978 cars, dual concentric throttle return springs were added to the torsion throttle spring; air pumps could be ordered outside of California with the N96 emissions control package.

| 1978 | 318 Fed | 318 CA | 360 2V | 360 E58 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carb | BBD | BBD | BBD | TQ |

| HP (net) | 145 @ 4000 |

135 @ 4,000 |

155 @ 3600 |

220 @ 4,000 |

| Lb-ft | 245 @ 1600 |

235 @ 1,600 |

275 @ 2000 |

280 @ 1,600 |

The company’s big block engines were dropped at the end of the 1978 model year, making the 360 Chrysler’s biggest and most powerful engine for 1979 (and only for 1979). By then, output was down to 195 hp and 280 lb-ft. However, given that the police needed a high performance option, a new E48 police package was created for both the 318 and 360, launched for the 1978 cars in preparation for the end of the 400 and 440. They shared high performance heads, dual-pickup distributors, double row timing chains, windage trays, and other durability measures; as reports from the field came in, other changes, notably to the seals, were made.

The 360 was Chrysler's highest performance V8 once the B-series engines were dropped; it was used in patrol cars and the Volare Roadrunner and Kit Car — but was dropped as a car engine in California at the end of the 1979 model year, and everywhere else at the close of the 1980 model year (in production terms, at the end of March 1980). From this point on, the 360 would continue solely as a truck engine. There weren’t many buyers for the car 360 and fuel economy was too low. 360 production moved to a new plant in Saltillo, Mexico.

To see how much of a fuel-economy hit owners could take by switching from the 318 to the 360, we can look at some 1984 EPA figures—the first year in the EPA database. Fuel economy is based on tests taken at that time, and have not been adjusted to try to “guestimate” how they would be according to the much tougher testing regimen used today. Figures shown are for automatic transmissions with the most favorable axle ratios. The Cordoba was listed for 1984, but was not actually made in that model-year.

| City/Highway mpg | 318 | 360 |

|---|---|---|

| Ramcharger RWD | 13/19 | 12/16 |

| Ramcharger 4x4 | 13/17 | 11/15 |

| B150 Van (RWD) | 14/18 | 12/16 |

| D250 Pickup | 14/19 | 12/17 |

| Chrysler Cordoba | 17/25 | n/a |

According to the EPA, at least, the 360 took a hefty 2-3 mpg toll on highway mileage, and a 1-2 mpg toll on city mileage—all else being equal.

For 1987, the truck versions of the 318 and 360 gained roller tappets, two years after the passenger-car 318s were switched over, according to Willem Weertman. Perhaps responding to customer pressure, the company now had two versions of the 318 for passenger cars, one taking premium and one taking regular—according to the EPA’s records. The regular-fuel engine was probably not available to retail buyers, but was aimed at fleets (taxis, city police cars, and so on). There was also a truck 3.9 V6, essentially a 318 with two cylinders removed.

Chrysler had planned to fuel-inject the passenger-car 318 for the 1987 Chrysler Fifth Avenue, Dodge Diplomat, and Plymouth Gran Fury; some believe they did not because, in 1986, the company decided to end production of the aging rear-drive fleet. Purchasing AMC gave them more options and in 1987, Chrysler moved M-body production to Kenosha, keeping the cars in production into the 1989 model year—but they never had fuel injection, which could have made the M-bodies more attractive to potential buyers. (Four-barrel police versions of the 318, incidentally, still had the old flat tappets—they were not brought up to date with hydraulic rollers.)

For 1988, Chrysler press releases show the Fifth Avenue as having either 147 hp and 256 lb-ft of torque, or 140 hp and 265 lb-ft of torque—the former set of numbers from a summary page and the latter from the Fifth Avenue’s specs. Fuel economy was rated at 17/23 in the 3,760-lb car.

Truck versions of the 318 and 360 finally gained fuel injection with the 1988 model year, though some trucks still used a four-barrel Rochester Quadrajet carburetor into 1989. Chrysler used a throttle body system, with one injector per cylinder bank, rather than the one-per-cylinder setup that would become de rigeur in the early 1990s. That simpler system was cheaper (two injectors rather than eight), easier to engineer, and possibly more reliable because the lower pressures were less prone to fuel leaks. Throttle body injection was not the ideal but it gave owners dramatically better drivability, lower maintenance, and higher gas mileage—with more power. (The injectors themselves were sourced from Bosch, and used a solenoid-operated ball-in-seat system to regulate fuel flow; when the computer demanded fuel flow, power was applied to the solenoid and the ball was pulled up, letting fuel flow. The spray came out across a 45° sweep.)

Other changes were made at the same time to take advantage of the fuel injection. The engineers started using swirl intake ports to mix the air/fuel better; since the system had taller lifters which changed the pushrod angle, the pushrod guide holes had to be enlarged, and the pushrods were shortened and reduced in diameter. The company claimed that they increased throttle area by 32.5%.

The fuel-injected 318 had more power than the four-barrel version, with 170 hp and 260 lb-ft of torque (some sources claim 280 lb-ft but press releases show 260; in the 1991 Dodge Dakota, due to air path restrictions, it may have produced 165 hp and 255 lb-ft - that is what the press releases said, though the brochure had the 170/260 figures). The 360’s output rose sharply as well, to 190 hp and 292 lb-ft of torque.

The main change at this point was the use of more durable valve stem seals in the 1990 models, which also had “lifetime” exhaust systems using 11% chromium steel alloy on all pipes, the muffler, welded-on hangers, and the catalytic converter housing. This year also had a single-board engine controller replacing the two-board controller; mounted in the engine bay, it was designed to be cooled by airflow while the truck was moving.

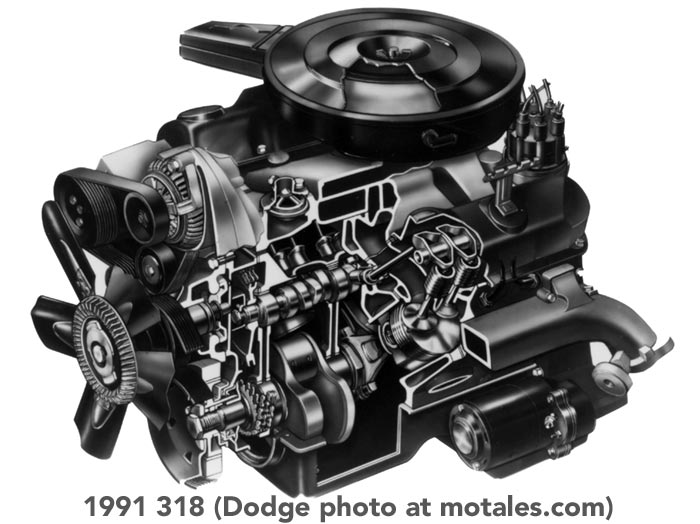

In 1991, just before the Magnum version, the 318 was rated at 170 hp and 260 lb-ft of torque, with a 9.2:1 compression ratio; the 360 was rated at 190 hp and 292 lb-ft, with an 8.1:1 compression ratio. The 318 was available on pickups and most B-vans; the 360 on full-sized pickups and B-vans other than the B-150. The 1991 press book shows a second 360 V8 for vans, with 8.1 compression, rated at 205 hp and 305 lb-ft, without any explanation.

The next major change was a rather hefty one, creating “Magnum” engines which lasted into the next century. The 318 was converted over for the 1992 trucks, and the 360 for the 1993s. Changes included sequential fuel injection, with each cylinder getting its own injector; a new throttle body and tuned plenum-ram intake manifold; redesigned heads and valve covers; lower restriction exhaust manifolds; and pedestal-mounted rocker arms. As a result, power shot up quite a bit—to 230 hp for both engines, with torque at 280 lb-ft for the 318 and 325 lb-ft for the 360. The 318 was now fit for the Jeep Grand Cherokee as well as an all-new and far more attractive series of Ram pickups... but that is another story.

LA engines had an exhaust crossover in the intake manifold to warm the carburetor base; it tends to get clogged over time.

Timing marks are on the driver’s side of the timing chain cover; they can be blocked from sight by extra brackets on the bottom of the timing chain cover.

The LA V8 engines had two interesting spinoffs, one much more successful than the other: a V6 and a V10. The V6 was created largely by removing two cylinders, so the engine would fit in the new Dodge Dakota; but it also replaced the slant six in pickups. This engine was fairly rough (especially in the one year it used a carburetor), since it still had the V8’s V-angle, but with an automatic transmission it was acceptable. The V10 is better known; originally set at 488 cubic inches, it was based on the 360 but with two added cylinders. Both the firing timing and angle were off, but enthusiasts loved the V10 in both its versions—an iron-block truck engine with immense torque, set up as a cheap alternative to a diesel, and an aluminum-block engine with immense horsepower and torque, used in the Viper almost exclusively. But these LA-based engines are other stories.

| 1974 | 318 | 360 4-bbl |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel pressure | 5-7 psi | 5-7 psi |

| Idle speed | 750 | 850 |

| Air:Fuel | 14.3:1 | 14.3:1 |

| Bore | 3.91 | 4.00 |

| Stroke | 3.31 | 3.58 |

| Chamber vol. | 86.2 cc | 99.95 cc |

| Compression | 8.6:1 | 8.4:1 |

| Plugs | N-14Y | N-13Y |

| Piston weight | 20.9 oz | 20.6 oz |

| Duster weight* | 3,155 | 3,395 |

| Carb | Carter BBD | Carter ThermoQuad |

| Timing | TDC | 5° BTC* |

| 1971 Cam | 240-248-26 | 252-256-32 L.P. 268-276-44 H.P. |

* In pounds. Curb weight, which was 80 lb greater than shipping weight since it included needed fluids. Timing: 2.5° BTC for manual transmission cars with California emissions.

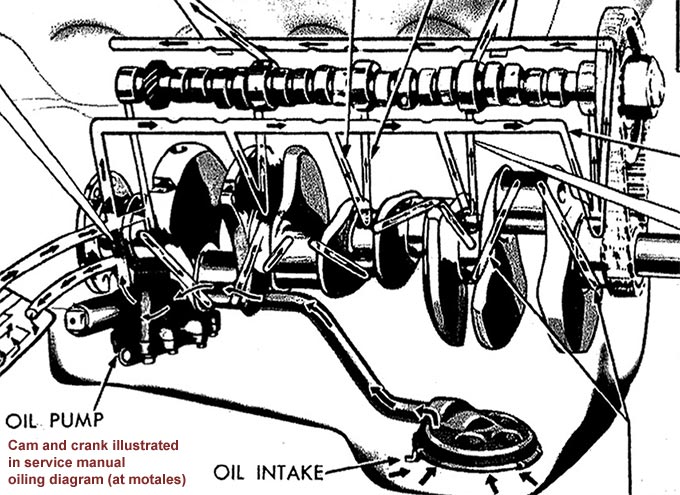

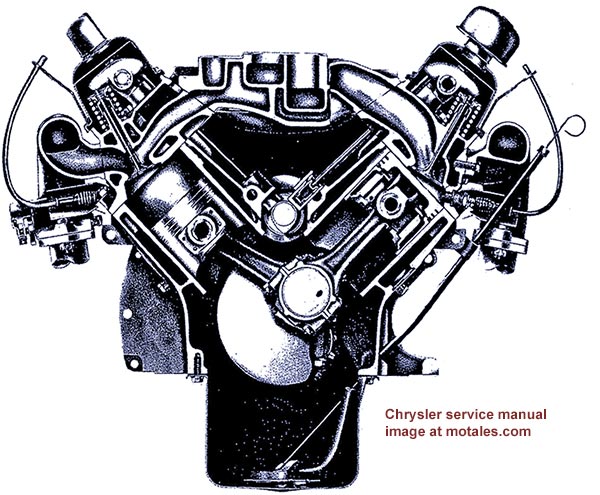

The LA engines in this era had cast iron blocks and heads, with no cylinder sleeves. Bore spacing was 4.46 inches. The engine was installed at a 3° angle, rear to front. Pistons were tin-plated aluminum alloy, with steel struts. Crankshafts were cast ductile iron at this time; the cam was also cast iron, and also drove the oil pump and distributor. The timing chain was made of sintered iron (“Super Oilite”), with nylon-coated aluminum sprockets to make it quieter. The 318 and 360 shared a timing chain.

Firing order was 1-8-4-3-6-5-7-2. Odd cylinders were in the left (driver’s-side) bank, even ones in the right bank; numbering started in front and moved to the rear. Mechanical fuel pumps were in the front of the engine, on the passenger side, supplying pressure of 5-7 psi. One plastic gas filter was in the tank, and a replaceable paper filter (in a metal or plastic container) was in the supply line. Carburetors had automatic chokes with electric assists; air filters had paper elements. By this time all Chrysler engines had pressurized cooling systems driven by a centrifugal water pump (in turn driven by a fan belt), with a coolant recovery bottle. For 1974, the thermostat was set to open at 195°.

Lubrication was pressured to 45-65 psi when the engine was at 2,000 rpm, using a rotary pump powered by the engine; it used full-flow filters which were replaced completely. The engines took four quarts plus one for the filter. Recommended oil grades depended on temperatures, and ranged from 5W-20 to 20W-50—even SAE 10 and SAE 30 were in the list. 10W-40 could be used in temperatures which sometimes dipped below –10°F but were usually above freezing. The main bearing, cam bearings, rods, and tappets all had pressure lubrication; the timing chain and cylinder walls had jet lubrication.

Spark plug gap was 0.035 inches; resistor threads were recommended. Chrysler usually used Champion plugs, long after dropping their own home-grown line. Cars and light truck engines used a 14mm thread, while heavier-duty truck engines used an 18mm thread. Electronic ignition was standard on all Chrysler cars starting with the 1973 model year.

Some of the following information might not be completely accurate, aside from valve sizes.

| Engine | Heads | Intake | Exhaust |

|---|---|---|---|

| 273 | 1.78 | 1.50 | |

| 318 | 1.78 | 1.50 | |

| 340 | X | 2.02 | 1.60 |

| 340 | J | 2.02 | 1.88 |

| 340 | 1972+ | 1.92 | 1.88 |

| 360 | All | 1.88 | 1.60 |

(Stephen Havens provided these to Allpar)

| Engine | Type | Lifters | Lift | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 273 | 2V thru 67 | Mech |

395/405 | 240/240 |

| 273 | 2V 1968-69 | Hyd | 373/400 | 240/248 |

| 273 | 4V thru 67 | Mech | 415/425 | 248/248 |

| 318 | 2V 1967 | Hyd | 390/390 | 244/244 |

| 318 | 2V 1968-88 | Hyd | 373/400 | 240/248 |

| 318 | 4V | Hyd | 430/444 | 268/276 |

| 318 | roller cam | Hyd | 391/391 | 240/240 |

| 340 | 4V 1968 man | Hyd | 444/453 | 276/284 |

| 340 | 4V | Hyd | 430/444 | 268/276 |

| 340 | 3x2V | Hyd | 430/444 | 268/276 |

| 360 | 2V 71-74 | Hyd | 410/412 | 252/256 |

| 360 | 2V 1975-end | Hyd | 410/410 | 252/252 |

| 360 | 4V | Hyd | 430/444 | 268/276 |

Pete Kranz wrote: “The only real problems with the LA engines were valve stem seals that would shrivel up, resulting in burning oil. The old-fashioned two piece rear main ‘rope’ seals were easier to replace, but leaked like a sieve. Nylon-coated single row timing chains and sprockets could shed their teeth and plug up the oil tube pickup screen.”

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky