The first Chrysler car was created mainly by Zeder, Skelton, and Breer (ZSB), three skilled engineers who set out the basic lines of the engine, chassis, and just about everything else. They worked together, coordinating on a personal level, getting expertise in every part of the company together by funneling it to three close friends. This helped them to build the world’s first truly modern car, the Airflow—the first car whose body was dictated by science, not coachbuilding.

Zeder, Skelton, and Breer left the company in 1949-51. The split of Engineering into silos of knowledge was almost complete as they stepped out of power and the functional org-chart separations took over. The engine designers still worked as a small team, but increasingly each group was isolated from the others. The idea behind specialization was to create in-depth expertise, but as people stayed in their own niches, it seemed that Chrysler stopped being quite as technologically advanced.

Specialization was so strong that one engineer did nothing but adapt axles to whatever size and strength was needed. Every part of the car ended up in a different group by the late 1950s, including testing. When each design was done, it was sent to the draftsmen and then to next group, and Parts and Manufacturing had to make it all work. Zeder, Skelton, and Breer were no longer around to coordinate it all and bring everyone together.

Then, in 1957, Chrysler created a skunkworks—a cross-functional team, bringing people from different areas of expertise together into a small space with a nearly impossible budget and deadline. (The term “platform team” came later, because they’d work on a single platform which could spawn multiple cars. The reason for platforms was the expense of designing a unibody chassis and creating the stamps for it.)

The reason the skunkworks was created was because senior management decided that their new compact car would be done directly by Development-Design, rather than starting it with Advance Engineering and then moving it on. The head of Development-Design was Otto Winkleman, who had worked with Alexander Griswald (“Gid”) Herreshoff, one of Carl Breer’s key assistants.

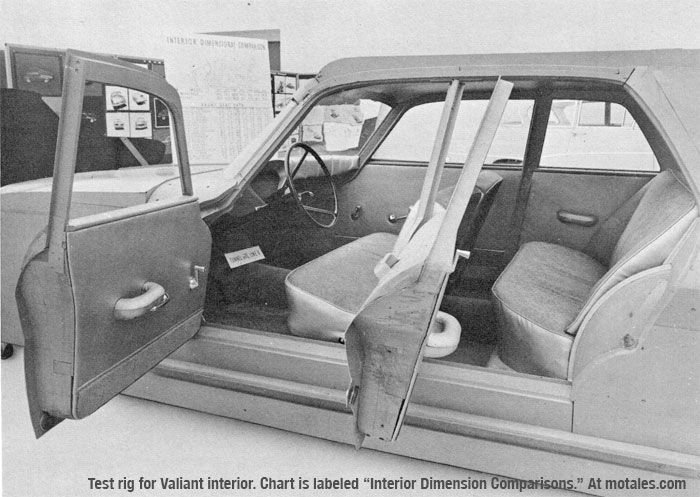

The Highland Park headquarters didn’t have room for the design team, so they leased a building on nearby Midland Avenue, moving engineers there as needed. People from different specialties worked together, instead of on different floors or in other buildings; working together made a big difference. People could overhear conversations and say, “I have a solution for that.” More often, they could ask someone in the same room for help, not having to go to their boss for permission to issue a formal request. Supervisor of chassis design Al Bosley called communication even between different parts of chassis engineering “tenuous and difficult.” He said that “One five-minute discussion at Midland Avenue could have taken weeks in Central Engineering.”

They even had a staffer from Materials Engineering assigned to the building after a while; instead of sending drawings out to get metals assigned, which could take weeks, they could just hand them over and talk about what each one wanted. That meant a much more rapid pace, with better results, than the usual “toss it over the fence” system which had no feedback.

Bob Sinclair ran the team, mainly working the background to move obstacles out of the way and get resources. Engineers worked under high pressure—Al Bosley said “from six or seven am, sometimes to six or eight o’clock at night… Saturday, we ran from eight to one. That was every week, so it was a fairly intense activity.”

High pressure, small team packed in tightly, a leader deflecting obstacles (including other executives)—it all added up to a class skunkworks.

The new compact car, Valiant, took a much higher than expected share of its class in North America, and was Chrysler’s only domestic car to sell in volume in Europe, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. New brake, axle, and front suspension designs replaced the older versions on the company’s entire lineup. The team had been an astounding success. Still, Bob Sinclair never used the method again—and neither did Chrysler, until after 1987.

At that point, Chrysler acquired AMC and put its chief of engineering in charge of Chrysler Engineering as well. Francois Castaing, a former racer used to small cross-functional teams (because AMC wasn’t large enough to have silos), wanted to convert all of Chrysler to AMC's method, calling the cross-functional groups “platform teams.”

The 1990s “platform teams,” based almost entirely on AMC’s setup, kept the various functional groups such as Powertrain, but evaluations, raises, and next assignments came from their team supervisor, and their primary work was done as part of a cross-functional, product-focused team. This brought better communication and give-and-take as new cars were developed; certainly there was more innovation as people worked together and were able to enact small changes with big benefits. If an engineer or designer had a good idea, others would work together to make it happen, quickly rerouting equipment or making other changes to get it done. Castaing ran loose budgets, as well, so money needed in one place could be taken from another.

As the 1990s progressed and Chrysler came out with groundbreaking new cars over and over, spending less to develop them in dollars and in years, the advantages of the new approach became quite clear. Development was radically faster, because there was little waiting on otehr departments, and because there was a greater spirit of cooperation and helping where one can. It had been the same when making the Valiant. Certainly, the 1990s were good to Chrysler: they went from making a profit only on Jeeps and minivans, to having profitable large cars, midsize cars, compact cars, and pickups. The company's pickup market volume quickly tripled. The new engineering headquarters, accordingly, was built to make it easier for the cross-functional product teams—the platform teams—by concentrating people into the same place.

The teams did have disadvantages. It required more people to do the same work, increasing payroll costs, and there was some “reinvention of the wheel” as different groups found different ways to do the same thing. Interiors tended to have different user interfaces, though having a single person controlling suspension feel helped. Teams with leadership issues did not work as well; the second-generation Neon team has serious issues when its leader died unexpectedly.

Retired Chrysler and AMC engineer Bob Sheaves wrote that platform teams used people in different roles at once (updating current models, working on a new car, selecting and verifying suppliers, and testing parts. “Let one thing go bad, and the whole process tumbles like the proverbial house of cards.”

Al Bosley, in 2017, argued that one reason cross-functional teams are not used all the time is because specialization really does increase the depth of a company’s expertise. General Motors had cross-functional teams for many years, but also kept an applied research group and central engineering staff with a powertrain team, electronics team, test team, and so forth. At Chrysler they were all brought into developing cars, and their talent ended up scattered.

One solution, not yet tried, is to only use crossfunctional teams every two or three generations, leaving refreshes and such to traditional groups. Even Francois Castaing, who brought the method back to Chrysler, saw its limits. He said at the time, “ Bringing the platform concept on board was a leap forward ... but from now on we will focus on continual improvement. I don't see another revolution around the corner. I see continuous evolution of what we have done, the way we're operating.”

One interesting aspect of both the Valiant and the 1990s Chrysler teams was how they excited and engaged the engineers. Al Bosley pointed out that a surprising number of Valiant people ended up in leadership—including Bosley himself, who retired as a vice president. Castaing observed, “I know of many in engineering who, just three years ago, were conservative, anti-risk taking, and planning a future to eventually move out of Engineering into Product Planning or Finance. ... [Today] They want to stay in the business of engineering cars. They stand behind their decisions, no hiding... good or bad.”

Only the original 1960 Valiant was designed by a cross-platform team. This car won the first five places in the first-and-only NASCAR compact car race, and made Chrysler relevant around the world again. Chrysler sold 146,792 Valiants in their first year, and had to reassign the new car to Plymouth. Valiant broke 200,000 sales in 1963, and, with the Duster, reached a peak of around 475,000 in 1974 (alongside a quarter of a million similar Darts. Likewise, the first new car developed in this method under Castaing, the Viper, seemed to make Chrysler relevant again—and brought the company back to win Le Mans championships against much better-supported cars. Every time Chrysler used the system, they had tremendous success.

Could Stellantis bring back the skunkworks approach, bringing everyone into one physical place instead of leaving them scattered around the world? Quite probably, though it would be a very different method than was used to create the Valiant or Airflow or 1924 B-70. Auburn Hills has reportedly been too hollowed-out for a complete team to make a single car, but if there are enough people left there, the ideal would be to rearrange office space so a team could work together, growing as the project gathered speed (as the Viper, LH, Neon, and other new car teams grew). Otherwise, with help from experts, a team could be forged through the current online systems—it would be tougher, but it could be done. It would require an executive such as Tim Kuniskis to push his ego aside and work as a guardian rather than as a guide, protecting the team from the rest of the company.

Citroën uses this kind of team for advanced design work. Ford used it for their “Model T moment,” bringing out eight low-cost electric cars, starting at $30,000, announced in August 2025.

Will Stellantis join them? Only Antonio Filosa will tell. The company is in dire need; whether its executives recognize that and know the solution, is what matters.

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky