Chrysler put hemispherical-head combustion chambers into its first V8 engines, released for the 1951 cars; years of testing had shown that was the most efficient design, but that efficiency came at a high cost—slow and costly production, heavy weight, and bulky valvetrains. The company simplified the hemi to a “poly,” then turned to cheaper, faster-to-make, and more compact “wedge” heads.

The second generation “Hemi” design took engines designed to use wedge heads and adapted them to hemispherical-chamber heads. These 426 cubic inch engines were created solely for racing, but Chrysler had to release street-legal versions so “stock car” racers could keep using them. They were an impressive 425 bhp “gross,” without the alternator, water pump, oil pump, etc.—which translated to a still-impressive-for-the-time 350 hp net (with all those accessories, as it would be driven, and measured at the crank).

In the 21st century, Chrysler returned to hemispherical heads as they replaced the venerable wedge-head 5.9 (360) V8 with a smaller 5.7 liter Hemi that created far more power. That design was quickly transformed into a 425-hp 6.1 liter V8 that outpowered the old 426 Hemi—and then a 6.4 liter (392 cubic inch) V8 made in two forms, a high-performance version for cars and a high-durability version for trucks. The high-performance version produced 485 hp and 485 lb-ft of torque—over 100 hp more than the fabled 426 Hemi had produced in street-legal form.

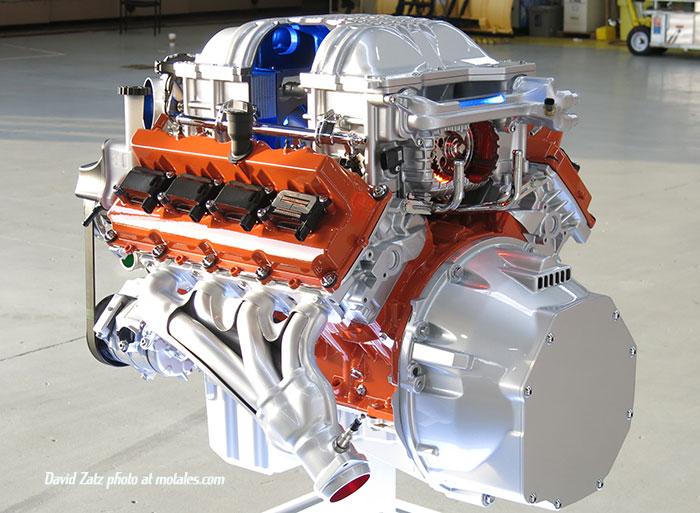

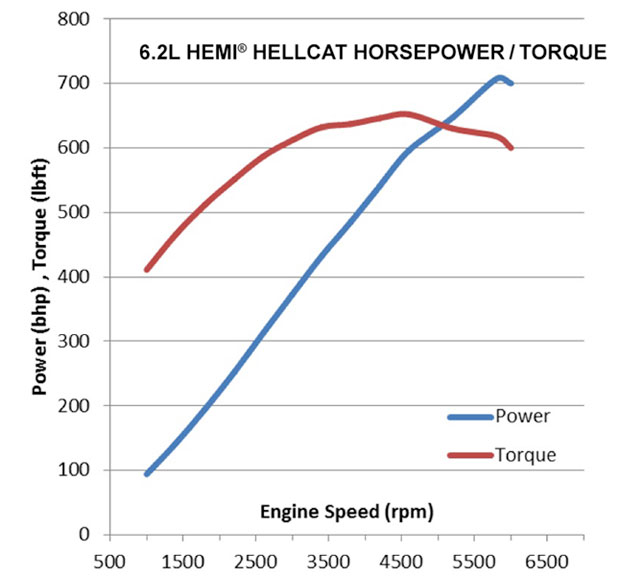

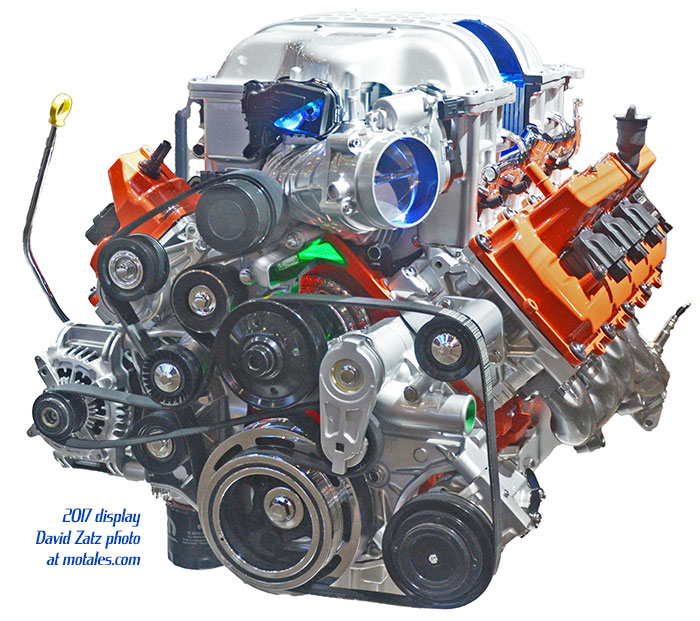

Wanting more, Dodge worked on a supercharged engine coded “Hellcat,” after the World War II fighter plane. Chrysler didn’t use its code names in public, as a rule, but the Hellcat name was promoted relentlessly as the engine’s 707 horsepower shocked the automotive world. That was well above the highest-performing V10 Viper engine—and more than double the net output of the legendary 426 “Street Hemi.”

Chris Cowland, Director of SRT Powertrain, described the Hellcat engine in 2014. Some high points of his presentation were:

Chris Cowland, who hails from Britain, spent 13 years at engine-maker Perkins, and worked at Lotus, Ricardo, and AVL. He reached Chrysler in 2008 and was made Chief Engineer and Platform Director for the Pentastar V6.

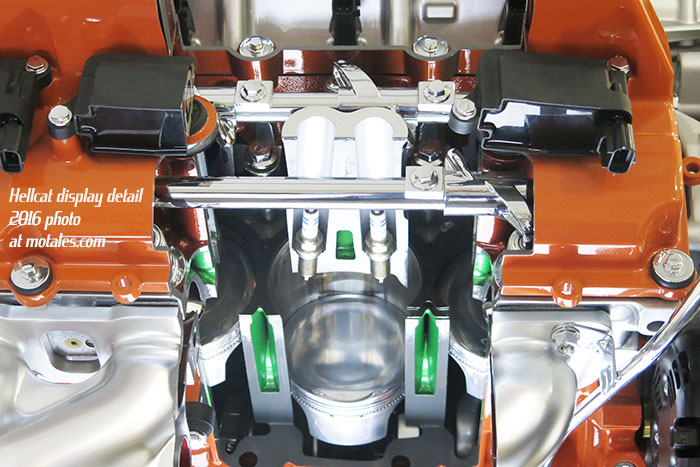

The block, heads, and covers were all powder-coated to a glossy orange. The pistons had a 32.48mm compression ring height and 6mm top ring (versus the 6.4’s 30.35mm compression ring height and 3.75mm top ring); by intent, they weighed the same as those in the 6.4 “Apache” (SRT 392).

| Part | Material |

|---|---|

| Rods | Powder forged |

| Wrist pins | DLC coated |

| Crank | Forged steel alloy (counterweighted) |

| Pistons | Forged aluminum |

| Bearings | Induction-hardened surfaces |

| Heads | Aluminum alloy (A356) |

| Block | Cast iron |

| Valve covers | Die-cast aluminum |

The connecting rods had tapered small ends to make room for wider (24mm) wrist pins. The engine was designed to withstand firing pressures of 110 bar.

As with all modern Hemi V8s, the engine has two spark plugs for each cylinder, an idea credited to a man who cut his teeth on the original Chrysler V8—Willem Weertman, retired head of engine development. The twin plugs help solve otherwise impossible emissions issues.

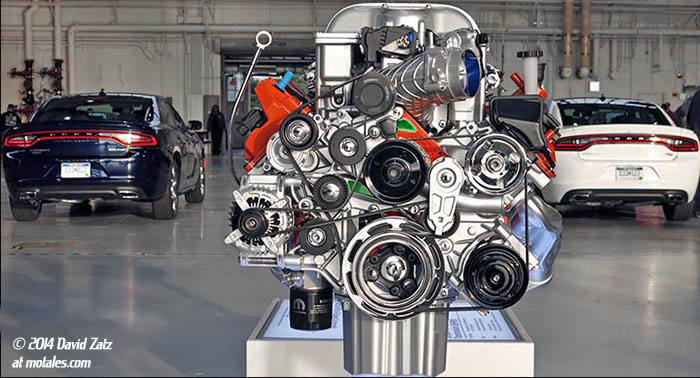

The crank damper had a separate 10-rib poly-V drive for the supercharger, and diamond-coated washers for torque drive. Keeping the accessory drive on the nose of the crankshaft was difficult; it required the special washer to increase friction and provide enough torque for the supercharger. The drive pulley and crankshaft nose were not tapered. The company chose a supercharger, rather than a turbocharger, because it builds power right off idle rather than coming into play once the exhaust spins a turbine.

The heads, with two plugs per cylinder, were treated to resist heat and increase strength. The intake valves had hollow stem inlets and measured 54.3mm; the 42.0mm exhaust valves were sodium-cooled, with temperature resistance of a continous 800°C. (These were actually smaller than the 426 Hemi’s 57mm and 49mm valves.)

Valves and ports were typical conventional for the Hemi design; spray injectors (one per cylinder) were bent to 20° get the right angle and had a 17° cone. Combustion was analyzed by computer during development. Fuel lines had to be half an inch in diameter, because the injectors could flow 0.63 l/minute from the variable pressure fuel pump in the tank (which could drain the tank in 13 minutes at full tilt). One interesting design choice was directing the fuel to hit the back face of the inlet valve, getting an almost continous flow at high revs, to cool the valve.

The crankshaft used the same forging process as the 392, but was machined to reduce peak cylinder pressures since the supercharger fills the pistons instead. The cam profiles had a 14.25mm/ 278° inlet and 14.0mm / 304° exhaust lift—but the variable valve timing had 37° of phasing authority. There was no cylinder deactivation system.

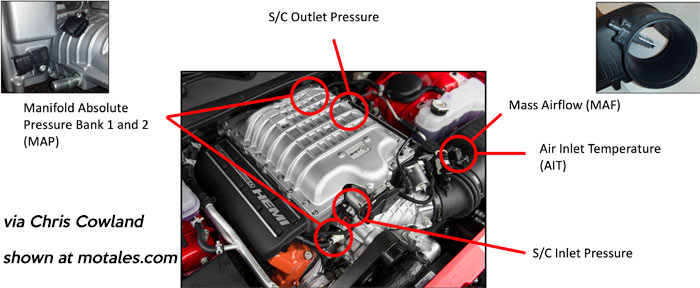

The intake system used Chrysler’s largest-ever throttle body, with a 92mm diameter and a patented twin-inlet airbox; one inlet came in through the front marker light when the Hellcat was installed in the Dodge Challenger. The airbox held 8 liters of air. The computer used airflow measurements from a pair of manifold pressure (MAP) sensors, one in each cylinder bank, for basic engine control strategy; OBD and other functions used a mass airflow (MAF) sensor.

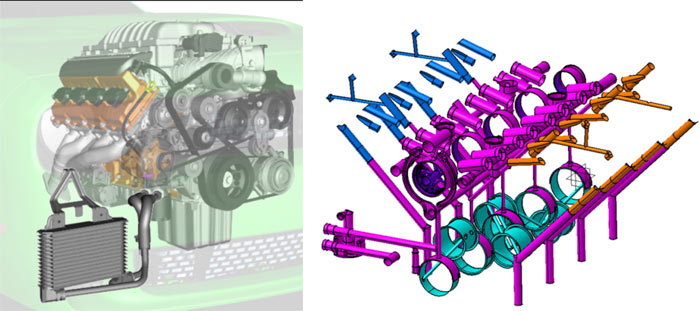

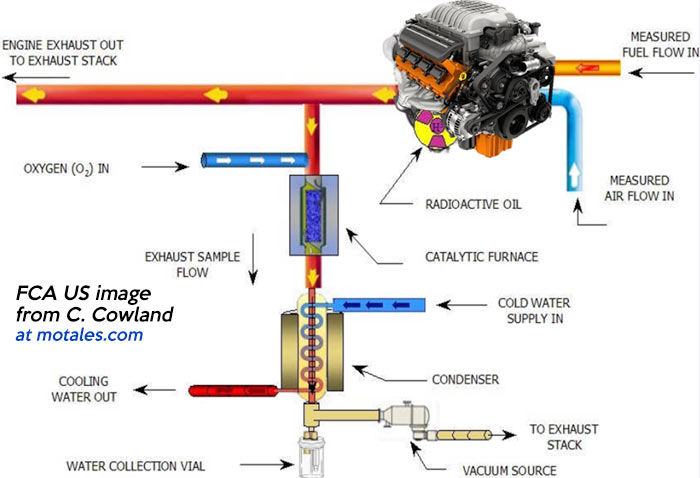

Oil use was optimized using radioactive Tritium tracer technology—production cars didn’t have radioactivity as shown above

The IHI massive 2.4 liter (2380 cc) twin-screw IHI supercharger was driven by a 10-rib poly-V belt drive from the crank damper; it could handle 80 hp, giving some indication of how much power the supercharger can use. Air came into the unit, was compressed, cooled through twin air/coolant heat exchangers, and sent down runners to a 180° turn, then going through one of four heat exchangers, and then into the intake valves.

The supercharger was engineered specifically for this engine, and includes an electronic bypass valve to regulate boost pressure up to 11.6 psi. It was developed using fluid dynamics analysis and tested for 300 hours at full load with variable speeds and 300 hours at 14,160 rpm with a 1.5 pressure ratio. Special rigs had to be made to test for noise and vibration. The cooling system overall was good enough that the engine does not need to hold back on power due to cooling demands, unlike many competing engines.

A one-way clutch decoupler reduced gear noise when belt loads were lower. The supercharger had its own cooling circuit which included a 250W electric coolant pump (the external cooling system was created by Chrysler, while the integral air coolers were created by IHI). The engine as a whole went through severe thermal shock testing, which included adding cold coolant repeatedly to hot engines to stress the gaskets and metals.

The supercharger was lubricated with synthetic oil sealed into the unit; to assure lubrication, it was also tested at a 47° incline. The drive ratio was 2.36:1; the supercharger could reach 14,600 rpm.

A huge amount of power means a lot of exhaust; the Hellcat team created special double-walled exhaust manifolds which could stand the heat. The 73mm diameter dual exhaust system only created 58 kPa of back pressure at 610 g/s. The catalyst was a high-flow, close-coupled ceramic setup capable of working at 1050°C and 600 cpsi. The exhaust sound used control valves to accentuate full-throttle noise.

Lubrication was provided by 0W40 synthetic oil specially developed for SRT. The windage tray provided consistent oil delivery under high acceleration and high cornering alike. An air/oil heat exchanger up front kept the oil cool during extreme conditions. A 25ml/rev gerotor pump was drive from the nose of the crank; each piston had a cooling jet with a check valves. The company analyzed lubrication using radioactive trace materials.

To develop the Hellcat did not just require time and computers. The company’s test facilities had to be upgraded with no dynonometers, upgraded air handling in the test cells, and fuel conditioning and measurement equipment that matched the Hellcat’s high output. New tests were created to prove the durability of the engine under track driving, including a 24-hour continuous race pace with sustained high speeds, high ambient air temperatures, and no fewer than one hundred consecutive drag starts; the system was even tested for its reactions to deep thermal shock.

| Spec | Measure |

| Bore x Stroke | 4.09 x 3.58 in. (103.9 x 90.9 mm) |

| Compression | 9.5:1 |

| Max power | 707 hp @ 6,000 rpm |

| Torque | 650 lb-ft @ 4,800 rpm |

| Fuel | 91 octane (premium) |

| Oil | 7.5 quarts 0W-40 synthetic |

| Coolant | 14 quarts |

The blocks were purchased from a vendor and machined on the company’s Hemi production line at Saltillo, Mexico. Extra production line stations were added to check the engines more carefully as they progressed, and every engine was dyno-tested under load for 42 minutes at up to 5200 rpm and 90% load before being shipped to the vehicle plants.

The Hellcat is an incredible system: its emissions are a tiny fraction of those of the original Dodge Challenger, and fuel economy is at least double that of a 1978 car with a 440 V8. Overall, the Hellcat nearly doubles the legendary 426 Hemi’s power.

Grumman made 12,200 Hellcat fighter planes in a little over two years. The planes destroyed 5,223 enemy aircraft, more than any other Allied naval planes, with an overall kill-to-loss ratio of around 19:1. (That was greater than the best Japanese aircraft by 4:1). Only 270 were downed by aerial combat during the war, mostly falling to training accidents or transportation issues.

The engineers pulled out the stops for the 2018 Dodge Challenger SRT Demon, certified by the Guinness Book of World Records as the first production road car to lift the front wheels on a hard launch. The Hemi had the same dimensions but pushed out 808 horsepower and 717 lb-ft of torque on premium fuel (91 octane)—or 840 horsepower at 6,300rpm and 770 lb-ft of torque on racing fuel (100 octane). Only three cars in the word had more power when it was launched—a Ferraris, a McLaren, and a Porsche. With this engine, the Challenger did zero to sixty in 2.3 seconds (2.1 with rollout). Zero to 100 came up in 5.1 seconds, with a 9.65 NHRA-certified quarter mile, the fastest for any production road car in the world (beating the Bugatti Veyron).

To get there, the 2.4 liter supercharger was replaced by a 2.7 liter model; and boost was raised from 11 pounds to roughly 14.5 psi when running on the 100+ octane race gas. The internal parts and cooling system had to be strengthened to take the load—as did the transmission and tires.

A typical Hellcat started with around 100 lb-ft of torque off idle, with little boost. The Demon could launch with 8.3 pounds of boost and 534 lb-ft of torque, creating 1.8g of acceleration force—thanks largely to the Torque Reserve anti-lag system. Such systems have been used by racers, but were never before built into a production car. Torque Reserve closed the supercharger bypass valve to build pressure quickly, and briefly deactivated alternating cylinders to spin the engine more quickly while revving before a launch. That let the Demon launch at a higher engine speed and higher boost level.

Dodge built in an electric cooling system, using the intercooler loop, to deal with heat after the engine shut off, which helped for between-race cooling. The After-Run Chiller was controlled and monitored from the telematics screens.

The power caused an NHRA ban on the stock Demon, the first stock car to be banned from competition in stock form; owners have to add a roll cage to race it. It came with a stronger driveshaft and axles for durability on the strip. The crank pulley was also reinforced. The various steps to increase durability gave Dodge the confidence to warrant it for three years or 36,000 miles, bumper to bumper, and five years or 60,000 miles for the powertrain (but any aftermarket changes voided the warranty).

Like the Hellcat, the Demon has the driver’s side “Air Catcher” headlight, but it also has the Air Catcher treatment on the passenger’s side assembly – like the new Challenger T/A, and unlike the current Hellcat.

The Demon’s hood scoop measured 45.2 square inches; it sent air through a path built into the hood to a large air filter box. This new Air Grabber hood avoided the intake of any warm air from under the hood.

The Dodge Demon broke through the 800-hp barrier; the engineers learned enough from its development to increase the Hellcat’s power to 797 (and then 807) hp. The Charger and Challenger with this engine needed special wheels and fender flares to handle the power, and were set apart by the name “Redeye.”

The original Challenger Hellcat had an air box that drew air through one of the front light holes and from in front of the wheel; the hood scoop fed air into the engine bay, not the engine. The 2019-23 Challenger Redeye (797 horsepower) and Super Stock debuted a dual-snorkel hood which fed directly into the engine, but could still draw air from the headlight and wheel-well; and it had a conical filter for 72% more flow, and an even bigger 14.8 liter airbox. The Charger Redeye had a single scoop, but it too fed directly into the airbox. Finally, the Redeye had a wider tube into the air cleaner, increasing airflow by 25%. (The “normal” 2019-23 Challenger Hellcat adopted most of the new induction setup—other than the airbox, conical filter, and wider tube—adding ten horsepower in the Charger and Challenger).

The supercharger went from 2.4 to 2.7 liters by increasing the length of the rotors by 28mm; it had higher boost pressure, going from 11.6 to 14.5 psi, partly by raising the top internal speed to 15,340 rpm. A new front bearing plate smoothed air flow and added some air cooling.

The Redeye used the same fuel injectors as the Demon and Super Stock Hellcat, with a twin fuel pump arrangement (both in the tank) that increased peak pressure by 27%. Peak fuel flow rose up to 1.36 gallons per minute (a modern showerhead is around 2.5 gallons/minute). The heads had the same materials and processes, with a 34.5° valve angle, but the collets, valve springs, and spring retainers were all changed, and oil cooling at the tips of the rocker arms increased.

The new cam profile used an intake lift of 14.25mm and exhaust lift of 14mm. Lobe centers were at 109° and 137°; durations were 224° and 240° at 0.05 inches of lift. The variable valve timing had 17° of total variation.

The red-painted engine blocks were made of high-strength cast iron; the deck plate was honed to reduce bore distortion at high revs. The main bearing cap had a 47% greater cylinder head clamp load. The crankshaft was rebalanced and crank bearing surfaces were induction-hardened, with each journal having individually optimized main bearing clearances; the same engine could see differences of up to 10 microns. The pistons added an inclined inner box wall for strength; oil cooling was increased with jets in each cylinder. The rods were upgraded for over 200,000 psi of internal pressure.

The exhaust went through dual-wall tubular stainless steel headers, then close-coupled catalytic convertors, and finally a dual exhaust system with a 73mm diameter. Cooling was similar to prior Hellcats; Redeye and Super Stock also had the Demon’s SRT Chiller, which diverted cold air from the air conditioner to the intercooler.

The Redeye was similar to the Demon in many ways, but calibrated for minimum 91 octane fuel instead of the Demon’s 93; and the Redeye lacked the Demon’s racing-fuel calibration which allowed for 840 hp. Visually, the Hellcat had orange valve covers; the Demon had red ones; and the Redeye and Super Stock had black ones.

If you missed our deep dive on how the Demon 170 engine differs from the supercharged Hemi in the 2018 Demon and current Redeye models, click here.

All Hellcat engines ceased production in 2023, survived by the 2024 5.7 and 6.4 liter Hemi V8s.

Books by MoTales writer David Zatz

Copyright © 2021-2024 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.