With its high-end trim and straight-six engine, the Hudson Hornet was an unlikely car to win NASCAR trophies; but a cleverly designed body, with a low center of gravity and good front/rear balance, made it a barnstormer around turns. Its straight-six was close to most existing eight-cylinders—indeed, it beat many of them. One could easily ask what American company would be so audacious as to make a hot, high-trim car powered by a mere six-cylinder; the answer was Hudson.

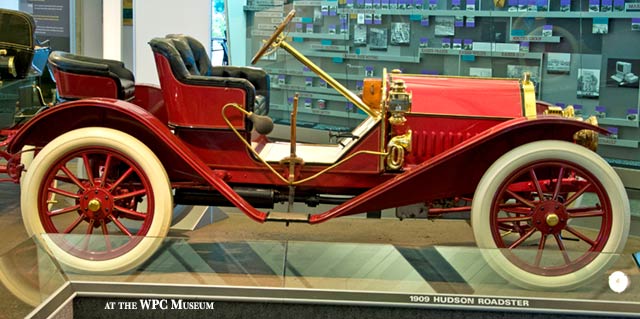

Hudson, named after its primary funder (Joseph Hudson, of the Detroit department store), was created in 1909; its cars were among the first to move the steering wheel to the left side, putting the shifter in the center. In 1916 they made their six-cylinders unusually smooth by using a balanced crankshaft, a competitive advantages for years afterwards.

Hudson, including its lower-level Essex line, did quite well through the Roaring Twenties, breaking 200,000 sales per year from 1925 to 1928 and notching over a quarter-million sales in 1929—but then its market was slammed by the Great Depression. Hudson dropped from being a major automaker to “the independents”—the many minor automakers who struggled against the massive GM and Ford.

Immediately after World War II, auto production restarted; automakers used their pre-war designs at first because they didn’t have time to set up new tooling, and the market was ready for any vehicles by then. Every automaker was also hard at work on a brand new design; Studebaker’s arrived for 1947, Packard and Cadillac for 1948, and Ford for 1949. They all had to choose between the tried-and-true body-on-frame, or something new; and they had to pick large, medium, or small, keeping in mind that steel rationing ended in 1945, but could restart to aid the Korean war effort.

Hudson’s immediate postwar sales were not especially strong—72,484 in 1946 and 83,344 in 1947. That may explain why Hudson bet on an innovative design, first released in the 1948 Hudson Super and Commodore. These were essentially the same car in different trim levels.

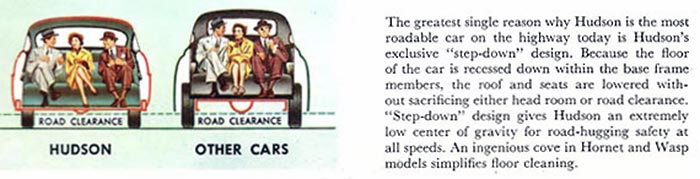

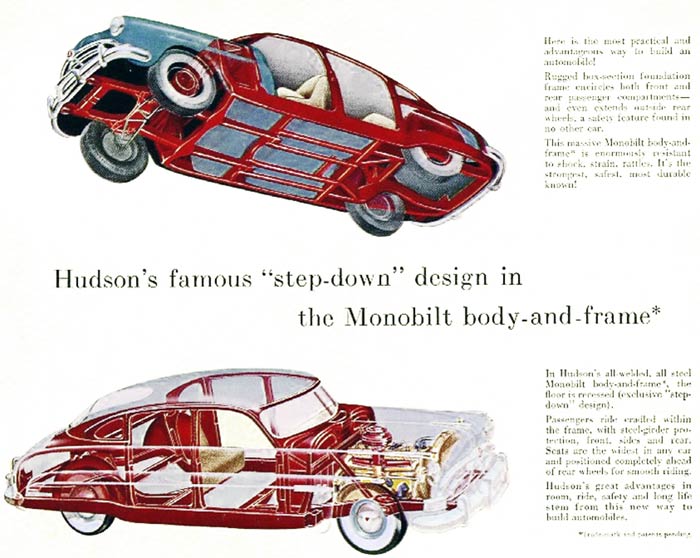

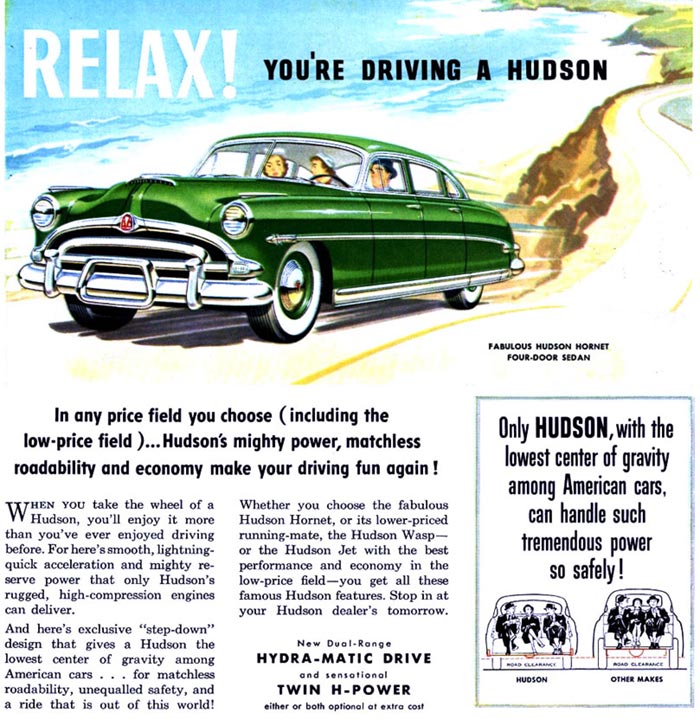

What set these cars apart was partly their unit-body construction, which was still quite unusual in American cars. The unibody made it stiffer and a bit lighter than many competitors. They were also engineered with a low engine position and floor pan (dubbed “step-down”), dropping the roof by about a foot, compared with direct competitors, without hurting headroom, which lowered the center of gravity, which made for better handling and ride. The downside was that it was harder and pricier to make numerous sizes and shapes from a unibody design than from a body-on-frame.

Head stylist Frank Spring said that the sleek looks were inspired by the P-38 Lightning fighter plane; the curvaceous cars had a long hood to allow for a straight-eight engine and “streamlined” curves. The new cars were a real hit by Hudson’s standards, with 1948 sales of 109,497—the best number since the crash of 1929 (Hudson’s peak year of all time, including sub-brands, was 1929, with a quarter-million sales). Hudson rose from #13 to #11 in the industry.

1949 sales grew as well, reaching 137,907. The 1950 Hudson line added a smaller car, the Pacemaker, at an even lower price; despite the new entry level car (or perhaps because of it), the company fell to #13 in American sales, at 134,219. The Pacemaker was popular in its launch year, with production of over 60,000; but 1951 production dropped to 34,495, and by 1952 the Pacemaker was barely visible on the assembly line.

Hudson made inline engines with six and eight cylinders. The top-range Commodore’s 1950 sales were split roughly 1.5:1 in favor of sixes, while the Super was around 17:1 in favor of sixes. They would not drop their eight cylinder engines until 1953, though the Super would soon be restricted to sixes, leaving the straight-eight as a Commodore option.

Chrysler, Dodge, DeSoto, and Plymouth still relied on six-cylinders; the first performance V8s were just starting to appear, with the Olds 88 the most likely candidate for “first” credit (the pre-war Ford V8, unless heavily modified, could be beaten by contemporary Plymouth sixes). Chrysler’s optimistically-named “Spitfire” 251 cubic inch six only had a single-barrel carburetor, rated at 116 bhp (gross), and that was the corporation’s top car engine for 1950. Chrysler’s first V8 was sold only in the 1951 Chrysler Saratoga, New Yorker, and Imperial, generating 180 brake horsepower from 331 cubic inches; the 1949-51 “Rocket” V8 in the 1949 Oldsmobile 88 generated 135 hp.

The stage was set for the most famous Hudson of all time, the 1951 Hudson Hornet.

The 1951 Hudsons were variants on the same basic car in two sizes. The Pacemaker was smaller; the Super, Commodore, and Hudson were differentiated by engine, trim level, and luxury features.

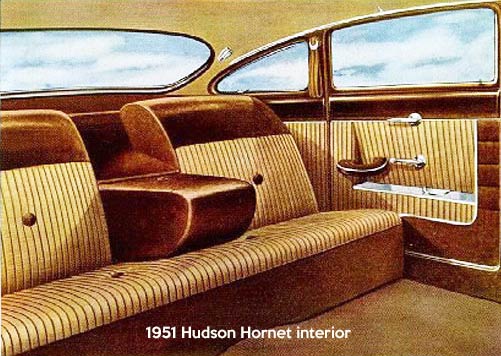

The 1951 Hornet made a big splash at the top of the line with its gold-and-chrome hood ornament, tan seats with gold stripes (or grayish-blue with blue stripes), standard pillar straps and robe hanger, tailored back-seat pockets, and clever, flashy medallions. The company advertised the upholstery as “beautiful nylon, the most durable and luxurious fabric money can buy” with an “exclusive three-dimensional weave that prevents slipping, clinging to clothes, makes it easy to clean.”

The trim was “Dura-fab,” a “wonder material” (plastic); carpet was “thick pile.” The big news for the Hornet, above all the decoration, was a high-compression, aluminum “Power-Dome” cylinder head—with a no-cost optional iron alloy head from the smaller engines for those afraid for the powerful six’s durability.

Hudson sold four engines, all but the Pacemaker’s 232 equipped with a Carter two-barrel carburetor; while most American sixes only merited a single barrel. The Pacemaker had 112 bhp, similar to the Chrysler six, while the more Chrysler-sized Commodore had 123 bhp. The straight-eight Commodore engine shared the low compression of its plebeian six-cylinder relatives, but still roughly matched Buick Super’s 263 eight-cylinder. In both body and engine, Hornet was likely ahead of Chrysler (and most or all of GM) in technology.

| 1951 | Engine | bhp (gross hp) |

|---|---|---|

| Pacemaker | 232 | 112 |

| Super Six Custom | 262 | 123 |

| Hornet | 308 | 145 |

| Chrysler Spitfire | 251 | 112 |

| Chrysler V8 | 331 | 180 |

| Buick | 263 Eight | 120-128 |

| Dodge | 230 | 103 |

| Olds | 303 V8 | 135 |

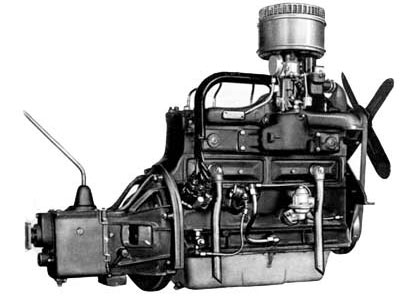

Just for the 1951 Hudson Hornet, the company made a new straight six of 308 cubic inches by boring out the 262; the stroke was 4.5 inches and the bore was 3-and-11/14 (around 3.79 inches). The standard aluminum heads were designed to provide higher compression, at 7.2:1 vs their usual 6.5:1 (the low-compression heads were a no-cost option). The engine produced 145 bhp, far above most competitive straight-eights and straight-sixes, if not quite up to the Hemi V8. Dubbed the “Miracle-H,” the conventional inline six was designed by Hudson chief engineer Harry R. Stutz and placed lower than usual in the chassis to drop the help the car’s cornering and feel. All Hudson engines took regular fuel, not premium.

The optimistically named Buick “Fireball Eight” in the Super produced up to 128 bhp; the Buick Roadmaster’s 320 Fireball generated 152 bhp, but it was a much heavier car. Even the Buick Super was a hundred pounds heavier than the Hudson; the Roadmaster had a shipping weight (lower than a curb weight) of 4,185 lb, so Hornets had little to fear from Buicks when racing down the road.

| Engine | Base Price | Length | Weight* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacemaker | 232 | $1,964 | 201.5 | 3,380 |

| Super Six Custom | 262 | $2,287 | 208.1 | 3,525 |

| Commodore Six | 262 | $2,455 | 208.1 | 3,585 |

| Hornet | 308 | $2,543 | 208.1 | 3,580 |

| Chrysler Windsor | 250 | $2,368 | 207.3 | 3,570 |

| Buick Super | 263 | $2,248 | 206.2 | 3,685 |

| Chrysler Saratoga | 331 | $2,752** | 206.5 | 3,948 |

| Olds Super 88 | 303 | $1,928 | 202 | 3,628 |

* Lightest body style; shipping weight, not curb weight (no fluids included). Figures from American Cars 1946-59.

** With $167 V8 option; required Fluid Torque Drive

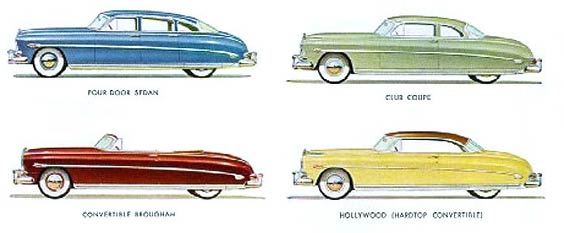

Sold as a two-door coupe, four-door sedan, convertible, and “Hollywood” hardtop coupe, the Hudson Hornet was bigger than the Chrysler Windsor but not heavier; and it was much lighter than the Buick Super. Its two-barrel carburetor and performance head made good power, and dropping the height of the engine and the driver helped with handling. It started winning NASCAR trophies; its barnstorming performance was enough to merit inclusion in the movie Cars, as a main character.

Hudsons had a synchronized mesh manual with helical gears, steering wheel shifter, and optional overdrive, with two-speed GM automatics (redubbed Supermatic) starting in 1952 at $158. For $99, Pacemaker or Super buyers could opt a semi-automatic called DriveMaster. No automatic was available on the Hornet, at least for 1952.

Shock absorbers were double-action designs in front and rear, with a front anti-sway bar. The independent front suspension had coil springs; the rear suspension used semi-elliptical leaf springs mounted at an angle, with the Hornet also carrying a rear anti-sway bar as well. Power hydraulic brakes with a reserve mechanical system on the same pedal (dubbed Triple-Safe) were standard, and faster-acting power brakes were optional. Power steering was optional. Tires were relatively large—7.10 x 15—on the entire 1951 Hudson line.

Hornet options included a radio, anti-glare (green tinted) safety glass, and heat/vent/defrost/conditioned air system. Standard features included a cowl vent and defroster vent, warning lights for oil pressure and generator, arm rests in front and rear, dual horns, lighted ignition switch, safety locks, sun visors, dome lamp, courtesy lamps on all doors, stop and tail lamps, front parking lamps, rear view mirror, assist handles, robe cord, seat pockets, and rear ashtrays.

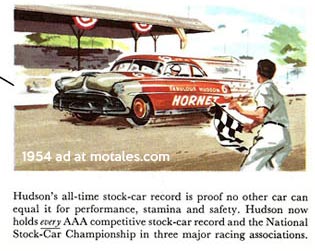

The car was racking up racing victories, facing a field of weaker sixes; the few V8s didn’t match its power and weight. The Chrysler V8 did, but aside from its heavier weight it came with Fluid Torque Drive, which was probably not suitable for racing. Marshall Teague won twelve of thirteen AAA events for 1952, claiming a 112 mph speed; when his car was torn down after the race, officials said it was 100% stock. For 1952, Hudson dominated stock car racing and took the AAA and NASCAR racing championships. (Not all of the 1951-52 races were driven in “Fabulous Hudson Hornets,” piloted by three drivers—Teague, Flock, and Thomas. The original is now in the Ypsilanti Automotive Heritage Museum.)

Hudson also won most of the 1952 and 1953 stock-car races. 1954 was still good, but not quite as good, with Hornets taking nearly half of the races. But that’s still a few years off...

The Hornet sold reasonably well for its class, with roughly 44,000 finding buyers—nearly half of the 92,859 Hudsons sold in calendar-year 1951 though they were the top of the range. It was a good position for Hudson, financially, since the Hornet likely had high margins.

For 1952, Hudson continued to give the appearance of a full line of cars from two versions of the same car. They moved the Pacemaker downmarket in appearance while raising the price to make room for the Wasp, a more luxurious Pacemaker with bumper guards that increased the length by an inch. The Wasp had the Super’s 262 engine rather than the Pacemaker’s little six, increasing power by over 10%; Wasp and Pacemaker combined merited production of just 29,362. The Hudson Hornet, meanwhile, was based on the top Commodore (Eight) trim but with the high-output six, leather window moldings, various badges and medallions, and a gold and chrome hood ornament.

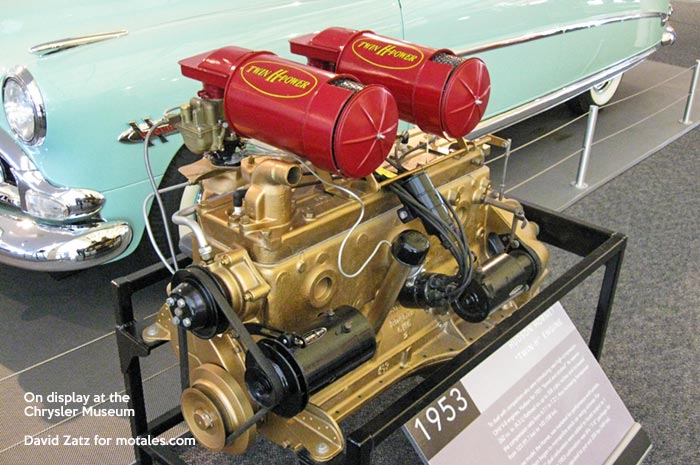

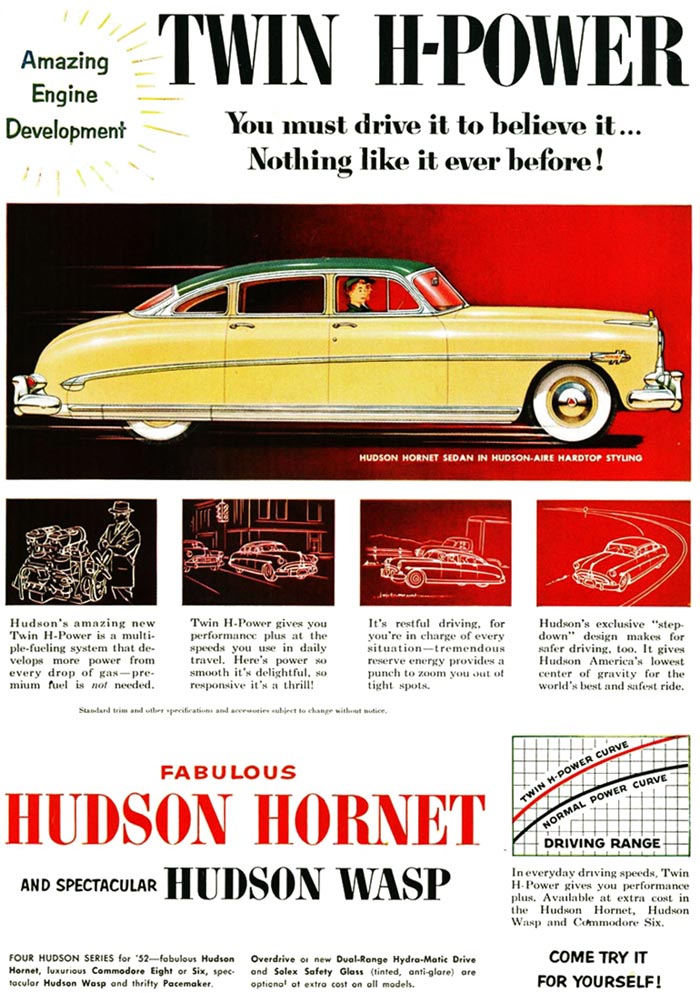

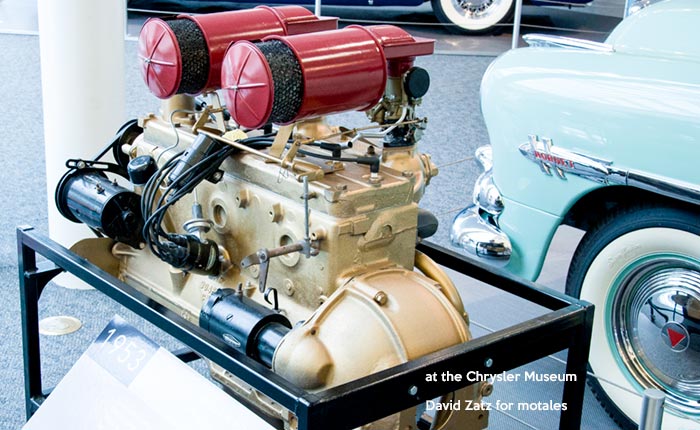

Hornet sales figures showed that power was important, and Hudson launched two new engine options to help (and fight off competing V8s). A Twin-H-Power package, with dual carburetors and intakes, joined the options list for $111; unlike many engines, it was styled for effect with two red-painted air cleaner covers and a gold-painted engine block. Professional stock car drivers could buy numerous performance parts, too—long before the Mopar people created Direct Connection. A General Motors two-speed automatic transmission was optional at $158.

A new “7X” engine aimed at stock car racers (not pictured above) generated over 200 bhp, which was V8 territory at the time; it was hand-built at the factory to exacting specifications (“blueprinted”).

The company selected the best blocks, inserted larger valves, ported and polished the intake and exhaust manifolds, and swapped in a hot cam, knurled pistons, and higher-compression heads with 8.7:1 and 9.2:1 options (the hot cam might not have appeared until 1953). They also reportedly machined the block around the valves, creating a venturi effect; used a special dual-outlet exhaust manifold; and with upgrades such as special head bolts and washers for durability. It was a racing engine, not meant for ordinary use and not sold to ordinary drivers—indeed, it was not sold in the car, but came in a crate after the car was sold. The package likely changed as time went on.

The company sold 79,117 cars for the 1952 calendar year, good for #14—but quite bad for financials, and not bound to get any better. 1949 was by far the high-water mark of the postwar Hudson, with a bump in 1951 from the Hornet and a rapid slide afterwards.

For 1953, the Hornet was updated with a new front grille and a decorative hood air scoop; it was now the sole full-sized Hornet, with the lineup consolidated to a new small car, the Wasp (replacing the Pacemaker), and the Hornet. The Commodore and Super were subsumed into the more popular Hornet, and the straight-eight was history after a year in which only 3,125 had been made.

Hornet sales still dropped to 27,208 while Hudson at a whole saw just 66,143 sales. Hudson was caught between the Chevrolet-Ford sales war—as was the entire American auto industry—and the V8 was a new status symbol. Hudson had nothing to offer but straight sixes and undersized straight eights, for the moment, even if its top straight six was more than a match for many V8s. Again, the Hornet continued to rack up victories despite other brands having increasingly powerful engines (and a nylon upholstery option).

Hudson likely made a mistake by spending its resources on engineering the new Jet, a smaller, cheaper Hudson with a 202 cubic inch version of the L-head six producing just 104 bhp from a single-barrel Carter carburetor. It took some of the allure off of the Hudson brand without contributing many sales. If they had devoted these resources to, say, a V8 engine or more updates to Hornet styling, it may have helped more than a low-margin, unpopular small car.

The 1954 Hudson series was essentially the same as in 1953, other than the edition of the “Jetliner Six,” which was essentially an upgraded Jet; the Pacemaker name had been retired in favor of the Wasp and Jet. The Hornet gained a functional air scoop, replacing the cosmetic one; the curves were squared off somewhat as the car was restyled to look more like the low-end Jet; and a one-piece curved windshield replaced the two-piece version.

The company advertised an “all new” 1954 Hornet, “even more beautiful, more luxurious, more powerful than ever” with “new Flight-Line Styling—a look of balanced, symmetrical beauty in motion” with “jet-stream rear fenders.” The interior appeared to be identical, though the body panels had been restyled to match competitors.

| Engine | 1951 bhp | 1954 bhp |

|---|---|---|

| 202 | n/a | 104/111 |

| 232 | 112 | 126/129 |

| 262 | 123 | 140-149 |

| 308 | 145 | 160/170 |

The Hornet did gain power, rising to 160 hp from the two-barrel and 170 hp with the twin single-barrels (Twin H-Power); the cast iron head, still optional, was now at 7:1 compression, with the aluminum heads still at 7.5:1. There is no indication of where the extra power output came from—perhaps carburetor, exhaust, cam, or timing changes; perhaps marketing changes. The company’s only indications were “Super Induction” and a new ignition system. They still took regular gasoline, not premium.

The big six-cylinder was now dubbed the “Hornet Championship Six” and was standard on Custom and optional on Super (the Wasp base engine was 202 cubic inches, with a 3” bore and 4.25” stroke, with optional dual carburetors). The straight-eight was history now. Despite the new Wasp, power gains, and stock car championships, Hornet sales dropped again, to 24,833—made worse by the fact that the car was responsible for around half of Hudson sales (including Hornet Specials, which had Hornet exterior touches and engines with the cheaper Super Wasp interior trim). Adding new lower-end cars hadn’t helped.

In 1954, Packard sales fell in half as the independents—and Chrysler—suffered from a hot Chevrolet-Ford price war. GM and Ford sales both rose—GM went up to 2.6 million calendar-year 1954 sales (Chevrolet was half of that) while Ford went to 1.4 million (1.1 million of which was Ford-the-brand).

| US Sales | Hudson | Nash | Packard | Chrysler* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 66,797 | 137,507 | 71,079 | 1,165,357 |

| 1954 | 35,824 | 86,129 | 34,996 | 714,347 |

| 1955 | 43,212 | 93,541 | 52,103 | 1,206,195 |

| 1956 | 11,822 | 25,271 | 28,396 | 922,043 |

| 1957 | 4,596 | 9,474 | 5,189 | 1,096,359 |

* For comparison purposes. Chrysler is entire corporation. (via Ward’s Automotive)

Midyear, Hudson merged with Nash to form American Motors Corporation to try to combine forces and survive against ever-larger competitors. The goal was for Studebaker and Packard to merge at the same time, and then for all four to become one corporation that would have a full product range—as none of them had at the time—and the ability to amortize engineering expenses across many more sales. The second merger never took place, and Hudson/Nash’s “AMC” would continue its struggle, even after buying Jeep, never being large enough to go up directly against the Big Three.

The first product change from this alliance was the sale of 1955 Hudson Metropolitans, replacing the slow-selling Jet. The Hudson Metropolitan was clearly a rebadged Nash Metropolitan, a quite small car with Rambler styling, which was not suitable for an upscale brand. It presaged the Cadillac Cimarron, a rebadged, upgraded Chevrolet Cavalier, in terms of lack of fit with an upscale brand.

The 1955 Hornet was “new from stern to stern,” but they really were not; they were not even Hudsons. The 1955 Hornet was a restyled Nash, with conservative styling; it didn’t look like a Hudson, but in fairness it was still a unibody design, marketed as “Hudson’s Double-Safe Single-Unit Car Construction.” Sold in Super and Custom form, it used Wasp styling but on a longer wheelbase. The Custom had extremely high-end interiors. The big 308 cubic inch six-cylinder engines continued from 1954, though. Buyers could now opt for a Packard 320 cid V8, producing 208 horsepower and sending it through a Packard Ultramatic transmission, ending the V8 gap. Other cars were the Wasp, also converted to a Nash but on a smaller wheelbase, with the 202 Hudson engine; and a small run of the “Hudson Rambler,” using the Nash Rambler’s name and body with very minor changes.

Hudson took a single win during the NASCAR 1955-56 seasons, out of 101 races; the new Hornet was no racing car. Chrysler took 51 wins in this season, with Dodge racking up another 11.

| 1955 Engine | bhp (gross hp) |

|---|---|

| Competition 308 | 160 |

| 308 Twin-H | 170 |

| Packard 320 | 208 |

For 1956, Hudson continued with their carryover engines in modified, renamed Nash Ramblers and Metropolitans. The Wasp name continued with a massive new grille and completely new styling, hiding its old 202 cid engine with an optional ten-bhp boost from a twin single-barrel carburetor (120 bhp standard, 130 bhp from the Twin H-Power).

| Year | Hudson Model-Year Sales | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | 83,344 | |

| 1948 | 109,497 | Unibody |

| 1949 | 137,907 | |

| 1950 | 134,219 | Pacemaker |

| 1951 | 96,847 | Hornet |

| 1952 | 78,509 | |

| 1953 | 66,797 | |

| 1954 | 34,806 | Restyling |

| 1955 | 20,522 | Rebadged Nash |

| 1956 | 11,822 | |

| 1957 | 4,596 | Final year |

The 1956 Hudson Hornet was sold on a short and long wheelbases, around seven inches apart. The old 308 was sold with a three-speed manual, manual with overdrive, or GM automatic, while the V8 was sold only with the Packard automatic. The Super and Custom trim were V8 only; Series 60 and 80 could be ordered with the V8 in conjunction with the longer wheelbase. Sedan prices ran from $2,777 (Series 60 Super Six) to $3,286 (Custom V8). The Hudson engines—308 two-barrel and 308 twin-single-barrel—both gained five horsepower. A Hudson Hornet Special arrived midyear, bearing a new 250 cubic inch AMC V8 in the shorter wheelbase, making it something of a powerhouse in the original Hornet fashion; but the Hudson Hornet was out of championship races. Fewer than 2,000 of these were made, with a price starting at $2,626.

| Year | Hornet Production |

|---|---|

| 1951 | 43,666 |

| 1952 | 35,921 |

| 1953 | 27,208 |

| 1954 | 24,833 |

| 1955 | 13,130 |

| 1956 | 6,395 |

| 1957 | 3,876 |

For 1957, Hudson gave up on the odd attempt to sell downmarket cars with an upmarket label, selling only the Hornet. They had a single engine option, the new AMC 327 V8 with dual exhausts. Only 4,108 were made—ironically, with newly developed 12-volt electrical systems.

The Hudson Hornet was an exciting car, innovative for its time. The unibody design was a definite strength, since it provided better cornering and lower weight; but it couldn’t be updated each year just by swapping body panels, a time when customers demanded a new exterior look with each new car. Hudson likely couldn’t afford the cost of updating even body-on-frame cars, in any case; they had squandered their money twice by trying to reach downmarket, and didn’t gain a V8 until they had become almost de rigeur.

Hudson stopped making cars on June 25, 1957; both the Hudson and Nash brands were replaced with the Rambler, promoted from model to marque. The new strategy paid off in sales: Rambler reached 186,373 US sales in 1958, better than Hudson and Nash, combined, had seen since 1953. Sales nearly doubled in 1959, then hit 422,273 in 1960. Had AMC completed its merger with Packard and Studebaker as planned, they may have been more successful in the 1960s and 1970s. AMC brought the Hornet nameplate back—but that’s another story—and it was long before the current Dodge Hornet.

Sources: Hudson literature; Allpar; The Standard Catalog of American Cars; Ward’s Automotive; John Rush.

Chevrolet fires across Tesla’s bows with $28,595 Bolt

Ram chassis cabs to get 25% tax on November 1

New midsize pickup to be shown next year?

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos

Tailfins Archive • MoTales on BlueSky