I’m not anti-aftermarket. I’m anti-garbage. There are great aftermarket brands out there, and a mountain of parts that never should’ve left a factory. If you want your Hellcat (or other car) to stay both fast and alive, you need to understand the difference between OE engineering and catalog parts.

When a part wears an OEM badge, it’s survived years of validation and manufacturing control. It’s not a “guess that fits.” It’s the result of engineering rigor and process discipline:

OE parts are built to survive all climates, all drivers, all abuse — for years

Not every aftermarket supplier is bad, but most operate under price and speed pressure, not validation rigor. These are common problems:

These problems can effect OE parts, too, but when they do, automakers find them and fix the processes, working with the supplier.

Parts that fit perfectly until they don’t — and slowly bleed performance, efficiency, or reliability in ways you can’t see on day one.

If a company can show you data — test curves, materials, certifications — they’re worth your money. If they show you anodizing and influencers, they’re not.

Extra horsepower hides inefficiency until heat, friction, or electrical noise exposes it. Cheap components increase losses through drag, distortion, or poor signal fidelity.

That’s why a well-engineered 700 hp car often outruns an 850 hp parts-bin special.

OE parts are boring on purpose. They’ve already survived the testing that ensures you don’t.

Aftermarket parts can be brilliant — or a ticking time bomb. The difference is validation, process control, and accountability, not anodized colors or hype.

If a brand can hand you a DVP&R report and material certs, run it with confidence. If all they hand you is a discount code, let someone else do the beta testing.

The goal isn’t to spend more. The goal is to fail less.

That’s how you go fast for a long time.

In this section, an editor summarized Mark’s replies to posts on the Allpar forums.

An Allpar member asked about failures in OEM parts, such as the Pentastar’s cams for certain years.

The “cheapening” you’re referring to isn’t always a drop in quality; it’s optimization creep.

OEMs (especially under Stellantis) are constantly balancing emissions regulations, warranty data, and global cost targets. You’ll see spec changes (like camshaft material or heat-treat variations on the Pentastar), but those come from data-driven durability models, not cost-cutting roulette.

I’ve worked on the OEM side, been through full part validation and design reviews, and later worked for a major automotive retailer. I can’t share everything, but I can tell you this — the difference between a validated OE part and a typical aftermarket one is night and day. OEM components go through DVP&R testing, thermal and vibration cycling, and bench durability hours that aftermarket suppliers often skip entirely.

When people say “aftermarket is just as good,” they’re usually talking about appearance, not endurance. The majority of the low-cost parts flooding the market are built to pass the sale, not to survive the lifecycle.

So yes, OEMs “optimize,” but they don’t compromise. There’s a difference between trimming cost and gutting engineering. The former is finance. The latter is malpractice....

Some Chrysler/Jeep parts absolutely had documented issues, and the record shows it. Example: Jeep addressed the JL steering shimmy with Customer Satisfaction Notification V41 to replace the steering damper on 2018–2019 Wranglers, and followed with later updates. They also issued TSB 18-092-19 to change PCM behavior when the ESS auxiliary battery degrades so owners don’t get stranded. Early LX (300/Charger/Magnum) cars had front-suspension alignment/NVH bulletins and spec revisions. Those aren’t internet rumors—they’re official TSBs/CSNs with revised parts.

Where the blanket “OEM = cost-cut garbage” take falls down is that OEMs have to remediate at scale—they publish TSBs, extend coverage, and supersede components—while aftermarket doesn’t validate at vehicle-system level. Also, during the same timeframe you’re pointing to, FCA/Jeep’s measured initial quality improved in independent J.D. Power data. In short: yes, a few parts/programs needed fixes; no, that doesn’t make “many OEM parts crap.” Evaluate the specific component and look for official countermeasure history and test data, not anecdotes....

The same APQP, PPAP, and DVP&R disciplines I talked about are still in place; they’re even tighter now, because Stellantis digitized supplier traceability. What changed isn’t the testing, it’s the economics and distribution behavior around it.

On a personal note, the “bell curve” mindset and sigma discussion is the logic underpinning Six Sigma capability and reliability B-life modeling (B10, B50, etc.). This is part of the math behind the warranty life conversation. I’m a Quality Master Black Belt, so I live in this world daily. Tightening sigma to manage cost happens, but not in the “designed to fail at 61,001 miles” sense. OEMs statistically balance Cp/Cpk, field failure probability, and warranty accrual exposure under IATF 16949. If failures trend toward the edge of that bell curve (like some Pentastar cam issues did), the system detects it through warranty analytics, triggers a DVP&R revalidation or TSB, and adjusts the process window. It’s a control loop, not a conspiracy.

(If you’re enjoying this type of analysis, I’d seriously recommend you get into Lean Six Sigma training — even at the Green Belt level. It’ll give you the frameworks to connect data patterns to root causes, design tolerances, and cost-of-quality strategy. It’s addictive once you realize how much hidden variation you can uncover with the right statistical tools.)

The math behind automotive reliability is real, but it’s meant to prevent failures, not schedule them.

When the warranty process fails, it makes the whole OE system look bad, even when the part itself isn’t the problem. I get it — if you pay for the real stuff and the company won’t stand behind it, that leaves a bad taste.

“Lifetime warranties” are financial bets, not engineering promises. The companies know the odds most people won’t bother claiming them. That doesn’t mean the part’s better, just that they priced in the risk.

OE validation still runs deeper than any warranty can cover. Every batch is tested, verified, and traceable — but that control doesn’t always extend to how the claim’s handled at the counter. That’s where the disconnect happens.

Aftermarket pricing looks better because they’re not carrying the overhead of full-system validation or global warranty exposure. Once you step back from the retail noise and look at process control, OE still plays in a different league.

Cost and access have gone the wrong way, but the engineering backbone that keeps a Hellcat or Hemi alive under real abuse hasn’t gone anywhere.

Once a platform ages out of production (usually 10 years after sunset), the OE part isn’t really “OE” anymore. What you’re seeing with Motorcraft and others is the same pattern across the industry: legacy parts are handed off to suppliers for low-volume contract runs, often with less validation and weaker supply oversight.

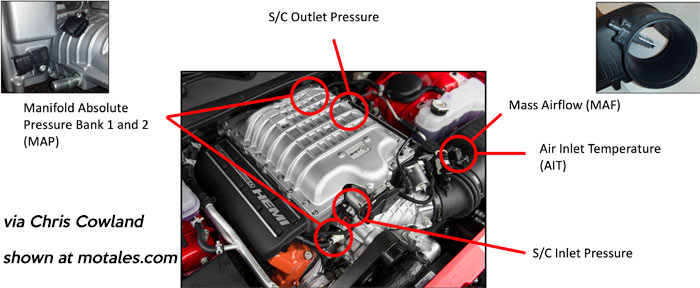

It’s good to chase down original parts where possible, especially for sensors and ignition components. Those were built around tighter calibration tolerances for the original cars, and the cheap replacements almost never hit the same signal accuracy or heat resistance. It’s not that OE standards disappeared; it’s that they’ve been diluted in the aftermarket-style supply chain that services legacy vehicles. That’s exactly why the article focuses on validation and traceability — because even a “genuine” label today doesn’t always mean the same discipline behind it.

Guest insights at Motales: sales, parts, factory

Updated: 300,000-Dart re-recall and many Ford callbacks

Barra mitigates tariffs, sees big GM profits

Copyright © 2021-2025 Zatz LLC • Chrysler / Mopar car stories and history.

YouTube • Editorial Guidelines • Videos